“We’re So F*cked”: Notes on American Fascism

From the Series: American Fascism

From the Series: American Fascism

Americans are sensing that the end of democracy is near. Some let out a fatigued sigh of relief following the 2020 presidential election. Others saw the election as another sign of imminent doom. They were convinced that its reported outcome was a lie. Their candidate, Donald Trump, had actually won.

Tens of thousands of people came from across the country to the “Stop the Steal” or “Save America” rally in Washington, D.C., on January 6, 2021, to prevent this theft of the presidency. What many of us perceive as an attempted coup that day was a brush with . . . What, exactly? Fascism? Authoritarianism? Populism? Wendy Brown (2019, 2) notes, “We . . . have trouble with the naming.” The marchers that day also expressed concern about the dangers posed by authoritarian or totalitarian government.

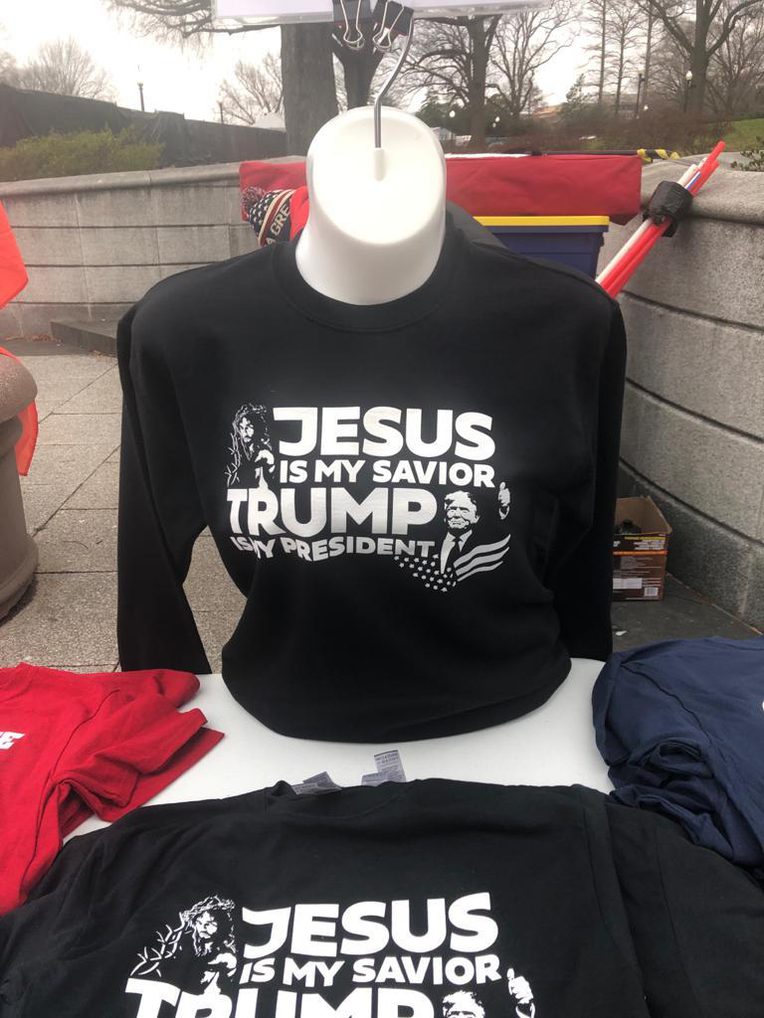

The rally that preceded the Capitol’s invasion was overwhelmingly optimistic, celebratory, and even joyful.1 It resembled an enormous tailgate party—cheering for your side and insulting your rivals. In addition to the banners and flags, people came with their children and pets, toting cases of beer and purchasing snacks from food trucks. They were certain that their savior would triumph and save their democracy. This savior was characterized sometimes as Jesus, but simultaneously as Trump, depicted in shifting imaginary forms as tireless warrior, plucky underdog prizefighter, comic book superhero, or as God’s “Chosen One.” Together, they would (re)consecrate the nation to God.

The atmosphere of the rally was remarkably orderly. Marchers were jovial and well-behaved as they made their way toward the site where the president was to speak. It was not a raucous or bawdy outburst. People walked on the sidewalks and crossed at the crosswalks despite the empty streets, closed by police barricades. Trios of D.C. national guard troops were posted at strategic corners throughout the center city. One white guardsman told us that being on duty “these last two days has been much better than during the summer [when Black Lives Matter protests erupted around the country over the police murder of George Floyd] because people are calm and well-behaved. People aren’t calling me a fascist or throwing rocks or bottles full of urine at us. Besides,” he said, “these people are on our side.”

The marchers’ largely uniform banners and flags had been mass-produced with the same repeated sets of colors, images, and slogans. We saw recycled campaign paraphernalia from the 2016 and 2020 elections in red, white, and blue, but also fresh taunting refrains, such as “F*ck Your Feelings,” and “Make Liberals Cry Again,” along with plenty of “Blue Lives Matter” banners. The marchers enacted solidarity, shouting out to each other, “Where are you from?” After hearing the reply—Arizona, Pennsylvania, Florida, Hawaii—they responded, “Thank you for coming!” When we asked why they’d made the long trip, people told us the stakes couldn’t be higher.

One woman asked us where we were from. “North Carolina,” we said. “I am so grateful,” she replied, tears welling up in her eyes. Her family had come from Vietnam and she wanted her children to have the freedoms America promised. “This is not Russia or China,” she said; this event was preserving American democracy. The rally’s large attendance gave her hope. Later we encountered a small group of Chinese people holding posters depicting Joe Biden as a marionette with Xi Jingping controlling the strings. Another group carried banners announcing that Trump was charged by God to save the country from Chinese manipulation of the 2020 election.

God was, indeed, omnipresent. When insurrectionists breached the Senate chamber that afternoon, they bowed their heads in prayer, thanking God for allowing them to “send a message to all the tyrants, the communists, and the globalists that this nation is not theirs, that we will not allow . . . the American way . . . to go down . . . Thank you for filling this chamber with patriots that love you and that love Christ . . . Thank you for allowing the United States of America to be reborn.” When the Senate reconvened later that night they repeated the sentiment: “You have strengthened our resolve to protect and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, domestic as well as foreign. . . . Thank you for what you have blessed our lawmakers to accomplish in spite of threats to liberty.”

Hannah Arendt (1964, 52) noted Nazi ideology’s invocation of a broad sense of promise. Then, it was the battle for the destiny of the German people. Now, it is the battle for the destiny of the American people. Perhaps we have witnessed “something like . . . a pseudo-insurgency—with the caveat that a pseudo-insurgency was in many ways what the murderous fascism of Europe’s interwar period embodied” (Toscano 2017). As the Capitol building was being breached by protestors, one woman watching from a nearby plaza told us, “We the People are in the House.” But doubts remained; another woman was sure that such apparently lawless behavior must have been carried out by infiltrators.

Despite the sense of solidarity and joyful anticipation of a reborn democracy, the rally was a site of suspicion. Were deep state agents there? Were Antifa activists pretending to be Trump supporters? Upon our arrival the evening prior to the rally, we were greeted with a wary tone and a glance at our masks that suggested we were being vetted. “Welcome to the party!” a woman shouted to us, gauging our reaction.

Many people live with a pervasive sense of danger, suspicion, and precarity in America’s white Christian patriarchy. It is the way impoverished and oppressed peoples often experience the world. But such affect—regardless of real or imagined threat—is not limited to the marginalized. It is carefully engineered and reinforced by a media ecology that constantly reinvigorates the threats. It is at the same time the lived experience of a neoliberal capitalism in which the only value is competition, and “nation, family, property and the traditions reproducing . . . privilege . . . are reduced to affective remains” (Brown 2019, 20, 187–88). There is little room for anything but a constant sense of potential loss. Lauren Berlant (2011, 192) suggests that this “spreading precarity provides the dominant structure and experience of the present moment, cutting across class and localities” and leaving people “no guarantees that the life one intends can or will be built.” “Where are we?” Wendy Brown asked. Where are we, now that promised futures have been undermined or indefinitely postponed?

On the morning of January 7, after the huge celebratory rally and the smaller violent insurrection had both failed, more promises left unfulfilled, we asked one elderly man, packing up his pickup truck for the long drive back to Florida, if he planned to return on January 20, when Joe Biden was scheduled to be inaugurated. There had been rumors that people would, once again, try to reinstate their president/redeemer. The man appeared despondent, his eyes filled with grief. “What for?” he asked. “It’s over.” A young woman sitting on the curb waiting for a ride also seemed defeated: “We’re so f*cked!” she said.

Indeed, it’s true. We. Are. All. So. F*cked.

1. For a more detailed analysis of the events of January 6, see our

forthcoming article (Dalsheim and Starrett 2021).

Arendt, Hannah. 1964. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Penguin.

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Brown, Wendy. 2019. In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Antidemocratic Politics in the West. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dalsheim, Joyce, and Gregory Starrett. 2021. “Everything Possible and Nothing True: Notes on the Capitol Insurrection.” Anthropology Today 37, no. 2: 26–30.

Toscano, Alberto. 2017. “Notes on Late Fascism.” Historical Materialism (blog), April 2.