Woman, Art, Freedom

From the Series: Woman, Life, Freedom

From the Series: Woman, Life, Freedom

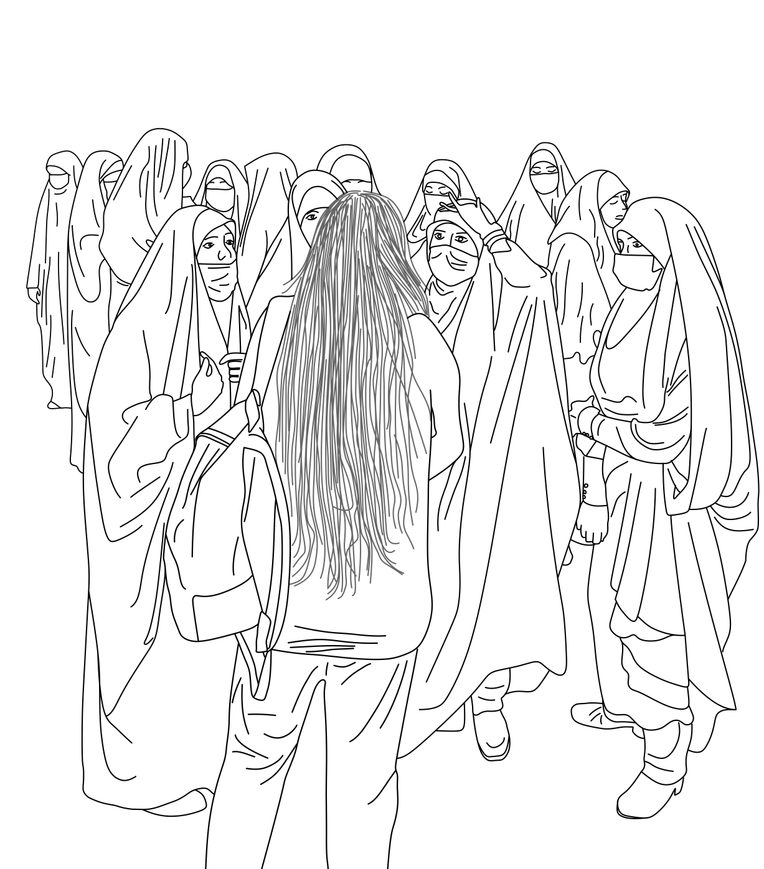

Following the tragic murder of Mahsa Zhina Amini in September 2022, Iranian women took to the streets in large numbers to protest. Whether from an art background or not, the actions of these groups bordered on performance, such as unveiled women confronting state authorities. Women’s courageous presence in public spaces has been a crucial aspect of this uprising, with many instances of women’s political activism on the streets taking on characteristics of art production. The spirited political activism of women, artfully embodied through performative gestures, burgeoned into the seminal force of the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising.[1]

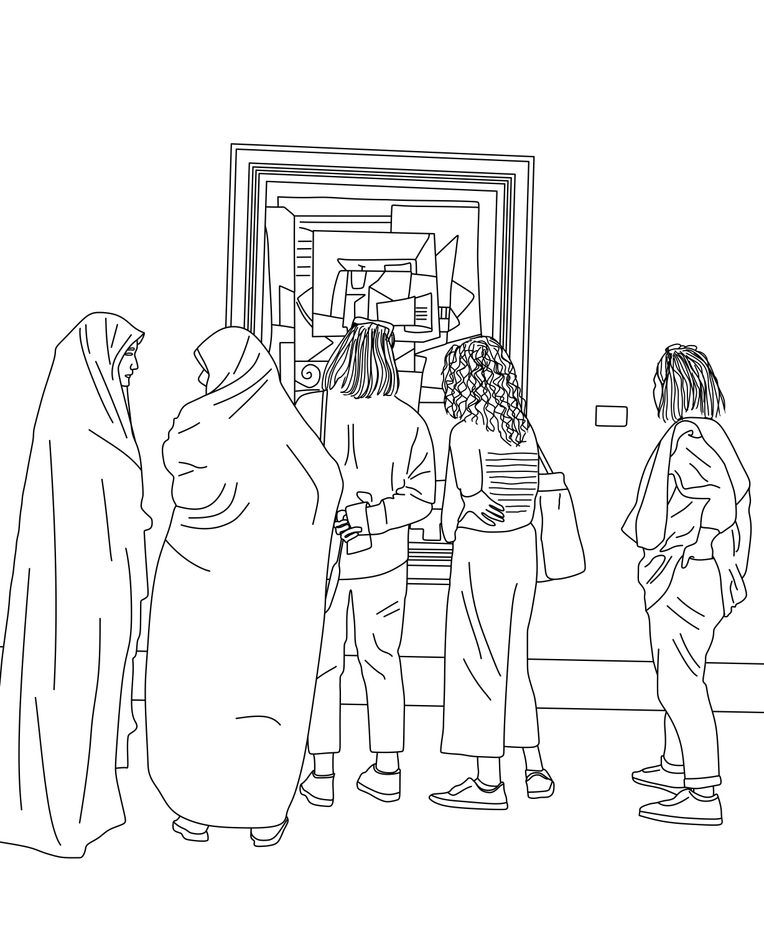

Even months after the peak of the protests, women continue to venture into public spaces and state institutions such as museums without wearing the veil.

The title of this essay, which substitutes the word “art” for “life,” encapsulates both the spirit of the protests and the politically-conscious approach to art that has developed in Iran in the decades leading to the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising. Many Iranian artists identify with the belief expressed by the renowned theatre director Peter Brook that art is a medium to authentically depict the intricacies and dynamism of human existence. Having contributed to the Shiraz Arts Festivals during the twilight of the Pahlavi monarchy, Brook especially regarded theatre and performance as avenues for articulating and enriching life. Similarly, post-revolutionary Iranian experimental theatre groups like Av, use their performances as therapeutic tools to provide both actors and audiences with a sense of bodily relief from the routinized violence of sociopolitical conditions. There is, indeed, a close relationship between art and life in Iran.

For over three decades, Iranian women artists and, by extension, women activists as artists have engaged in public art activism, creating moments of rupture in everyday life without declaring an overt political stance. These artists have used guerilla-style tactics such as painting graffiti, playful wandering, and occupying empty urban spaces to assert their right to the city and to challenge strict urban regulations. Such innovative practices in busy urban areas are more challenging for women artists and activists than for their male counterparts. A full analysis of public protest art by women is beyond the scope of this essay. Here I sample a few representative works by women artists who have questioned the limitations of public life for women and reclaimed the streets through their creative and courageous interventions. These artists challenge conventions that are tangled with four decades of subordination and exclusion of women, without necessarily relying on local or international infrastructure of museums and galleries. Their performances bear resemblance to acts of protest, which similarly arise in response to systemic oppression and constitute a civil action both in their inception and implementation.

After the Iran–Iraq War, discussions began to emerge regarding women’s issues, albeit encapsulated within the narrow Islamic framework of the state. Many participants in this debate belonged to the conservative milieu of the state. Artists, in parallel, adopted a careful approach, seeking to enhance the lives of women while navigating the parameters set by the authorities. In the 1990s, forms of art began to surface that tactfully blamed customary practices and archetypal character types of Iranian society, instead of openly denouncing the entire system. For instance, in the film “Two Women,” director Tahmineh Milani featured cultural traditions that imposed limitations on women within the family and society more generally. In the other direction, performance artists leveraged cultural traditions and iconographies as resources for women to assert their place in Iranian society.

In 2003, artist Jinoos Taghizadeh installed “Oblation (Nazr)” in front of the Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque in Isfahan, without seeking any authorization. The installation featured a ten-meter tarpaulin sheet covered in pears, which resembled the curves of a female body, and passersby were invited to take them for free, like a religious offering. The installation was intended to highlight the absence of women’s voices in public spaces, particularly at religious sites. Despite being questioned by authorities, Taghizadeh did not explain her intentions, stating that “one should never speak of the reasons for which the pledge or oblation or nazr is done.” The work was both a religious act and an interventionist gesture that questioned the limits of public life for women. The installation had a short life, remaining faithful to time-based art's ontology, whose only life is in the present and for impact on the ground (Karimi 2022, 157–159).

During Mohammad Khatami's presidency (1997–2005) and what is known as the reformist period, women experienced greater social freedom. In 2007, the One Million Signatures Campaign emerged as a prominent movement aimed at eliminating discriminatory gender laws in Iran. As Khatami’s tenure drew to a close, the campaign confronted severe clampdowns. Numerous activists were interrogated and some arrested and jailed. Nevertheless, the campaign played an instrumental role in elevating awareness about the inadequacies of Iranian gender laws, both within the country and on the global stage.

The Green Movement of 2009, then the most significant popular uprising since the Islamic Revolution, had noticeable impact on the work of many visual artists, particularly women. Among them was Mehraneh Atashi, who while participating in the protests took a series of self-portraits (khod negareh) using a lens-less Holga 120 camera with a pinhole aperture. The resulting photographs had an unpredictable quality and a characteristically dreamy, vintage appearance. The photos showcased her participation in the protests, but also her discomfort as a forcedly veiled female subject (both photographer and the photographed) as she confronts the shock of being exposed in a chaotic space (Dibazar 2020, 29–30). Atashi’s creative documentation of the demonstrations did not go unnoticed; she was arrested and interrogated about her work and activism. Interrogations did not prevent artists from supressing their public presence.

In 2011, a group of women dressed in bright red garments and shoes stood still and remained silent for an hour between 5 to 6 pm in Tehran’s Ferdowsi Square. This performance was a tribute to a certain “lady in red” who allegedly awaited her lover at the square in the 1970s. Despite facing harassment and questioning from state authorities and some bystanders, the women continued their daily demonstration for three months. This public display of love was a bold act of a kind that had never been seen since the Islamic Revolution (Karimi 2022, 191–195).

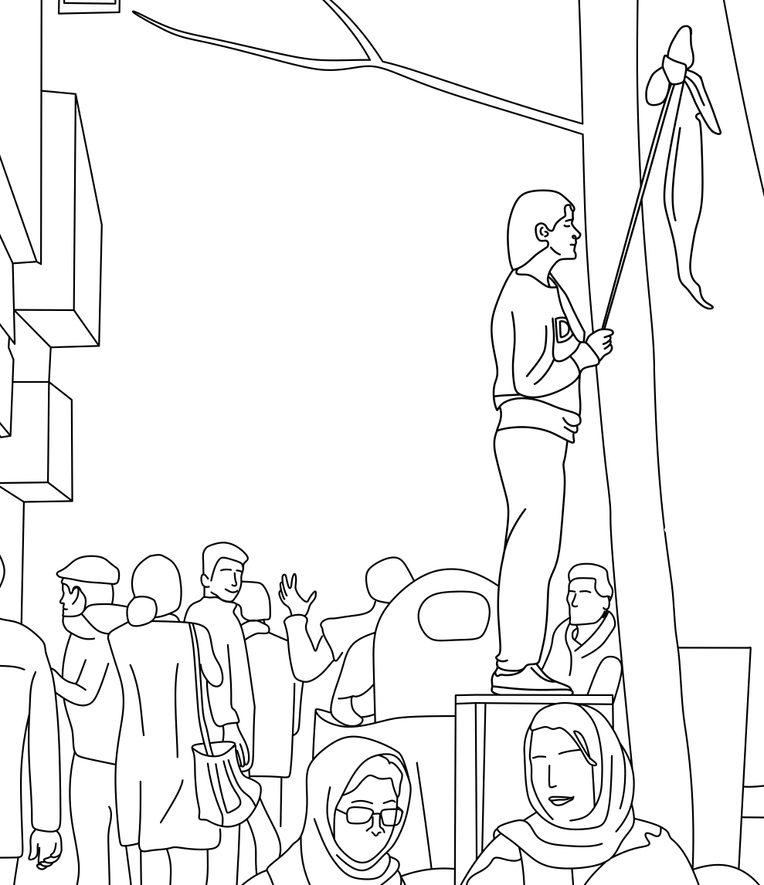

Six years later in 2017, a woman in Enghelab (“Revolution”) Street stood on a utility box above a busy sidewalk and waved her headscarf like a flag tied to a stick. She was immediately arrested and given a prison sentence. The images of her act and her arrest proliferated across social media platforms. Her assertive pose became a symbol of women’s resilience, inspiring many other such performances and artistic interventions. Performative acts and protest gestures by non-artists possess a remarkable potential for dissent, while also holding the power to project artistic qualities, whether in a direct or indirect manner. Their impact is not only significant, but also multifaceted, serving as a means of both political resistance and performative and artistic expression.

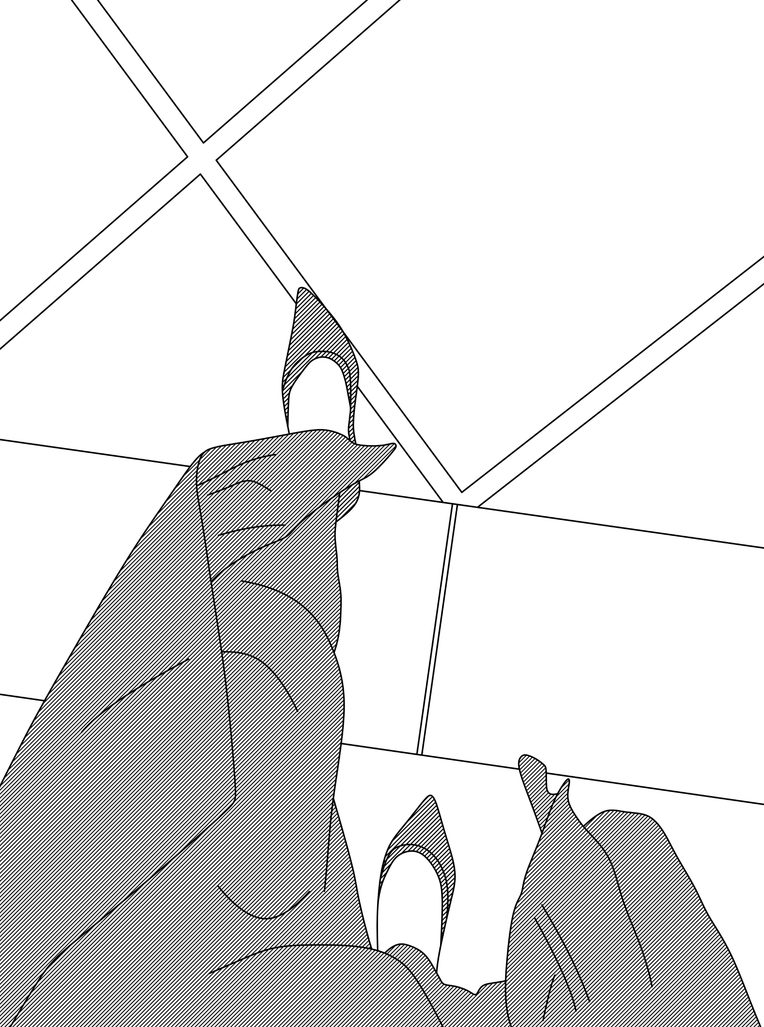

In parallel to this unveiling event, professional artists engaged in other daring street performances. Nastaran Safaie created a video titled “High Heels” (a.k.a. “Pavement Narratives”), in which she walked the entire length of Vali Asr, a central street in Tehran, in high heels, capturing verbal harassments by all kinds of agents on a hidden GoPro camera. State authorities who appeared to be operating covertly later interrogated the prominent gallery in Tehran that courageously displayed the video footage. However, the female gallerist skillfully avoided cancellation of the exhibition by justifying it as a means to create a safer public space for women, in line with Islamic values (Karimi 2022, 179–182).

In the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, women have largely appeared anonymously. Anonymity is not just for protection, which it does not guarantee anyway. Many women remove their identities from the story their creative acts of protest to amplify the political message of their work. In commemoration of the 2015 terrorist attack on their Paris offices, Charlie Hebdo published cartoons of Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, on January 4, 2023. For Charlie Hebdo, whose depiction of Islam and Muslims often risks exacerbating racial and civilizational tropes of European society, this was an act of solidarity with Iranian protesters who were being charged with “enmity against God and the Islamic state.” Following the publication, the Iranian regime issued a warning about the “indecent and insulting” nature of the cartoons. On January 8th, a prominent commercial billboard above Tehran’s bustling Hemmat Expressway exhibited a Charlie Hebdo-inspired parody. The image depicted Khamenei wearing a turban fashioned from nooses, accompanied by the caption, “Water the tree of the revolution with my blood.” The installation process was captured on video and shared widely on social media, featuring a masked young woman perched atop the unsteady metal pole from which the banner was suspended. The footage showed her striking a pose with arms raised and flashing the “V” sign for victory.[2]

Other protesters engaged in similarly controversial actions such as physically striking and removing turbans from clergymen or setting Islamic veils ablaze. While some condemn these actions as unmeasured and impulsive, they can also be seen as expressions of empowerment and rejections of the patriarchal and clerical establishment. As cultural theorist Sara Ahmed writes, expressions of rage are sometimes one of the “conditions of possibility for feminist anger to get a just hearing” (2014, 177). Repeatedly performing such daring actions could have a long-lasting impact by igniting the collective imagination and inspiring alternative visions of ways to live.

For decades, Iranian artists have consistently expressed their defiance through corporal performances or by portraying images of resistance and civil disobedience through stylized forms and other artistic expressions. This highlights the reciprocal relationship between art and activism, as they mutually complement and enhance one another, contributing not only to the social and political fabric of Iranian society but also to expanding the existential horizons of gendered identity across different cultures. The transformative impact of this feminist movement, which is largely manifested through artistic and performative acts, has not only reshaped the status of women in Iranian society but also redefined the essence of masculinity. Numerous male activists and artists have demonstrated solidarity with women by wearing veils in public. Despite the regime’s attempts to suppress the protests and despite a temporary lull in protest activity, the movement is far from over. As demonstrated in this essay, women's performances in Iran over the past thirty years have exhibited a steady increase in the intensity of their resistance to the system. These demonstrations mark a notable shift in attitudes, reflecting a mounting demand for women’s liberation.

Ahmed, Sara. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. New York: Routledge.

Dibazar, Pedram. 2020. Urban and Visual Culture in Contemporary Iran: Nonvisibility and the Politics of Everyday Presence (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2020), 29-30.

Karimi, Pamela. 2022. Alternative Iran: Contemporary Art and Critical Spatial Practice (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2022), 157-159.

Karimi, Pamela. Forthcoming 2023. “Art of Protest in Five Acts.” Iranian Studies.