This post builds on the research article “Writing the Implosion: Teaching the World One Thing at a Time,” which was published in the May 2014 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnote

Cultural Anthropology has published a number of essays exploring unexpected connections, including Eva Hayward's "Fingereyes: Impressions of Cup Coral" (2010); Alex M. Nading's "Dengue Mosquitoes are Single Monthers: Biopolitics Meets Ecological Aesthetics in Nicaraguan Community Health Work" (2012); and Kregg Hetherington's "Beans before the Law: Knowledge Practices, Responsibility, and the Paraguayan Soy Boom" (2013). The journal also published a book review by Tony C. Brown of Donna Haraway's When Species Meet (2009).

About the Author

Joseph Dumit is Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Davis. He is a self-described “anthropologist of passions, brains, games, bodies, drugs, and facts.” His research and teaching seek to examine how individuals think and speak about the world(s) that they inhabit. His research spans multiple fields, including the pharmaceuticals, cyborgs, new technologies, and computer gaming. He is Director of Science and Technology Studies and stands on the executive committee of the Performance Studies Graduate Group.

Publications

Professor Dumit’s new book, Drugs for Life: How Pharmaceutical Companies Define Our Health (Duke University Press, 2012), is concerned with pharmaceutical marketing and clinical trials, and it was featured on BBC Radio 4′s Thinking Allowed. He has previously written about neuroscientists making brain images in Picturing Personhood: Brain Scans and Biomedical Identity (Princeton University Press, 2004), and has co-edited several works including Cyborgs & Citadels: Anthropological Interventions in Emerging Sciences and Technologies (SAR Press, 1998), Cyborg Babies: From Techno-Sex to Techno-Tots (Routledge, 1998), and Biomedicine as Culture: Instrumental Practices, Technoscientific Knowledge, and New Modes of Life (Routledge, 2007). For ten years, he served as editor of the journal Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry.

2006. “Illnesses You Have to Fight to Get: Facts as Forces in Uncertain, Emergent Illnesses.” Social Sciences and Medicine 62, no. 3: 577–90.

2003. “Is It Me or My Brain? Depression and Neuroscientific Facts.” Journal of Medical Humanities 24, no. 1–2: 35–47.

1999. “Objective Brains, Prejudicial Images.” Science in Context 12, no. 1: 173–201.

1995. With Gary Lee Downey and Sarah Williams. “Cyborg Anthropology.” Cultural Anthropology 10, no. 2: 264–69.

On-going Research Projects

Dumit describes his on-going work as involving multiple terrains and areas of study, including:

Gaming Studies

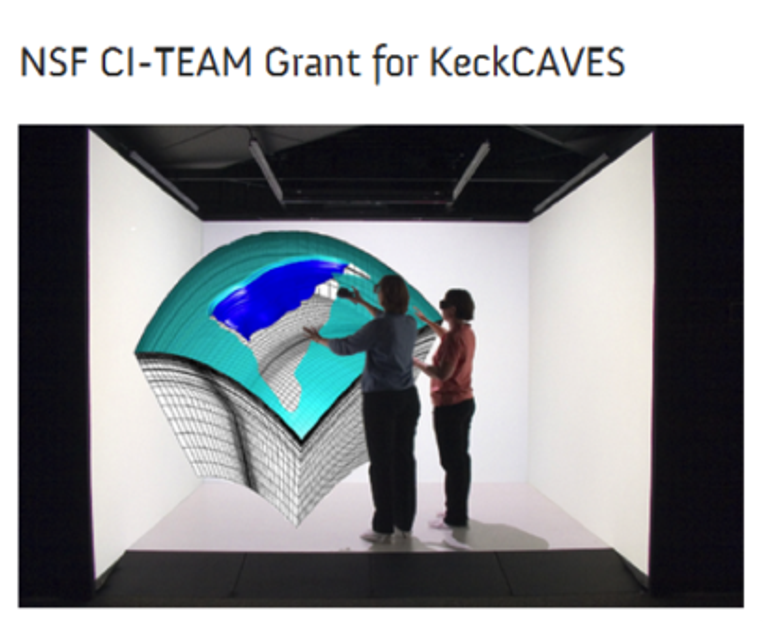

With Colin Milburn, Kriss Ravetto, and others, Dumit founded the Humanities Innovation Lab through the Davis Humanities Institute, and also funded by IMMERSe, Mellon, and a new Interdisciplinary Frontiers grant at UC Davis. The team of researchers seeks to study gaming and developing games and interfaces.

Crazy Computers and Logical Neuroses

Dumit writes that the early period of computing (1940–1960) is fascinating for “how many people then felt that computers were logical and therefore irrational, that is, because they did exactly what they were told and didn’t know if they were going in endless loops, they were ideal to model the craziness of humans, our emotions, neuroses, psychoses, and politics.” He is particularly interested in “diagrammatic thinking” and he is presently working on a history of flow charts.

Anatomies

Anatomy (including physiology) is a diverse field, which includes many different kinds of medical and biomedical systems. Dumit is particularly interested in exploring various different strategies and approaches to understanding human anatomy.

Excerpts

On “Cyborg Anthropology”

(From the paper delievered at the 1992 AAA conference by Gary L. Downey, Joseph Dumit, and Sarah Williams)

We view cyborg anthropology both as an activity of theorizing and as a vehicle for enhancing the participation of cultural anthropologists in contemporary societies. Cyborg anthropology brings the cultural anthropology of science and technology into conversation with established activities in science and technology studies (STS) and feminist studies of science, technology, and medicine. As a theorizing activity, it takes the relations among knowledge production, technological production, and subject production to be a crucial area of anthropological research. Although the cyborg image originated in space research and science fiction to refer to forms of life that are part human and part machine, it is by no means confined to the world of high technology. Rather, cyborg anthropology calls attention more generally to the cultural production of human distinctiveness by examining ethnographically the boundaries between humans and machines and our visions of the differences that constitute these boundaries. As a participatory activity, it empowers anthropology to be culturally reflective regarding its presence in the practices of science and technology and to imagine how these practices might be otherwise.

On the “Digital Form”

(From the introduction to a Curated Collection edited by Lisa Poggiali and Jeremy Trombley)

Some of the questions that frame this conversation on the digital form are: How do digital technology’s material components (e.g., hardware, software, source code, binary code, network protocols) and properties (e.g., mutability, interactivity, erasability) shape the contours of ethics, politics and sociality today? What are the competing epistemologies and ideologies that undergird digital technology’s production, and how are subjectivities made and remade in relation to them? All of the articles [in this issue] gesture towards answers to these questions, which lie at the heart of an investigation into the significance of the digital in our contemporary moment.

On “Multi-Species Anthropology”

(From the introduction to the special issue of Cultural Anthropology edited Eben Kirksey and Stefan Helmreich)

“Becomings”—new kinds of relations emerging from nonhierarchical alliances, symbiotic attachments, and the mingling of creative agents (cf. Deleuze and Guattari 1987:241–242)—abound in this chronicle of the emergence of multispecies ethnography, and in the essays in this collection. “The idea of becoming transforms types into events, objects into actions,” writes Celia Lowe. . . . Multispecies ethnography has emerged with the activity of a swarm, a network with no center to dictate order, populated by “a multitude of different creative agents” (Hardt and Negri 2005:92). The Multispecies Salon — a series of panels, round tables, and events in art galleries held at the annual meetings of the American Anthropological Association (in 2006 and 2008) — was one place, among many others, where this swarm alighted.