This post builds on the research article “"Your eyes are green like dollars": Counterfeit Cash, National Substance, and Currency Apartheid in 1990s Russia,” which was published in the February 1998 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Overview

In “‘Your Eyes are Green Like Dollars’,” Alaina Lemon analyzes Russians’ relationships with currency in the 1990s. She demonstrates how discourses surrounding money reveal anxieties about the relationship between value and surface appearances, how they index evaluations of national substance, and how social identities produce and are produced by currency practices. Going beyond conventional analyses which presuppose the solely abstract nature of money’s value, Lemon argues that cash simultaneously abstracts some values while solidifying others. She begins by discussing the ways in which Russians sought to read “real” value into the aesthetic qualities of cash in a context where the relationship between surface appearances and value was constantly being scrutinized. This led to the creation of a folk science for authenticating real and fake bills; at the same time, however, this created a situation in which the aesthetic qualities of bills were extended as tropes for the qualities associated with the currency itself: thus, the historically stable US currency and the continuity of its green color through time meant that the color green itself became associated with stability. On the other hand, the frequently changing size and color of ruble banknotes was read as an index of its instability.

The relationship between aesthetics and value was not merely drawn out as the ahistorical properties of currencies. Lemon demonstrates that at the same time, and in the context of Russia’s increasing dollarization of the 1990s alongside the ruble’s devaluation, discourses on rubles and dollars also interpolated them into Russian imaginaries of national substances; that is, into the fading sense of national grandeur, and the Soviet Union’s displacement by the US. Whereas dollars could be dangerous as potential counterfeits (and thus represented a kind of foreign threat), that the ruble should be replaced by it was nevertheless also seen as appropriate, given that it was at least the currency of the other superpower.

This distinction between rubles and dollars also produced different kinds of social spaces in what was termed “currency apartheid” in the media at the time. Foreigners and wealthy Russians were able to access the spaces associated with dollars, while the poor were resigned to those linked to rubles. Beginning in 1993, the decrease in restrictions on access to US dollars decreased the division between these spaces; this coincided, however, with the ruble’s inflation which brought with it increased sense of instability as the dollar’s buying-power in relationship to foreign goods remained relatively unchanged while the ruble’s buying-power of domestic goods was in a constant state of flux.

Finally, the ways in which this split between dollars and rubles was mediated also pertains to the manner in which currency and identity were interrelated. On the one hand, deploying a dollar bill could be viewed as incriminating (by pointing to foreign ties) while simultaneously being empowering for one to display, since it tried to impart credibility to claims of powerful connections. At the same time, Russians’ ability to deploy these monetary signs to perform particular social identities was caught up in existing, racialized categories of difference and exclusion. Romani would have more difficulty using dollars without those banknotes being suspected as counterfeits than other, lighter skinned Russians. Thus, Lemon suggests, there is a dialectic in the performativity of money: it can be mobilized to perform particular social identities, but at the same time, other kinds of social identity come to influence perceptions of the money’s authenticity.

About the Author

Alaina Lemon is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Michigan. She is a socio-cultural and linguistic anthropologist who works in Russia and the Former Soviet Union. Her theoretical concerns lie mainly with ways to understand how worries about communication relate to struggles over political change and social hierarchy. She has conducted research in theaters and on film sets (both as observer and performer), in street markets and kitchens, in archives and with media. Methodologically, Lemon's ethnographic writing situates interactions within broader social institutions and relations, and connects them to trajectories of longer duration. Her current project investigates a cluster of anxieties and hopes about “contact” and “compassion,” “mental influence” and “mind control,” tracking threads of practice across Cold War telepathy science, recent theatrical and documentary pedagogy and production, and ways to ride public transit.

Interview with Alaina Lemon

Joshua Walker: You mention in your article that you did not plan on studying discourses and practices surrounding money when you first began fieldwork in Russia. Yet, like a number of anthropologists (myself included), you seem to have been drawn to money as a fundamentally significant, and incredibly complex, social institution. Much of the anthropological literature on money tends to alternate between the significance of analyzing money qua money (that is, as an important object of study in its own right), and as an index of larger processes of value creation and signification. How do you understand this question in your own work? What kind of influence has this earlier focus on money had on your subsequent research? What drew you to studying money in the first place?

Alaina Lemon: My 1995 dissertation had been subtitled Sincere Ironies; it explored the ways that, when Roma interacted with other Soviets, they found themselves called to perform Gypsiness. Expected to be natural masters of the stage, to be simultaneously hot-blooded and “always ironic,” Roma often faced an intractable impasse: while inhabiting exotic Gypsiness could afford a sense of magical prestige or a counter-hegemonic vantage, it also limited material choices and aspirations. Working though this led me to think about “counterfeit” more broadly.

Russian acquaintances told me stories about Gypsies that always seemed to involve sleights of hand and disappearing bills. I witnessed people deploy visceral qualia of objects that detach from bodies in order to define what lies “under the skin”—bloodlines, instincts, essences, “blackness.” Objects – or rather, modes of touching objects under certain framing conditions – performed “blackness” even more than did other ostensible markers of “race,” such as phenotype. To demonstrate this offered another set of grounds to argue that people such as Roma came to be racialized in a state that did not officially recognize “race.”

As you say, anthropologists often have alternated between analyzing money as money, and as always pointing to other relations and processes. I see all my work to tack across similar points of alternation. When I look at, say, a transcript of a conversation, the more I look, the more that possibilities for other intersections assert themselves. When trying to “follow the money,” I have so far failed to observe moments when people focus on pieces of cash in ways that do not also point to social relations at hand, and also outward and inward, backward and forward.

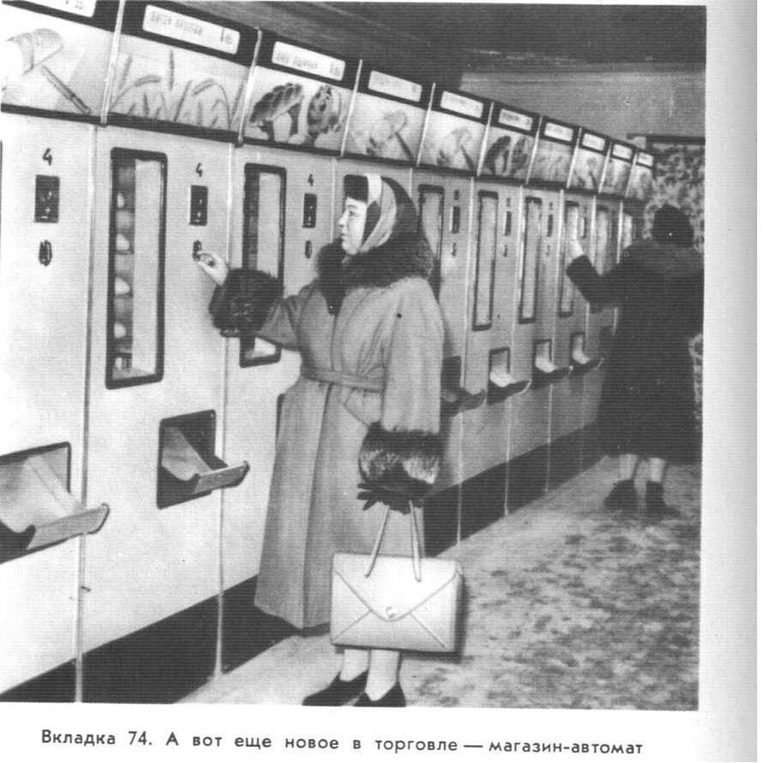

Many of us who began fieldwork just before and after the Soviet State fell wrote something about money or exchange. My favorites are in the bibliography. When I first lived in Leningrad in 1988, I was naïve enough to be surprised at the prevalence of physical pieces of money: Communism aspired to create a world that would not need money. But five-ruble coins went into slots everywhere: at the metro turnstiles, at machines that dispensed a glass of fizzy water. And people were interested in dollars. There was money to be made by undercutting the official exchange rate, to be sure, and yet people were curious about wages and prices elsewhere not because they planned some kind of arbitrage, it seemed, but perhaps because they wanted to imagine how others live.

At that time, one could hold a lot of rubles and not be able to spend them: many essentials were cheap, but others were hard to find. Until January 1991, official prices were centrally determined (even stamped on commodities themselves), but speculators could empty stores, workers could divert goods from assembly lines, factories bartered among themselves. This had been going on for decades. Much has been written about the Soviet second economy: people “acquired” bread, beer, theater tickets, apartments through privilege, barter, networks, and so on, “through someone.” But few had to worry about saving cash to pay the water bill (you thought about whom to visit when water shut off for other reasons).

I began two years of fieldwork three weeks before the August putsch of 1991. I saw the tanks roll through the center of Moscow, but I think the currency reforms from 1990 to 1993 were more traumatic for people than the regime change. After 1991, prices were released and the stores filled up, but inflation accelerated, creating a reality in which one had to recalculate prices for basic items every day. “You have to spin,” people would say. Industry could not keep up with hyperinflation to pay living wages, even as the state printed more and more rubles. Rubles were everywhere, buckets full, but never enough. More than before, the best way for ordinary people to “spin” was to buy U.S. dollars before rubles devalued, hide them in a sock, and trade back small amounts for rubles in order to buy groceries.

Dollarization has not been unique to post-Soviet Russia. Perhaps it emerges in diverse places through overlapping geo-financial conditions. All the same, dollars and rubles did specific “work” in 1990s Russia. Histories of international competition intersected Soviet events, social institutions, infrastructures and relations such that interactions involving dollars were shot through with Cold War-era anxieties.

Another thing that drew me to write about money was that, even in the midst of all this anxiety, I encountered people who worked hard not to count money, or to seem not to. Not in the markets or the shops, but where people aspired to friendship: companions smacking hands away from the cashier at an outdoor café: “Put away your paper!” In 1992, I mortally offended one acquaintance who, when I hesitated to mentally calculate, accused me of “Western coldness”; we had shared a meal, I had slept under her roof, how could I pause now to doubt, to count? In 2012, I do know Moscow friends who pull out a calculator on girls’ night out, but they have been neighbors now for decades. The other dynamic has not dissipated.

So money can absolutely serve “as an index of larger processes of value creation,” as you put it so well. I agree, but lately I am keen to unfasten “value” from metaphors of exchange, and also curious about how to theorize modes of sociability and action that cannot reduce our life with objects to strategy or calculation. Recent papers on sentiments for “broken” objects, on ways people deployed qualia to make Cold War “gaps,” and on encounters with “Metrodogs” try to do that.

JW: Your article raises the question of the relationship between value and materiality in money. Yet much of the recent literature on money in anthropology has become increasingly preoccupied with its immateriality and, some argue, increasing abstraction (global financial movements, electronic banking, etc.). How do you understand this question of the relationship between materiality and value in money today, both in light of theoretical developments in anthropology and changes you have observed in Russia since your first fieldwork there?

AL: Anthropologists might lose interest in money if it ever achieves full abstraction. Any form (metals, paper, digital numbers, names, brands) to which people assign capacities for storage, expansion, deferral, promise, liquidity, etc. can seem to become the medium for achieving dizzying levels of abstraction. But no amount of access to even the most convertible currency will buy most of the Romani families I know an apartment near the Kremlin. It is not lack of money that has kept African American families out of Oak Park.

The work of spinning money into “abstraction” involves leveraging contrasts between material and immaterial—and in turn leveraging those contrasts across social barriers. Who can only work for cash, whether for tips or illicitly? Who else can credibly flash minimal forms for credit? Who can’t spend even cash money without raising suspicion? Who can call someone who knows someone at a bank “offshore”? Abstraction works for someone.

In Russia, what has most changed are the forms of available contrast. Regarding contrast on monetary to non-monetary forms of exchange: one no longer needs networks to buy bread or toothpaste. Regarding contrasts among currencies: since 2002, the dollar competes with the Euro; at exchange points and in the news, people follow both rates. ATMs at every metro station offer the choice to receive dollars, Euros, or rubles. Moreover, the rate of the ruble to other currencies has remained much steadier over the last decade (in 2012, popular tabloids were advising people to hold onto their rubles). Regarding contrasts of currency to forms of credit: some people have had credit cards for a good while now, and advertisers promote credit for cars or apartments.

Still, people do keep reserves in foreign currency, both physically and in bank accounts. There are, in fact, more hard currency cash exchange points than in the 1990s, several on many city blocks. The posters near exchange cashiers’ windows demonstrating how to distinguish a counterfeit bill are even more elaborately detailed. U.S. dollars continue to pervade urban streetscapes and visual media. Have a look, for instance, at this video news report (circa 2010) on counterfeit dollars. At about 1:03, you should see a close-up of hands touching currencies, edited under the voice of an official who lays blame for the bills on the “North Caucasus”:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YsSlK9mvgAU

Financial or market-based definitions of value remain only part of the story: this encounter with money explicitly indexes the geopolitics of war.

During the 1990s, the exchange rate allowed Americans to live extravagantly on very little. This is no longer the case, and I like it better this way. It is clearer that U.S. is losing ground in its attempts to assert cultural hegemony in Russia, although people still worry about “mental colonization,” and about the military presence ever closer to the borders in Central Asia and in Europe.

JW: One of the interesting observations about money drawn out by your article concerns the reading of signs, and the perception of a murky relationship between what people conceive as its surface appearance and inner substance. How do you understand money as a sign, and in what ways – if at all – do its semiotic properties elucidate questions about the nature of signification more generally?

AL: One example. To attend to ways people concretely reject certain forms of cash or counterfeit cash (“They won’t take your money here!”), might provide purchase for investigating how people work through conditions for semiotic and performative infelicity more broadly. To focus on failures—and on what failures yet produce socially—would, for one, undermine Saussurean exchange metaphors that still underwrite misunderstandings at large about “language.” Helpful as Saussure can be for mapping active binaries (and people do love their binaries), they are only part of any story.

Cash tokens and specific bank transfers are always uttered by some entity or entities for some entities, like a Peircean sign. This allows for complications, mutations across chains of action when interpretants don’t match up. We can make schema from phonemes and we can “float” currencies. But just because we cannot see each and every movement that monetary or linguistic “utterances” make along chains of action does not mean that any resulting phenomenological sense of abstraction represents the world – even while perceptions of abstraction become interpretants/signs that can have very real effects.

To take the metaphor of specific cash “utterances” to the extreme, to borrow from Voloshinov: it might be interesting to think about credit, and ultimately state-backed cash, as “reported money” (we could even better discuss claimed distance: “It’s not mine, it’s my parents’ money”…).

How people become enmeshed in meta-communicative discourses that separate surface appearance from inner substance is another level of the problem. My first book addressed the interplay of “surface” and “depth,” without dismissing one or the other as more real or superficial. For instance, actions and objects that non-Roma dismissed as signs of Gypsy inauthenticity, kitsch, cultural loss, or venality were often the very objects that Roma framed as vital to collective life, signs of effort keeping “us together in one place”: a pack of Kosmos cigarettes at a wedding, a brick of rubles a foot square, wrapped in plastic, on the kitchen table: “This here is money my son gave me!”

That particular knot, the mask/essence paradigm, has become all too powerful in scholarship on the former USSR, projected into “explanations” of Russian and Soviet Culture, even despite the efforts of some of our colleagues. Teasing out how this has come to be and continues on, and most of all, what that does for whom, is central to the book I am finishing.