A Brief Review of "Sin Cesar"

From the Series: Haptic Encounters of the Extrajudicial Kind: A Review Forum on the Photo-Book "Sin Cesar"

From the Series: Haptic Encounters of the Extrajudicial Kind: A Review Forum on the Photo-Book "Sin Cesar"

23 December 2022

Within a week of his inauguration in August 2022, the president of Colombia, an ex-M19 guerrillero, fired the top echelon of the armed forces and police—some fifty-two generals. Many thought it a rash move. But then the police and army had long lost even the shreds of legitimacy with the revelation a decade earlier of the “false positives” scheme whereby soldiers were rewarded for secretly murdering civilians and dressing them to look like guerrilla fighters—six thousand in all. Some soldiers got cash for each “guerrillero,” some vacations, others promotion. This was merely one element in the steady disappearances and massacres in the rural areas of Colombia since the 1980s, largely attributable to right wing paramilitaries working closely with the army, land and coca being at the heart of it all, alongside tacit U.S. government support.

The curious and highly original hand-made artisanal book, Sin Cesar, designed and hand stitched together by the Editorial Entrelazando in Bogota two years ago, purports to tell us about this in and around the hamlet of El Copey in the northern Department of Cesar. The book’s title, Sin Cesar, is a play on words meaning “Without End.” The impact of terror is rendered not through narrative or the form of a graphic novel (thank the Lord), but through a sense of immersion in the thingness of things, same as an ethnographer would experience a fearsome reality as confusing and visceral without losing sight of its principal causes.

The book does not so much represent reality as it is reality. There is a medley of color photographs inserting you into forest and scrub, nightfall on town streets, maps of cemeteries, forensic teams at work, and an elderly man photographed from behind while walking under giant trees, shoulders hunched, his curt speech like hieroglyphs quoted on the page following. There is no direct depiction of violence.

It is in other words an ethnographic scrap-book with the overall effect of what I call “deep metonymy.” The reader—or should I say participant—has to work through assorted materials, shapes, colors, and textures; different types of lay-outs, actual photographs, pages which open up like fans, others like secret compartments inserted as miniatures, newspaper clippings, and memoranda of the U.S. Department of State. The book is made of different types of hand-made, thick-textured, paper whose fibers glow, placed alongside semi-transparent pages and coal black inlays—all hand sewn.

Although there are four pages in small print at the end of the book citing sources and references, strange to say the pages of the book, are not numbered, which makes it hard to match things up.

You “read” sub-consciously as befits both the rendering and interpretation of the violence of violence and its confrontation. Here, opacity is an essential part of the public secret with which paramilitary violence, like Deleuze and Guattari’s “war machine,” flourishes.

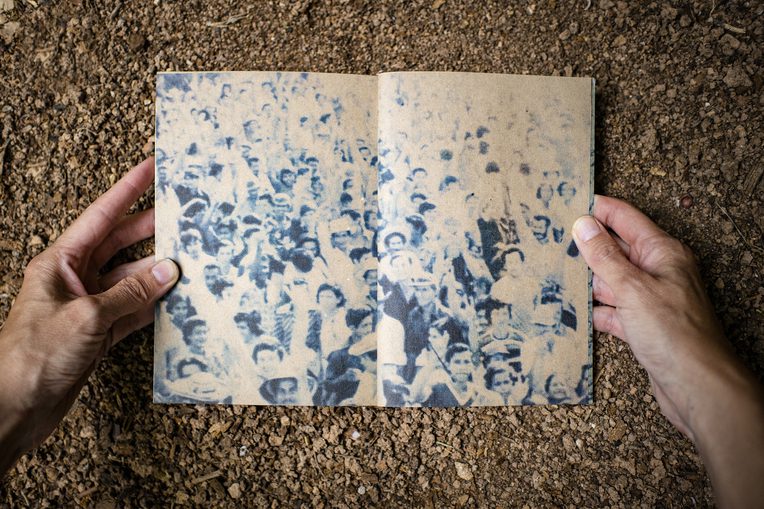

The end pages, front and back, are magnified images of human tissue, traceries like spider webs, pink, blue, and black, as seen through a forensic microscope attempting to identify the assassinated. Turn the page and you plunge into a blue sea of human faces in an immense crowd. Perhaps your face and mine are present too because, so it seems, it is as collective witnessing, at the level of sub-conscious awareness, and only so, that justice will one day announce itself.

Fin.