Laura and I scramble to find a quiet place to talk in Bogotá's busy colonial downtown, La Candelaria. Sunlight barely bursts out through the thick, rain-laden, grey clouds of a typical afternoon in Colombia's capital. Oficinistas, or office workers, are flooding every café and restaurant—the one-to-two-hour lunch break is a sacred communal rite in this country, I swear. We eventually find comfort in a revamped former Israeli hostel, now a stylized café offering hookahs and clad with stereotypical fabrics from the Middle East. Laura, a Spanish national, has been living and working in Colombia for well over a decade. An anthropologist herself, she was part of a research group led by Francisco Ferrándiz studying the politics of memory in the exhumation processes of mass graves from the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), helping her build a comparative framework regarding reparation, truth, reconciliation, and historical reconstructions. Upon first learning about Colombia's internal armed conflict, which is, ostensibly, larger in scale and more complex—both in the multiplicity of historical timelines and range of actors—, she was intrigued and wanted to know more about our transitional justice system. She arrived in Bogotá, went through a whole lot of footwork visiting affected communities, and chiseled out what would become her proposed doctoral research. What brought us together, that day, revolved around a topic we are both passionate about: Colombian cultural production inquiring into the country's armed conflict, specifically through photography. The growth of quality photographic work since the early 2010s, from a technical perspective, especially given its ingenious aesthetics, is astounding. We came across multiple names; a lot of them have a background or are familiar with anthropology. However, there is that one issue keeps steering our discussion towards a pressing matter: photography makes for truly precarious wages in Colombia, to the point that up-and-coming talents desperately take up any work, disregarding the politics and ethics behind a project or a “client's” track record. It is in this milieu that the term “client” becomes even more unsettling. Besides Colombia's large state-owned humanitarian bureaucracies and their poorly compensated months-long contractual work, “clients” are often international cooperation agencies which come each with agendas that are supposedly beholden to the interests of their home countries' constituents. Add that to the looming crises of tuition-driven private universities in the country (and the whole world) and you have a potential nightmarish scenario for critical multimodal research.

It is perhaps no secret, but foreign aid is given on condition of “x” or “y” and the work that you do for them, be it as a photographer, a researcher, or an artist, and aid is gauged according to the political and developmental prerogatives of the funding. Of course, this is true of any NGO or non-profit work within the very same countries of the Global North. Yet, most international cooperation agencies operating within the country are also partners in Colombia's peace building processes and some of their host countries act as guarantors of an alleged transparent implementation of transitional justice mechanisms (the main three being the Truth Commission [CEV], the Special Jurisdiction for Peace [JEP], the Search Unit for the Disappeared [UBPD]). This endeavor in itself has real consequences, particularly affecting the lives of people that continue to be assailed by entrenched violence and rampant impunity. So, if salaries are conditional on prerogatives you yourself as a photographer are not acquainted with, is multimodal research/work just a publicity stunt promoting the good will of the whomever people of wherever? Public diplomacy between Colombia and its partners in developmental humanitarianism, for both Laura and me, is the one to reap the real benefit from sponsoring avant-garde documentary photography (surely, a rather sophisticated pat in the back). After all, former President Juan Manuel Santos, the intellectual author of Colombia's 2016 peace agreement, clearly stated that the “economic model” of the country would remain untouched when negotiating the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of Marxist-inspired insurgencies. Unsurprisingly, most of the work of talented photographers we were discussing, albeit mesmerizingly beautiful and intriguing from a conceptual point of view, did not as much glean the surface of the most troubling fact underlying this messy state of affairs: this “economic model,” with all its vast land grabbing and forceful displacement schemes (to produce what? African palm by the thousand of acres? Trees that fail to nurture but cover up for the disappearance of bodies?), the very same model that international cooperation helps re-build by virtue of humanitarian ideals, is at one and at the same time responsible for the crimes against humanity Laura's and Ariel's work seek out to denounce head on.

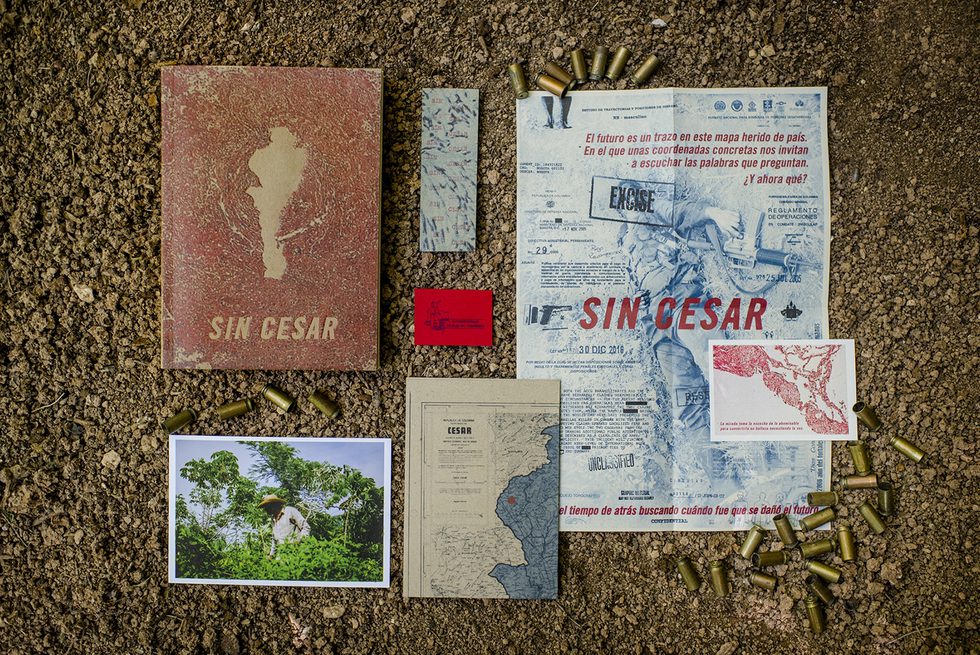

Our shared indignation is fueled by a further question: how else are you supposed to produce meaningful work, work that unsettles, work that confronts and interrogates (yes, you, the reader), by way of poignant images and haptic attunements, if not by crafting independent photo-books whose proceeds can (hopefully, yet unlikely) cover research and production expenditures? Laura tilts her head, and retorts: “There's hardly any alternative to being compliant with liberal capitalism in the midst of widespread violence. Ariel and I do not want to work for institutions, organizations, international cooperation or development agencies that are not aligned with our politics. This book is our own way to contribute a grain of sand (contribuir un grano de arena) and ours alone.” I believe her. From all the working photographers and independent researchers I know in Colombia (and I am proud to say I personally know quite a lot), they remain among the few that shun away from carrying out the biding of foreign aid without due critique. Theirs is the work of courage, commitment to unveiling injustices, and exquisitely well thought-out design.

— Alejandro Jaramillo, ed.

Posts in This Series

Sin Cesar or Ethnography Turned Tremor

Translated by Blossom Ah Ket. In one of his most harrowing books, the poet Antonio Gamoneda (2003, 120) (perhaps bringing to the present a childhood of fear and... More

A Brief Review of "Sin Cesar"

23 December 2022 Within a week of his inauguration in August 2022, the president of Colombia, an ex-M19 guerrillero, fired the top echelon of the armed forces ... More

El libro-objeto como testigo de la desaparición: narración, materialidad e imagen sobre las violencias paraestatales en Colombia

English translation below. Una herida abierta en el territorio; un mar de palma y carbón explotado hasta su agotamiento; una fosa sin nombre; silencios sin escu... More

Sin Cesar: The Healing Potency of a Book

Even as one who dreams that he is harmed and, dreaming, wishes he were dreaming, thus desiring that which is, as if it were not, so I became within my speechle... More

SIN CESAR: Extractos de qué es, de cómo se hizo o más bien por qué lo hicimos

English Translation belowLo más perturbador del espanto es que no constituye una excepción. Quizás por eso se escribe tanto sobre violencia y no por impulso c... More