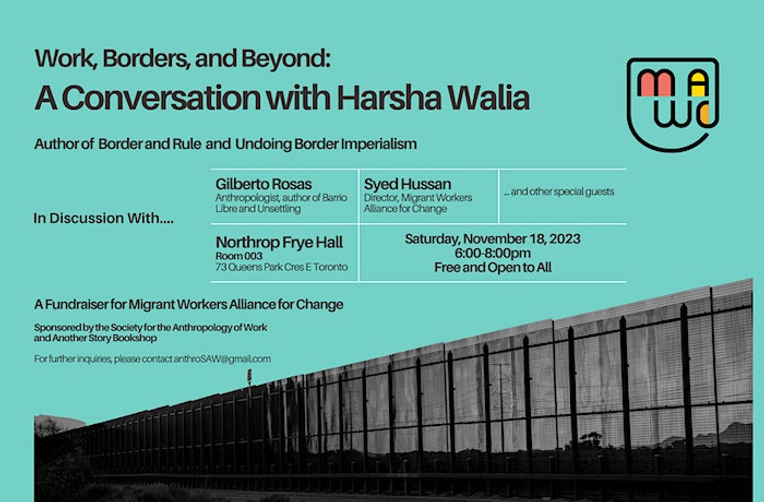

A discussion featuring Harsha Walia, alongside community organizers and migrant workers representing Migrant Workers Alliance for Change (MWAC), took place at the American Anthropological Association's 2023 Annual Meeting in Toronto. This episode is the first part of a two-part mini-series highlighting the impact and contributions of Harsha Walia’s scholarship.

Guest Bios

Harsha Walia, a South Asian activist and writer, residing in Vancouver on unceded Coast Salish Territories, has dedicated over a decade to various community-based grassroots movements, including migrant justice, feminism, anti-racism, Indigenous solidarity, anti-capitalism, Palestinian liberation, and anti-imperialism. She is the author of Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism (Haymarket Books, 2021) and Undoing Border Imperialism (AK Press, 2013).

Syed Hussan, Executive Director, Migrant Workers Alliance for Change.

Sarom Rho is a community organizer with Migrant Workers Alliance for Change.

Jess is a migrant worker and member of the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change.

Migrant Workers Alliance for Change (MWAC) is building a member-led organization of migrant farmworkers, care workers, students and more to win worker and immigration justice.

Credits

This episode was produced by Contributing Editors Alejandro Echeverria, Sharon Jacobs, and Deborah Philip, with review provided by Steffen Hornemann.

Intro song: All the Colors in the World by Podington Bear

Transition Music: Ambient R&B by YellowTree

Logo designed by Janita van Dyk.

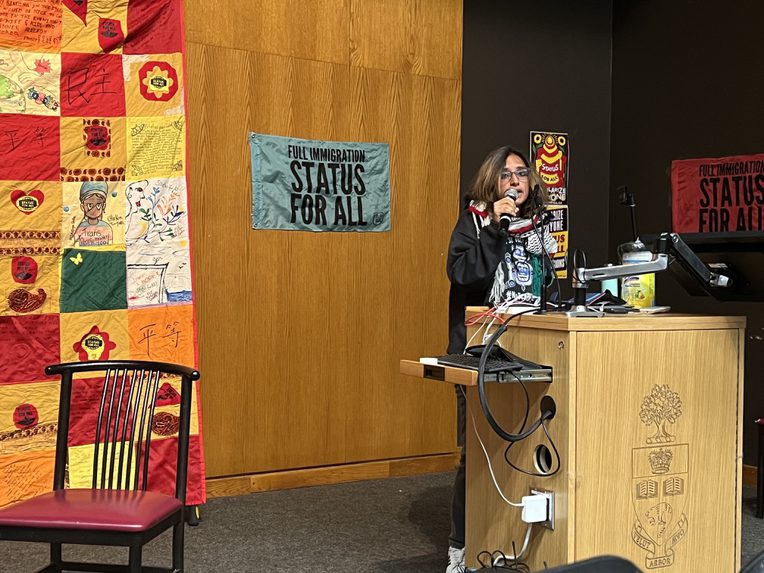

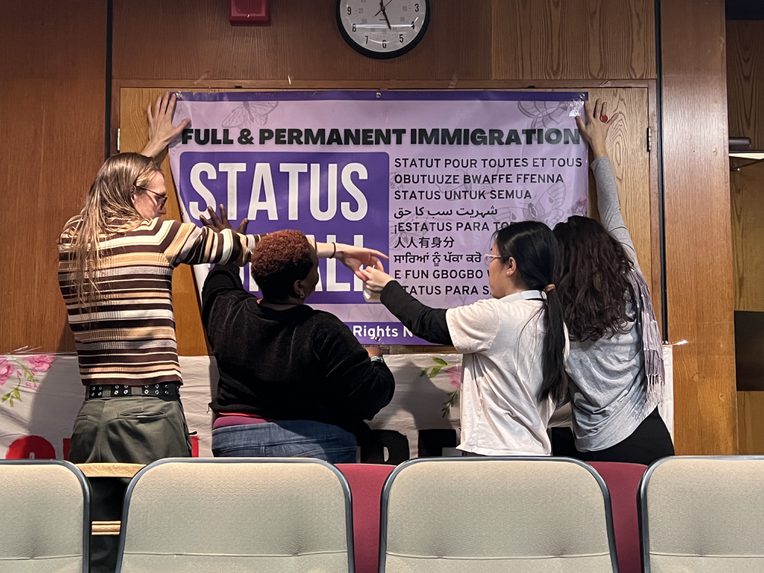

Event photographs courtesy of Jenny Shaw, who serves as the Mentorship Coordinator for the Society for the Anthropology of Work.

Transcript

Syed Hussan (SH) [0:00]: Let us begin with the absolute certainty from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free. Will be. It will happen without question or doubt. We believe in this future patiently, and yes, relentlessly.

Alejandro Echeverria (AE) [0:22]: You’re hearing the voice of Syed Hussan, executive director for the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change (or MWAC). Hussan’s call for the liberation of Palestine was part of an event at the American Anthropological Association, or AAA, annual meeting in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, in November 2023 celebrating scholar-activist Harsha Walia.

Sharon Jacobs (SJ) [0:44 ]: The event that we’re sharing with you in today’s episode was an MWAC fundraiser that featured a discussion between Harsha Walia, community organizers, and migrant workers representing MWAC.

Deborah Philip (DP) [0:55]: In this episode, we will be focusing on the testimonies that community organizers and migrant workers made at this event, particularly about the injustices and hardships they face in the workplace and their envisioning of a new just world—which includes Palestinian life and liberation. Throughout the episode, you’ll hear from members of the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, as well as Harsha Walia herself.

SJ [1:24]: This is the first part of a two-episode mini-series showcasing two roundtable discussions held at the 2023 AAA meeting. Each roundtable highlighted Harsha Walia’s impact in a different way. The second episode of the mini series will focus on academic scholarship. Now back to Hussan…

SH [1:47]: Palestine will be free. Because Palestine lives. Palestinians live. Despite the atrocities in each day they wake up. And as Refaat told us, they teach the rest of us life. Palestinians live touching keys to their homes, homes to which they will one day most certainly return. Free, in our lifetime, for our ancestors and for our children. The world we hope for everything we need is coming. We will not see another child crawling out from the rubble. We will live in a world without war, without rich or poor.

AE [2:37]: Hello and welcome to AnthroPod: The Podcast for the Society of Cultural Anthropology. I’m Alejandro Echeverria.

DP [2:44]: I’m Deborah Philip.

SJ [2:45]: And I’m Sharon Jacobs. The Migrant Workers’ Alliance for Change (or MWAC) is an Ontario-based advocacy group that has been supporting the self-organization of farmworkers, care workers, factory workers, student workers, and other migrant workers since 2009.

AE [3:04]: Today’s episode wouldn’t be possible without Jennifer Shaw, Alex Blanchett, and the individuals from Migrant Workers Alliance for Change.

[03:14 Podington Bear—All the Colors in the World plays]

Sarom Rho (SR) [3:38]: You'll see at the front that our members have carried things and items that we use to work, to live, to make the world that we live in. It's the gloves we wear to pick fruits. It's our muddy boots. It's the shovel that we use to dig into the earth. Our work uniforms as we move from health care facility to employers’ homes to health care facility, the bag that international students use to deliver food through cold and snow. These are the things, and these things have life. And we as migrants work with these things. Use them in our day to day to make this world possible.

DP [4:17]: This was the voice of community organizer and migrant worker Sarom Rho, who shared with us the ways migrant workers use certain items to build things, cultivate food, and make a living. But they are objects that are also part of a new world without borders. This narrative touches on Walia’s first point on the centrality of borders in countless aspects of our lives. And how the struggle for liberation is found on the border logic. Here she builds on what Migrant Workers for Change have discussed within their advocacy efforts.

Harsha Walia (HW) [4:56]—(First point—migrant struggles and border centrality):

The first point that I want to make is the centrality of the border logic today. Migrant struggles are central to so many of our struggles with resurgent white nationalist, anti-trans, and xenophobic fascism, the border is the central site of struggle. Far Right appeals target foreigners for “stealing our jobs, driving up our housing prices, draining our services, ruining our environment, infecting our neighborhoods,” all in quotes, of course, and tainting our so-called values. This is not only racist, but it also deflects responsibility from the capitalist colonial oppressive systems producing mass inequality, impoverishment, and misery by conveniently scapegoating migrants. We know, for example, that the housing crisis we're facing is not due to migrants, but is a symptom of the ongoing dispossession rooted in colonialism and the commodification of housing under capitalism. I want to propose further, it is not just that the border is a lynchpin in fascist ideologies today, but that fascism is itself constituted through the border. Fascist tendencies and the violence of seemingly fringe far right groups require the quotidian state violence of the border. The exclusionary projection of who belongs, who doesn't, who is more worthy, who is not, who can live where, and under what conditions, is possible because of an enduring global racial apartheid that borders uphold. Many Canadian immigration laws have long been written through explicit racial exclusion, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, vagrancy laws that deported the poor or those deemed criminal, attacks on labor unionism were carried out through the expulsion of communists and anarchists. Many laws excluded single women migrants deemed to be sex workers, and medical examination was and is a continued basis for excluding disabled migrants. The mass production and social organization of difference is at the heart of border craft, making both the so-called good versus bad migrant as well as maintaining the colonial racial, gendered, and sexualized ableist and classist orderings amongst all of us that fascism relies on. [7:07] In Europe, in the U.S. and in Canada, recent surveys have shown that anti-immigrant sentiments bound up in Islamophobia is a primary reason voters support far right electoral parties. This means that our responses to far-right escalating fascism cannot be through liberal moralizing about how good immigrants are or how much immigrants contribute or integrate. We must strike at the heart of fascism itself, which is to say to be anti-fascist is to abolish the border. Our enemy today arrives in a limousine and not on a boat, and our fiercely internationalist struggles are not against so-called foreigners, but against any and all oppressors.

[07:55 YellowTree—Ambient R&B plays]

SH [8:10]: Many years ago, I was at a protest here in Toronto, outside an arms manufacturer that was exploiting arms to yet another genocidal impulse by the Israeli government. After the march I was at a bus stop, and I met a woman who just had come outside of that function. And she told me that she was Palestinian, and that she had shrapnel embedded in her head. And that shrapnel, that bomb, had been made by SNC Lavella. And she was a cleaner at SNC Lavella. She came to Canada, applied for refugee status, and was denied. She stayed here and became undocumented. So she worked as a cleaner in the same factory that made the bomb that killed her people. And she had shrapnel embedded in her head from. They try to kill us, displace us, take our food, to spoil our water, and then they force us to come here to clean to care for them to feed them. And every turn, they tried to squeeze the life out from us, but we live.

SJ [9:28]: In the segment you just heard, Syed Hussan of the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change discusses the unimaginable ways displaced people are exploited and made to suffer by settler colonial governments and corporations. The grueling account Syed shares with us connects with another point in Harsha Walia’s speech, about displacement and limited mobility.

HW [9:52]—(Second point—displacement and constricted mobility of global migrant crisis):

The second point that I want to make is that immobility and displacement—not free movement—are the defining realities of our era. The global migration crisis is better understood as a crisis of mass displacement and the systematic constriction of human mobility. The total number of migrants worldwide today has reached almost five percent of the world's population. An emphasis on displacement, rather than migration, forces us to interrogate the real drivers of this displacement: conquest, capitalism, and climate change. Palestinians, for example today are considered in U.N. policy-speak as the world's “most protracted refugee population.” The Palestinian refugee crisis, as we know, is inextricable from the ongoing Zionist occupation of Palestine since 1948. And the ongoing freedom struggle for Palestine from the river to the sea.

This is why so many movements say, we are here because you are there. We cannot talk about immigration as a domesticated policy issue. This is not about quotas, or legality, or humanitarianism, or space and resources. This is about global capitalism, white supremacy, class, gender, caste, imperialism, and so on. Today, displacements are escalating with climate disasters. Around the world, an estimated one person every two seconds is being displaced due to a climate catastrophe. Further, when we say migration, and migration crisis, we tend to assume that millions of displaced people are able to move. Despite the constant border panics and language of swarms and floods and caravans, the reality is that over ninety percent of forcibly displaced people remain internally displaced or in refugee camps. People are not able to move because border controls are deadly and people are being contained at border sites in refugee camps, through interdiction, pushbacks, restrictive visa requirements, smart AI borders and more. [11:53] But language such as “border crisis” or “migrant crisis” is an excuse to further harden borders and depict and villainize migrants and refugees, especially those who are Black, Indigenous, and/or Muslim.

We see the racial colonial pillars of bordering regimes most starkly in the global response to Ukrainian refugees, including the racial differentiation of Black, racialized, Muslim, and Roma people fleeing Ukraine. Increasingly, borders are being outsourced so that border violence is happening far beyond the territorial border itself. Put another way, the border is elastic, and the magical line can exist anywhere. It can extend far within and far beyond the border, and it can take many forms. Canada, for example, does not need a big border wall because we have the Safe Third Country Agreement, first implemented by the liberals in 2004, and recently expanded by Justin Trudeau. This agreement forbids people who arrive in Canada at official land ports of entry from making a refugee claim. And when it was first implemented, asylum claims in Canada have dropped by over thirty percent. As legal routes become closed, people are continuously forced to rely on more and more irregular and unsafe and dangerous routes, where death is inevitable, as we saw the horrific deaths of eight migrants in the river on Akwesasne territory earlier this year. Similarly, the U.S. is funding immigration enforcement deep in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Colombia to prevent people from even reaching the U.S.-Mexico border. Shortly after the U.S. launched the Mexico-Guatemala-Belize border region program, Department of Homeland Security officials declared that “the Guatemalan border with Chiapas is now our southern border.” Mexico now has one of the world's largest immigration detention systems and deports more Central Americans than the U.S. Let that sink in. This is happening around the world, including the horrors we see unfolding in Europe and the Mediterranean. [13:55] And this is because countries like Nigeria, Libya, Mali, Mexico, Niger, Papua New Guinea, Rwanda, Turkey, and Sudan, are becoming the new frontiers of border militarization.

The outsourcing of border violence in this way is not only globalizing the violence of borders, it is also becoming an additional means of preserving global imperial relations, as countries in the Global South are forced to accept migration checkpoints, migration deterrence campaigns, and outsource immigration detention centers in exchange for trade and aid. At the same time, migrants are routinely victim-blamed for their own deaths. Why did they cross the desert in the heat? Why did they put their children on a flimsy dinghy? Much like victim-blaming discourses in rape culture, these kinds of victim-blaming responses are intended to shift responsibility away from bordering regimes that constrict migrant immobility and vulnerability. And to add insult to injury, the new mantra of “smuggling, trafficking, and organizing crime” is becoming the latest means to launder further violence. These crackdowns and further criminalization, especially on migrant sex workers as the work of Butterfly here locally, highlights are often justified as rescue operations and grossly analogized to modern day “anti-slavery efforts.” This is a crisis not of the border, but due to the border. People are not illegal. People are made illegal by the border.

I want to share a quick story that ties some of this in. As some of you probably know Canada has an intensive resource extractive economy. One that is heavily dependent on the extraction of resources locally and globally. Seventy-five percent of the world's mining companies are headquartered in Canada. There is no continent on this Earth where a Canadian mining company or subsidiary does not operate. And many of these companies are notorious for human rights violations, environmental degradation, for paramilitary deaths of land defenders, poisoning the water, for displacing entire communities.

[15:55 YellowTree—Ambient R&B plays]

Jess (J) [16:09]: So I applied for the Canada agency. Let them know my situation, that I was abused on the farm and want to have a hope and work permit. As I said, my goal is to provide for my family. I was unable to do so. And I still intend to do so because that's the reason why I'm here. Let them know all of that, they still refuse that open work permit. So as I said, it's a slave trade. And not until these people wake up and realize we are human. We need to live happily just like any other person living in this world. Because when we are in our country, we are happy. So why would you say “welcome?” You hear about the barber liners or member stated that's where you and us, that slave mark, our slave tattooed on our papers right there. You've become our slave master. This is a first-world country, and you're treating us like a slave. As I said, I watched the movie but never knew I would live that story till I come to Canada. And I'm still living like that because, I'm, I'm living like rats. I'm hiding from the cops, from the federal government. I cannot work, I'm jobless. Because I don't have a permit. And as they say they want to keep us tied. Why do we need to have a work permit to provide for ourselves? We already here. Makes things possible for us to provide because I said, you can't work to provide. Are you hiding to do so, you will not accomplish anything?

AE [17:40]: This was the voice of Jess, a migrant worker from Jamaica who moved to Canada in the hopes of making an honest living. Jess shared some of her experiences of living life in Canada which she described as living as a slave in the twenty-first century. Jess’ story connects to Walia’s third point on freedom, labor, and mobility.

HW [18:01]—(Third point—mobility made by freedom and unfreedom):

Perhaps, most ironically and offensively, the migration crisis is declared a so-called new crisis, with Western countries positioned as its primary victims, even though for four centuries, nearly eighty million Europeans became settler-colonists across the Americas and Oceania, while four million indentured laborers from Asia were scattered across the globe, and the transatlantic slave trade, kidnapped and enslaved fifteen million Africans. Colonialism, genocide, slavery, indentureship, and extraction are completely erased in current invocations of a so-called migration crisis, even though they are the very conditions of possibility for displacement today. Police, prisons, borders all operate with a shared logic of immobilization. Notably, the word “mob”—a criminalizing vocabulary used to link large groups of poor racialized people to social disorder, including in inner cities and at the border—derives from the word “mobility.” In fact, what we are witnessing is a relentless crisis of immobility across and within borders. While migration is typically analyzed through borders and bordering, what I think we can think through is how to think about displacement and immobility more expansively, which allows us to see how the border, the prison, the sweatshop floor, the refugee camp, the reservation, the gentrified gated community, are all immobilizing regimes that operate through dispossession, capture, closure, and criminalization. These are all bordering regimes, or we could say “ordering” regimes that manufacture and discipline and immobilize populations under capitalism and colonialism. As Angela Davis and Gina Dent write, “We continue to find that the prison is itself a border.” The prison is a border and the border is a prison, and borders and prisons must be abolished.

[20:01] The last point I want to make is that this immobility is produced and reproduces social and labor on freedom. Borders are not intended to exclude or deport all people but to create conditions of deportability. Workers’ labor power is captured and immobilized by the border, and this pliable labor is exploited by bosses. After its formal inception in 1924, U.S. Border Patrol was actually overseen by the Department of Labor. Capitalism requires labor to be constantly segmented, and the border acts as a spatial fix for capitalism by bifurcating the labor force. According to one study, fifty-two percent of companies in the United States threatened to call immigration authorities on workers during union drives. This shows us, that the border works in the interest of capital and not against it. This is why some of those on the left who believe that somehow more border enforcement is better for workers are completely racist and misdirected. Migrant workers do not suppress wages. Bosses and borders do. While workers are declared illegal, the surplus value they create is never deemed illegal. And this is the reality of why we have to support organizations like MWAC and MRN because Canada's internationally lauded model of permanent temporary work is a perfected system of managed migration that ensures the steady supply of cheapened, disciplined labor indentured to an employer, while further entrenching racialized citizenship. The precarity and disposability of migrant workers is specifically because of their migrant status, produced by the border. This is not because of just a few simple bad employers. This is the relationship between the border and bosses. This is why so many migrant worker organizations are calling for full immigration status, and are calling for struggles to understand that migrant workers struggles today are the heart of class struggles against capitalism. [22:01] This is why it is essential for anti-capitalist movements to echo the internationalist call for full immigration status for all workers, effectively making the border obsolete. Papers for all or no papers at all.

[22:15 Audience claps]

[22:21 YellowTree—Ambient R&B plays]

SH [22:35]: Our members found out that the Jamaican Minister of Labor was going to be coming to your farm, and so, so how we organize is we organize committees of migrants on farms and factories, in warehouses and also kind of a general membership. And so they found out at the farm that they were coming, we had members, and they got together and they wrote an open letter to the Minister of Labor. And they said, “We know when you come here, you won't be able to see these things.” And that letter they sent to media outlets across Jamaica and to the United States—I'm sorry, the United States and Canada. And then the minister came. And when the minister arrived, he basically told them, we found this, to just shut up and take it. And then the minister left. And this started this massive pushback in Jamaica. People were marching, former farmworkers, to the point that the Jamaican—they were calling for the Minister of Labor to resign.

DP [23:43]: We just heard Syed Hussan’s account retelling the experience of migrant workers and members interacting with the Minister of Labor from Jamaica, who came to Canada to visit a farm where migrant workers were organizing for better working conditions. During his visit, the Minister told the migrant workers and members to endure the labor exploitation and mistreatment at the farm. Syed’s narrative connects with Walia’s analysis of how migrants experience inequalities and divisions across borders.

HW [24:21]—(Concluding thoughts on how borders maintain divisions, and power inequalities):

To conclude, borders are not lines marking territory, they're shaped by and shaped social relations. Borders are race-making, property-protecting, and labor-suppressing regimes of immobility. Put another way, borders maintain asymmetric relations of wealth accrued from colonial impoverishment, of mobility for some and mass immobility and containment for most—essentially, a divided working class and system of global apartheid. We often naturalize the existence of borders, which removes them from their long historical and contemporary entanglement with empire. Edward Said wrote of the so-called post colonial period, “The newly triumphant politicians seem to require borders and passports first of all.” In Home Toni Morrison describes, “The contemporary world's work has become a policing, halting forming policy regarding and trying to administer the movement of people.” A world without borders is not the same as a world with open borders. In an open borders world the world stays configured the way it currently is, with massive inequality, mass displacement, and continued hierarchical differentiation, except borders are opened up. If people are still being forced from their lands, and some parts of the world are being plundered as sacrifice zones for others, that is not migrant justice. A No Borders politics is more expensive. It calls on us to fight for freedom and to fight against all forms of displacement and immobility. The battle against borders is necessarily inclusive of movements against gentrification, of liberation struggles against colonial occupation, of the fight to be free from policing and cages of bosses and banks, of the dream articulated by queer trans feminist and disability justice movements of being at home in our bodies, and to ensure a habitable Earth for all living creatures. It centers the right to stay, the right to move, and the right to return. [26:21] In the words of Eduardo Galliano, “The world was born yearning to be a home for everyone.” The world was born yearning to be a home for everyone. And while this world without borders certainly requires us to stretch our imaginations, No Borders is also a present-day practical politics. Over the past twenty years, we've had a number of movement campaigns such as “education on deportation,” “transportation, not deportation,” and “shelter sanctuary status,” to remind our comrades, nurses, teachers, social workers, transit workers, that their work should not involve becoming border guards. The Migrant Rights Network, for example, is fighting for immigration status for all migrants and refugees and labor protections and universal public services for all. These kinds of fights render the border obsolete and strengthen our fight against austerity for all people. No Borders, then, is a way of analyzing the world. It offers a futurist vision. It is an internationalist framework for relationality and solidarity. No Borders is a present-day form of politics. No Borders is abolitionist imagination as reality. Empires crumble. Capitalism is not inevitable. Gender is not biology. Whiteness is not immutable. And prisons are not inescapable. And borders are certainly not fucking natural law. And all the laws and all the cages that we are surrounded by will fall. We will have border abolition in our lifetime

[27:45 Audience claps]

[27:53 YellowTree—Ambient R&B plays]

SJ [28:09]: We hope you enjoyed today’s episode, which was produced by Alejandro Echeverria, Deborah Philip, and myself, Sharon Jacobs. To learn more about the organizers whose voices you’ve just heard, the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, as well as scholar Harsha Walia, please visit our website at culanth.org. That’s c-u-l-a-n-t-h-dot-org. You’ll also find there a transcript of this episode.

You can make a donation to support the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change at their website: migrantworkersalliance.org.

Special thanks to Jenny Shaw and Alex Blanchette from the Society for the Anthropology of Work for organizing the roundtable discussion and proposing this mini series. And thank you for listening to AnthroPod, the podcast of the Society of Cultural Anthropology.

See you next time.

[29:05 Podington Bear—All the Colors in the World plays]