Anti-Ghosting: Teaching Ethnographic Film with Ghosts and Numbers

From the Series: Ghosts and Numbers

From the Series: Ghosts and Numbers

Ethnography is always haunted by the hubris of reductionism, which is why sound ethnographic writing often involves a resistance to closure, a resolve to suggest meaning rather than spell it out.

—Michael Jackson, “After the Fact: The Question of Fidelity in Ethnographic Writing”

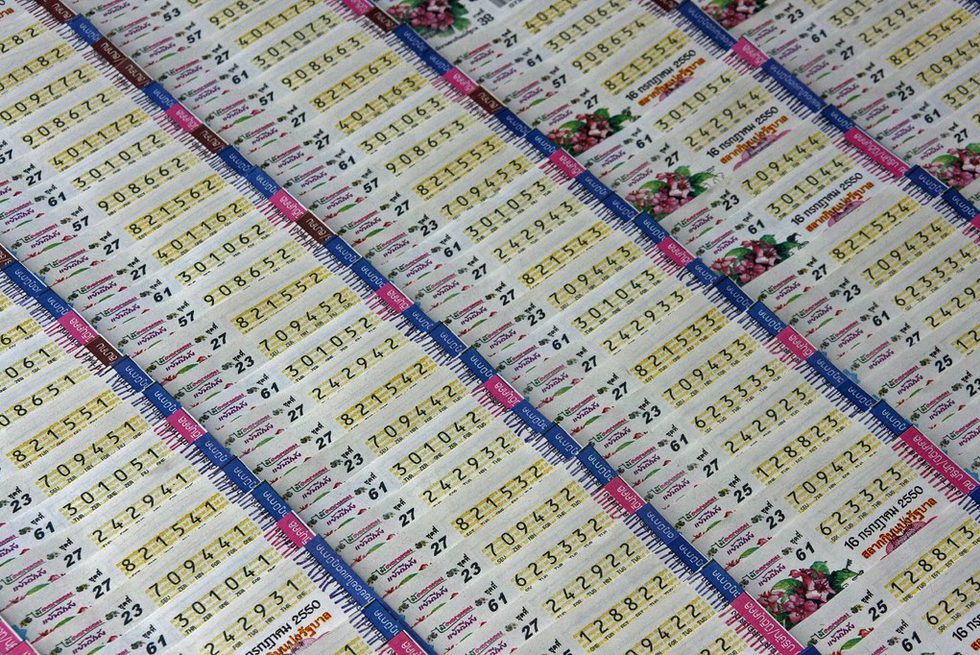

Moving through an anxious “spiral nightmare of numbers,” Ghosts and Numbers (Klima 2009) hauntingly conveys the tangle of spirituality and economy in Thailand. Following the devastating Asian financial crisis and the crash in the value of the Thai bhat, the film flows through jarring juxtaposition and fragmentation. Meaning and significance burst unexpectedly from small encounters, the arrangements between which are always slightly askew. We follow lottery ticket sellers increasingly pushed to take their transactions to marginal grey zones throughout urban Bangkok by the rise of more “modern” ticket machines (and a deepening distaste for “superstition”), an elderly woman chooses her lottery numbers from the license plates of the car crashes she’d foretold in dreams, workers harvest rice in a flooded paddy, a mischievous spirit by the name of “Little Prince” doles advice through a medium, a man’s home—bricolaged from the remains of three previous houses—becomes haunted.

As the inaugural film in the experimental Screening Room collaboration, Ghosts and Numbers is particularly well suited for contemplating how we teach ethnographic film. While Michael Jackson made his argument with regard to ethnographic writing, classroom discussion of ethnography also seems haunted by a hubris of reductionism demanding a committed resistance to closure. Under the exhausting “professionalization” of the university (Harney and Moten 2013), students are taught to think about thinking, and collaborative relationships (i.e., “networks”) in the sort of transactional terms and registers which are most often inimical to the kind of experimental and ethical transformations evoked through nonfiction film (Seale-Feldman 2019). For those of us laboring under adjunct/casual/flexible conditions in the “gigified” university, the specter of reductionism seems particularly haunting. How many of us lay awake the night before a lecture, staring at the ceiling, terrified that our experimental lesson plan won’t adequately and entertainingly convey the point of an ethnographic case study or a key concept?

As students and educators, we’ve been overwhelmingly ghosted by the unfulfilled promises of the commodified university under neoliberal capitalism. It’s not the students who are to blame for the palpable expectation many of us feel to simultaneously entertain (Fisher 2009), and compress time, to “just get to the point.” If the zoomer generations’ term ghosting can be theorized hauntologically, as a signifier for the collectively depressing sense of ennui that underwrites much of contemporary sociality (where static icons of riven relationships haunt), perhaps we can think of ethnographic pedagogy as a kind of anti-ghosting, a staging area for fomenting fugitivity in a spirit of anti-nostalgic necromancy, reanimating “the uncanny that one can sense in cooperation, the secret once called solidarity” (Harney and Moten 2013, 42).

Ghosts and Numbers embodies ethnographic film at its most surrealistically potent, a “carnival dance of image and word” (Taussig 2011, 7) through which juxtaposition subverts the idea of a singular “point” of meaning altogether. In its multi-sensorial positioning of the local alongside and through the global, ethnographic films like Ghosts and Numbers mediate experiences that we know to be simultaneously personal and political. Hopefully, students come to recognize their complicity and their subversive agency in relation to what are otherwise often disorienting political formations. We hope that through the Screening Room collaboration with the Visual and New Media Review, Teaching Tools contributing editors will feel moved to create relatively short (500–1000 words), “flexibly-structured” provocations, activities, discussion guides, and other strategies for animating these deeply moving ethnographic films in and beyond the classroom.

If the zoomer generations’ term ghosting can be theorized hauntologically, as a signifier for the collectively depressing sense of ennui that underwrites much of contemporary sociality (where static icons of riven sociality haunt), perhaps we can think of ethnographic pedagogy as a kind of anti-ghosting. . .

Teaching Tools is also looking forward to partnering with the Society for Cultural Anthropology's social media team to enliven and broaden discussion beyond individual Screening Room posts. As with the social media discussions around each faculty contribution, we hope Teaching Tools posts in Screening Room spark a vibrant and collaborative conversation centering ethnographic pedagogy in some sense, exploring experimental modes of teaching individual ethnographic films and nonfiction cinema more generally. Screening Room is an opportunity to explore the collaborative, ludic, imaginative, and creative sides of ethnographic film. We encourage contributing editors to collaboratively engage with the ways in which particular films help to elucidate specific concepts and content (e.g., the Asian financial crisis and global capitalisms), but also to consider how each film illuminates questions related to nonfiction film more generally (exploring, for example, the often ambivalent interplay of artistic creativity and documentation in ethnographic film).

As an example, the following discussion and activity guide, likely to be most useful for upper-division undergraduate and graduate courses in anthropology and ethnographic film, is designed to help students begin to visualize their relationship to a specific concept from the film (debt), explore the relationship between artistic creativity and documentation in ethnography, and solidify students’ grasp on ethnographic fieldwork methodologies. This discussion and activity guide is designed with flexibility in mind, allowing educators to choose those questions and activities that are most appropriate for their course.

Appel, Hannah. 2014. “Occupy Wall Street and the Economic Imagination.” Cultural Anthropology 29, no. 4: 602–25.

Causey, Andrew. 2017. Drawn to See: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method. North York, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Washington, D.C.: Zero Books.

Hamdy, Sherine, and Coleman Nye. 2017. Lissa: A Story About Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution. Illustrated by Sarula Bao and Caroline Brewer. Lettering by Marc Parenteau. North York, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Moten. 2013. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. Wivenhoe: Minor Compositions.

Jackson, Michael. 2017. “After the Fact: The Question of Fidelity in Ethnographic Writing.” In Crumpled Paper Boat: Experiments in Ethnographic Writing, edited by Anand Pandian and Stuart McLean, 48–67. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Klima, Alan, dir. 2009. Ghosts and Numbers. Watertown, Mass: Documentary Educational Resources.

Miner, Horace. 1956. “Body Ritual among the Nacirema.” American Anthropologist 58, no. 3: 503–7.

Rosaldo, Michelle Zimbalist, and Louise Lamphere, eds. 1974. Women, Culture, and Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Russell, Whitney. 2018. “Pedagogical Soundings: Feminist Anthropology.” Teaching Tools, Fieldsights, March 16. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/pedagogical-soundings-feminist-anthropology

Seale-Feldman, Aidan. 2019. “Cinematic Experiments and Ethical Transformations.” Visual and New Media Review, Fieldsights, January 10.

Strathern, Marilyn. 1988. The Gender of the Gift: Problems with Women and Problems with Society in Melanesia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Taussig, Michael. 2011. I Swear I Saw This : Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Weiner, Annette B. 1976. Women of Value, Men of Renown: New Perspectives in Trobriand Exchange. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Zaloom, Caitlin. 2018. “A Right to the Future: Student Debt and the Politics of Crisis.” Cultural Anthropology 33, no. 4: 558–69.