Ayurveda in the (Mis)Information Age

From the Series: Responding to an Unfolding Pandemic: Asian Medicines and Covid-19

From the Series: Responding to an Unfolding Pandemic: Asian Medicines and Covid-19

On March 28, 2020, in another instance of eventocratic governance (Kalyan 2020), Prime Minister Narendra Modi interacted with one hundred AYUSH practitioners through a teleconference

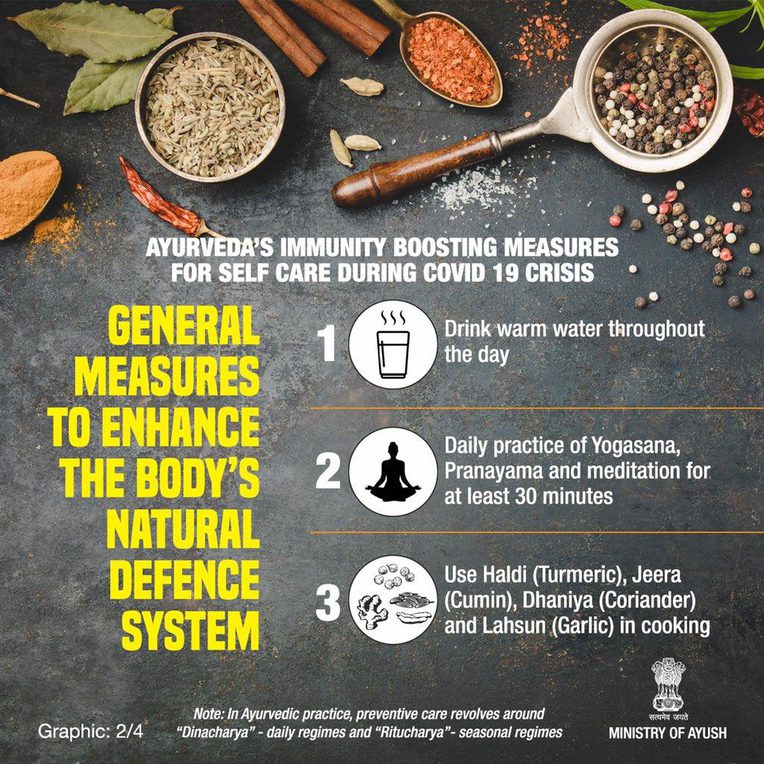

and urged them to counter misinformation and fact-check evidence.1 The remarks came after a flurry of curative claims and preventive guidelines began circulating on digital and print media (see Figure 1), including the Ministry of AYUSH’s rushed and much-criticized advisory

from late January. In the guise of controlling misinformation, the Government of India has prohibited (albeit selectively) advertisements and information about products related to AYUSH, and also placed several restrictions on reportage of Covid-19 related news. Ironically, some of the government’s own representatives have claimed cow urine as a cure while affiliated Hindu nationalist organizations have made international headlines by hosting cow urine drinking parties.

This article addresses the ubiquity of misinformation’s discursive presence in debates surrounding Ayurveda in the current pandemic.2 Scholars have argued that Ayurveda, like biomedicine, has been enrolled in biopolitical agendas of the state (Berger 2012). The biopolitics of Hindu nationalism sees the body as a site for biomoral regimentation (Subramaniam 2019). The current response has made evident that Ayurveda is also central to “misinformation governmentality,” a governance rationality that utilizes false claims in the organization of sociopolitical life but, more crucially, makes misinformation itself the discursive terrain for managing and arbitrating expertise and authority. Diverse idioms of “self-care” are employed, not only by the state but a range of other actors, to govern misinformation while also profiting from proliferating uncertainty. This, moreover, often relies on creating and managing cultures of fear (see also Mukharji 2012) that conflate “free-floating anxieties” from unrelated domains, anxieties about health and “terrorism,” for example.

To manage misinformation allegations, self-care is productively co-opted by the state. The ministry of AYUSH’s recent advisory recommended “immunity boosting measures for self-care.” It was signed by prominent vaidya, and carried a disclaimer emphasizing that the suggestions are not for “treatment” but only “prevention.” The guideline’s veracity was further enhanced when the Prime Minister’s own Twitter and Instagram handles shared these as visual infographics in both Hindi and English (Figure 2). Intriguingly, while the January advisory also carried recommendations from Unani and Homeopathy practitioners, the new one selectively draws from Ayurveda, evoking its special place as “national medicine.”3 By transforming well-trodden dietary and bodily practices into “codified expertise” (Nijhawan 2018), suggestions like drinking warm water, cooking with spices like jeera (cumin), haldi (turmeric), and lahsun (garlic), and consuming hot milk with turmeric, advance the home as a site where national resilience can be enacted. The epithet “preventive” further shifts the responsibility for pursuing these self-care projects away from the state, while extending its productive powers.

Meanwhile, the world of WhatsApp forwards and social media continues to feed “the mill of algorithmic capitalism” (Stalcup 2020). Google Trends’s search results for giloy, the herb claimed first as a cure and later as a preventive by Baba Ramdev, head of Patanjali Ayurveda, swelled in March just as his public presence on Covid-19-related issues increased.4 Ayurveda firms employ a range of marketing strategies (Bode 2007) that tap into diverse idioms of morality, cultural codes, and fears. Consider advertisements (Figure 3) for Joshanda, an herbal brew popularly consumed across Northern India and Pakistan. It is marketed as Ayurveda or Unani, depending on the place and the manufacturer. Circulating since February through WhatsApp groups in my hometown Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, these images combine the format of a product advertisement with the informational and visual aesthetic of a newspaper report. “Cup of Tea or Baljivan Joshanda: Your Choice, Your Health,” the headline announces, positing matters of health as matters of neoliberal self-care. The rest of the text links the contagion with predominant anxieties by stressing the “foreign” origins of the “Chinese virus” (see Lynteris, this series) and calling the pandemic worse than “terrorism.”

Regimes of misinformation governance further produce particular kinds of practitioner engagements. While practitioners may individually react to claims they perceive as misleading, there has been little attempt to collectively address misinformation outside of the state’s bureaucracy. Dr. Nitin Chaube, an Ayurveda practitioner from Singrauli, Madhya Pradesh, told me that individual practitioners’ engagements in the networked public sphere (Sinha 2019) are fueled by expectations to adopt “educative roles.”5 These educative roles, however, can be quickly capitalized. Distancing themselves from “tele-gurus” by asserting their professional credentials, celebrity-doctors assuage misinformation-anxieties by insisting that audiences learn the “know-how” of Ayurveda. OJ Ayurveda, a Hindi and Gujrati language YouTube channel with over 850,000 subscribers, is run by Dr. Arun Mishra, and in line with the DIY nature of YouTube, helps audiences discover their own prakriti as a first step toward self-healing. The ethics of self-care in Dr. Mishra’s discussions relies on rationalizations of all suggested claims. A video discussing Covid-19, for example, details different kinds of jwara or fevers that are listed in the Charaka-Samhita, one of the foundational Sanskrit medical texts. In another video, the suggestions in the AYUSH advisory are appreciated but their relevance is further qualified by referencing different dosha and body typologies. Practitioner-popularizers thus fashion Ayurveda as a self-care practice, insisting that the work of self-care begins with working toward knowing the body. This by no means is a simple act of sharing information that already exists; in deciding what to share and how, they develop a highly visualized language for new typologies of the body.

Embedded in diverse forms of communication and a highly monetized digital economy, the current (mis)information order and its management are matters of politics and power. Some studies have suggested that attempts to fact-check and counter misinformation often do not work. Especially when they rely on the ideal of “informed citizenship.” Making the state the sole arbitrator of all truth-claims in times of crisis, is an equally cautionary tale. As the framing of “preventive self-care” versus “treatment” suggests, misinformation governance often means managing what can count as misinformation.

1. The abbreviation AYUSH encompasses Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, Homeopathy, Naturopathy, Sowa Rigpa, and the more capacious “folk healing” systems. With the election of the BJP government in 2014, the ministry of AYUSH was formed as an independent ministry to promote “plural medical traditions.” Ayurveda, however, stands out in the budgetary and ideological support it receives from the state.

2. I retain the word misinformation in this article to refer to its discursive presence. See Lexicon of Lies for a useful typology for addressing misinformation.

3. Several states like Goa and Kerala have declared adoption of Ayurveda guidelines for patients who have tested positive for Covid-19. No such announcements have been made for other AYUSH-related systems.

4. Not only have the sales gone up, there have been complaints of price gouging by sellers of Patanjali’s Giloy on Flipkart, a popular shopping platform.

5. The National Institute of Ayurveda in its plan of action calls upon doctors to “allay panic and anxiety of the public” but at the same time directs the faculty to “avoid speaking with the media or take the official line in this matter.”

Berger, Rachel. 2012. “From the Biomoral to the Biopolitical: Ayurveda’s Political Histories.” South Asian History and Culture 4, no. 1: 48–64.

Bode, Maarten. 2007. “Taking Traditional Knowledge to the Market: The Commoditization of Indian Medicine.” Anthropology and Medicine 13, no. 3: 225–36.

Kalyan, Rohan. 2020. “Eventocracy: Media and Politics in Times of Aspirational Fascism.” Theory and Event 23, no. 1: 4–28.

Mukharji, Projit Bihari. 2012. “Cultures of Fear: Technonationalism and the Postcolonial Responsibilities of STS.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society 6, no. 2: 267–74.

Nijhawan, Shobna. 2018. “Cumin, Capsules, and Colonialism: ‘Real’ and ‘Imagined’ Medical Encounters in the Hindi Literary Sphere.” Asian Medicine 13, nos. 1–2: 170–97.

Sinha, Amber. 2019. The Networked Public: How Social Media Changed Democracy. Delhi: Rupa Publications.

Stalcup, Meg. 2020. “The Invention of Infodemics: On the Outbreak of Zika and Rumors.” Histórias of Zika, Somatosphere, March 16.

Subramanium, Banu. 2019. Holy Science: The Biopolitics of Hindu Nationalism. Seattle: University of Washington Press.