Burning through History in California’s “Asbestos” Forests

From the Series: Firestorm: Critical Approaches to Forest Death and Life

From the Series: Firestorm: Critical Approaches to Forest Death and Life

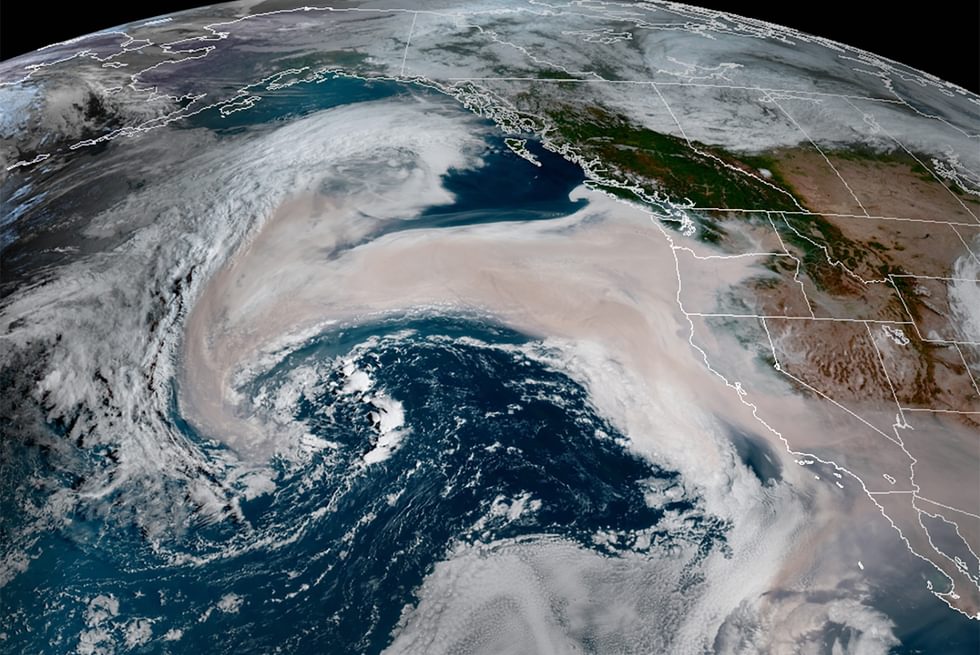

The Mountain View fire began on a cool, windy day in November. Like so many of California’s destructive fires of late, its proximate cause was wind-damaged electrical equipment. Abetting this were the abnormally dry conditions that left plants and their parched soils susceptible to combustion. In the span of a mere twenty-four hours, the flames spread across twenty thousand acres. It burned through shrubs and trees. Then it burned through the pastures and small ranches in the valley. Even those places close to town were not safe from the flames.

Before the fire was put out by rain and snow, it had claimed the life of Sallie Joseph, a beloved local poet. It destroyed ninety homes, leaving one hundred people homeless. The community lost the Toiyabe Indian Health Clinic, serving Native American residents–largely Paiute and Washoe people—of Mono County and neighboring Nevada. This loss left Indigenous residents to drive 125 miles for health services in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic when rural caseloads were near their peak.

This is a landscape defined by epochal destruction, one connected to a deep history of colonial violence. Early foresters referred to the Eastern Sierra Nevada as “asbestos forest” because it was believed they were incapable of sustaining a large conflagration. Yet the landscape that early settler foresters encountered in California’s Sierra Nevada at the beginning of the twentieth century was hardly an untouched Eden. Instead, it was a landscape that saw millennia of careful Indigenous stewardship followed by a harsh period of unrestricted livestock grazing that radically transformed the region’s plant and animal life.

Antelope Valley is situated on the arid eastern fringe of California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. It is defined by the importance of water. The West Fork of the Walker River wends its way through the valley, swelling to cover fields in the spring before gradually drying to a shallow ribbon of water in the fall. The valley is home to three small towns—Walker, Coleville, and Topaz—and nearly one-quarter of the valley’s estimated 1,450 residents are Native American. The area is home to many working-class families tied to an economy dependent on local government and the service industry. The poverty rate is significantly higher than the statewide average, and like many rural areas, housing is difficult to come by.

The tragedy of the Mountain View fire encapsulates the unequal burdens of fire in rural California: those whose social and economic status make them most vulnerable are least able to mitigate its impacts. Native Americans and non-Indigenous working-class residents are among the most vulnerable communities, as this fire revealed. The high cost of building retrofits are a significant barrier to many home owners. Additionally, many residents are reluctant to move from places where they have lived most of their lives. As for the larger forces at work, there is little local residents can do about how distant electrical utilities maintain their equipment or how the federal and state governments manage forests on public lands.

These vulnerabilities reveal the close link between the health of forests and the well-being of communities. But more than just material needs are the deeper senses of loss these fires create—the loss of culturally important landscapes for Indigenous traditional foods and practices, the loss of rural social identities tied to now destroyed family homes and ranches, and the loss of a sense of belonging when there appears to be no place left for one to stay.

The past eighteen years in the U.S. Southwest have been drier than any other period in the past five hundred years. While eastern Sierra Nevada forests are uniquely adapted to drought due to their long endurance in an already variable climate, this stretch of dryness has been visibly wearying for forest communities. Ever since the assertion of U.S. federal control over forests in the early twentieth century in the Eastern Sierra Nevada, fire suppression has been either explicit or de facto policy (Pyne 2016). Even when the fire suppression policy of the U.S. Forest Service was officially ended in 1970, fire suppression continued as a de facto practice because the service is tasked with protecting property. The great post-war infrastructure boom saw extensive development within forests—sometimes on extant private property inholdings and other times as recreational facilities or road and trail infrastructure that lock in a policy of fire suppression in all but the most remote lands.

While fires that did not threaten life and property are now left to burn out when declared low-risk, most of these locations are deep within undeveloped areas, such as the high country of Yosemite National Park, and not where fire is needed most to regenerate forest health. It is critical to recognize that today’s forests are an ecological product of settler colonialism: they resulted from Indigenous land dispossession and the suppression of knowledge and practices of stewardship that used fire as a tool to shape forests.

Federal land managers face complex bureaucratic barriers to expanded use of fire—liability for prescribed fires that escape control, air pollution restrictions, and the resources to carry out these labor-intensive projects. An undervalued approach to address these challenges is a greater role for Indigenous nations as stewards of these lands with a history of using fire as well as their status as fire-vulnerable communities with an essential stake in healing landscapes from past land management practices.

The “asbestos” forest turns out to be an ironic metaphor given these forests are actually highly flammable under settler colonial management practices. The story of the Mountain View Fire in Mono County is the story of much of California—of landscapes whose most successful stewards were driven from the land as settlers took possession of it. These acts of violence also suppressed the knowledge and practices that promoted more resilient forests under Indigenous stewardship.

The long-term necessity of empowering cultural burning is inextricably tied to the political struggles of Indigenous nations. The return of dispossessed lands and the foundation of a meaningful partnership in stewarding their ancestral homelands, now largely under the management of U.S. federal agencies, is urgently needed to address more than a century of fire exclusion.

Indigenous communities still occupy and call these lands home and are among the most vulnerable in facing the enduring impacts of settler colonialism on forest management. A fire does not end when the flames are out. It is merely another phase change—one that marks the beginning of community recovery. It is a process of repair that not only involves stewardship of forests, but also protecting the communities who are most vulnerable from the risks of future conflagrations.

Pyne, Stephen J. 2016. California: A Fire Survey. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.