Changing Definitions of Autochthony and Foreignness in Bangui

From the Series: The Central African Republic (CAR) in a Hot Spot

From the Series: The Central African Republic (CAR) in a Hot Spot

There are many people who had not heard of the Central African Republic (CAR) before the outburst of the recent conflicts there. Some might remember the over-indulgence with which Bokassa, at the end of the 1970s, proclaimed himself Emperor of his Central African Empire. Today the royal chair used for Bokassa’s crowning stands outside the dilapidated hall built for the occasion, covered by weeds, with its diamonds, gold, and glory long since torn from it.

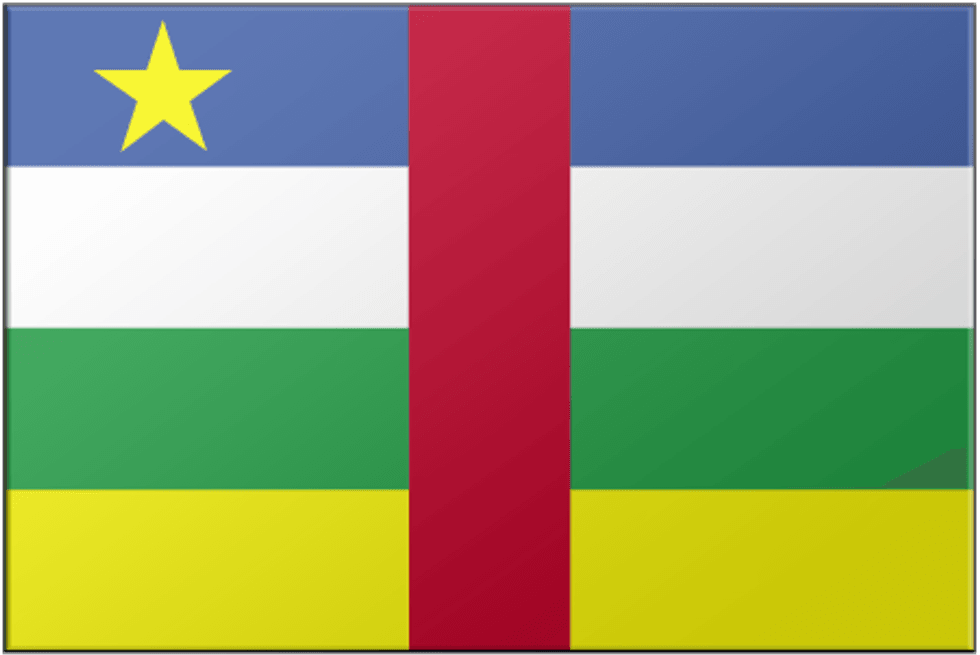

In the last couple of months, the CAR’s usual oblivion from the perspective of global media has turned into another wave of attention to “barbarism” and exceptionality. This time it was not opulence and corruption, but political chaos and inter-communitarian fighting that drew the media’s eye. In the news overload we have witnessed in the last couple of months, the crisis seems to have brought about one positive thing, some argue: the common man is at least able to point CAR on the map of Africa (which is not so challenging given its name, the Central African Republic, or Be-Afrika, literally the heart of Africa in Sango, the local language).

By using words such as genocide, interreligious clashes, and ethnic cleansing, the news items on international news websites and social media pages did not pass unperceived. But what do these terms actually mean? I agree with the analyses of Louisa Lombard and Alex de Waal, that overstating and misdiagnosing the situation risks obscuring a thorough understanding of the conflict in CAR, especially as there is not a single victim side. Thus genocide, interreligious clashes, and ethnic cleansing are part of a discourse that advocates international military action. The French Sangaris forces entered the country in late November 2013, following a media offensive that featured the term (pre-)genocide. A month and a half later, the term genocide popped up again, preceding the call to launch an European military mission as well as the United Nations decision on whether to send troops or not.

Even if one cannot deny that the fighting has a religious edge to it, the core of the problem is not religion. As the Seleka stepped up to the capital in March 2013, their target was to depose former-president Bozizé, a political and not religious goal. It is not my purpose to describe how the conflict turned religious. The conflict could just as well have been between different ethnic groups, had the cards been played differently. The surge of violence remains a translation of the same root causes: a mix of political opportunism and an omnipresent feeling of mistrust of the foreigner, set against a background of poverty and lack of opportunities.

Foreignness is a slippery concept that switches meaning every time the political setting changes. In a context of political instability, mistrust attenuated by concerns over foreignness can urge individuals to keep up exaggeratedly friendly attitudes (attitudes that would feel misplaced otherwise) in order not to be accused of being the foreigner. In CAR, this type of ingrained, yet always changing, mistrust has accumulated in a snowball effect of personal revenge and counter-revenge, where individuals misuse the chaos in order to further their own interests.

At least since Djotodia took power in 2013, the Northerner stands as a synonym for dangerous foreigner, whether s/he is legally Centrafrican, Chadian, or Sudanese. But Northerners are not the only “dangerous foreigners” in CAR’s history. Just over a decade ago, in the political context of the time, that label was reserved for some of the Southerners, especially the nationals from DRC, often described as the Banyamulenge. Banyamulenge was the name given to the Congolese troops of Jean-Pierre Bemba, the rebel leader who was brought in by Patassé to fight Bozizé’s troops, who were backed by Chadian president Idriss Déby at the time. Not unlike the Seleka, the Banyamulenge caused a lot of havoc in Bangui in the early 2000s. Bemba and his troops were chased out, but the name remained and their bad reputation fell on the Congolese-Centrafricains, the foreigners at the time. Yet being Congolese does not necessarily imply foreignness; the river that separates the two countries can be viewed as a contact zone more than a division line.

Foreignness brings with it another loaded concept, that of autochthony. To me, Bangui felt like a city built up of “only” foreigners. Many residents immigrated from elsewhere, or their parents did, looking for trade opportunities; others have their roots on both sides of the Ubangi River, playing with a double nationality; there are also those born out of mixed roots. In the past decades, Bangui has received waves of refugees and migrants from the North (Chad and Sudan) and the South (both Congos), but also from further-away countries like Rwanda.

Borders are porous; people move and intermarry. What does being a Centrafrican mean? The meaning of autochthony shifts as political alliances shift, and the foreigner becomes the prey in this shifting. Viewing the conflict in terms of foreignness helps us to look beyond the religious discourse projected onto the conflict and to understand it from a historical perspective. The root is mistrust, expressed in foreignness, exacerbated by poverty and ignited by (personal) political agendas.

Looking at it from a wider perspective, the conflict should encourage the international observers to reflect upon and rethink what a foreigner is, but more so, to reflect upon the meanings of borders and mobility across borders when placed in the dialectics of the nation-state. It shows the limits of this political construction and encourages us to develop new frameworks that can encompass mobility, porous borders, and mobile individuals, and which are not organized around autochthony. The rethinking of a new model would not only be useful in Africa but also across the globe.

But let me return to Bangui. It is true that in dire times fears of foreignness can feed mistrust. But a mixed society can be a strong society. Is Bangui still the cosmopolitan city it used to be? The Muslim population has mostly been removed, but is the rupture irreparable? When a door closes, another one opens. Is this conflict a door-opener to other groups of people? Who are they? And what will happen to those who left, those who were the economic spine of the country? Will they come back? All of these questions, and many more, remain.