This Hot Spot is dedicated to Dennis D. Cordell, whose generosity and example nourished a number of us as we came to know CAR, and who passed away far too soon.

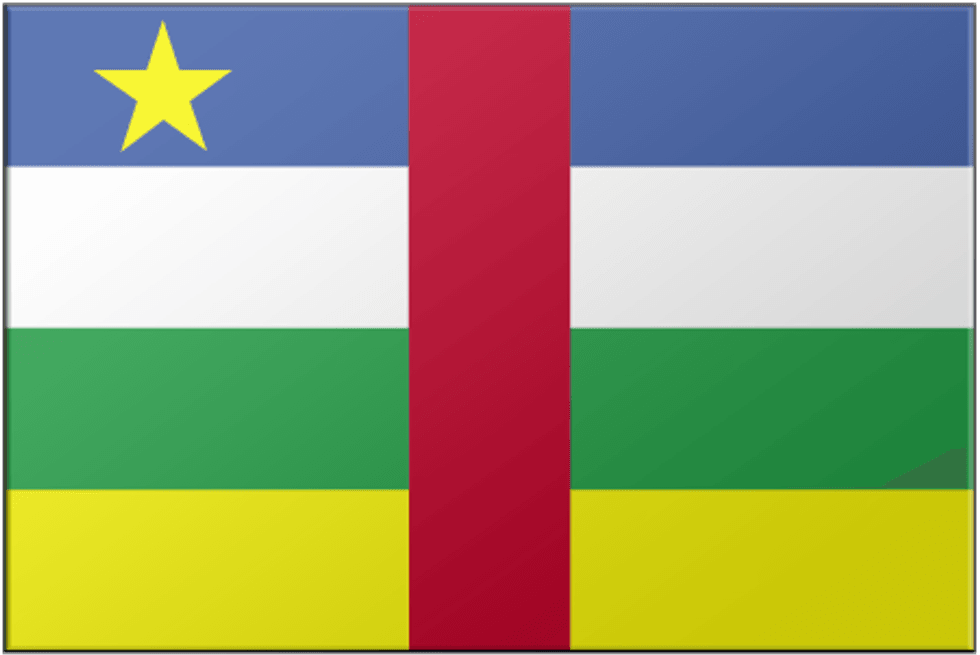

In a multitude of ways, violence in the Central African Republic (CAR) has engulfed everyone in the country over the past year. It has also drawn increasing attention from international news media and diplomats, who have often represented the violence in misleading ways for the sake of advocacy or simplicity, as Marielle Debos describes in her essay. Calculating that it would be difficult to capture the attention of a jaded and over-extended international community, diplomatic and media-advocacy accounts turned quickly to their most powerful rhetorical tool— genocide—to force people to care about a classically out-of-the-way place. In this Hot Spot, scholars with long engagements in CAR offer a range of other reasons to care about “the crisis in the CAR,” to borrow the usual journalistic phrasing. In so doing, they both complicate and clarify the advocates’ picture of destruction.

For those who follow Central African developments closely, the essays in this collection offer ways of making sense of the region’s recent turbulent decades, as well as suggestions as we look ahead. But these essays provide much for those with interests further afield as well, for they also provide nuanced reflections on violence, temporality, empathy, and the anthropological project. In this introduction, I outline some of the essays’ main themes. In a companion piece, I sketch the main trends and events in Central African political history for readers to reference while reading the other entries.

The authors of this Hot Spot’s short essays are united in seeing recent upheaval in CAR as a result of tensions and traumas at once longstanding and fresh, and at once highly localized and reflective of more-widely-spread trends. They also draw out the uncertainty and instability that have come to characterize life in CAR. Tamara Giles-Vernick traces uncertainty through the waves of “cataclysmic violence” Central Africans have experienced over the past two centuries, violence that has been alternately socially remembered and erased. “I wonder, too,” she writes, “whether this ‘forgotten’ past is remembered in other ways, perhaps in the accumulated doubts that have eroded usually taken-for-granted social relations.” Andreas Mehler tracks insecurity through the fates of the country’s small cadre of political elites, who have long operated in a context marked not by democratic sparring but rather by torture and assassination of those deemed not sufficiently in line with presidential prerogatives. Andrea Ceriana Mayneri follows the question of insecurity at a different level, that of Central African conceptions of power and its locus in the body. As subject-participants in centuries of exploitation by people migrating into the area, Central Africans have felt a long impoverishment of their stores of strength, symbolic and otherwise. Spectacular events such as the infamous case of cannibalism in Bangui in January must be understood in this light: as attempts to wrench power back from enemies through the total destruction of their bodies, which are reservoirs of power even after death. For Henri Zana, an archeologist at the University of Bangui, writing with Rebecca Hardin, uncertainty is fast giving way to certainty: staying in Bangui has caused his “professional death.” Yet he remains committed to changing the dire circumstances students and others face in CAR.

Many of the authors emphasize the need to ask questions rather than declare answers. Pierre-Marie David, Cathérina Wilson, and Bruno Martinelli all argue that the time has come for a fundamental rethinking of the state form in CAR. As David puts it, it is necessary to simultaneously accept that knowledge of violence as it happens will always be fragmented while refraining from naturalizing that fragmentation, as if Central African social life is and was necessarily such a frayed patchwork. What, then, are the political and anthropological possibilities beyond humanitarian/military action? In Bangui in 2010, I chatted with a French diplomat who pronounced that the end of CAR as a state was nigh; its various regions would, he prophesized, be swallowed by more-powerful surrounding countries. That prospect seems both more and less likely today. What might the future hold in terms of new geographies of protection and inclusion?

Two of the entries (by Lesley L. Daspit, and by Rebecca Hardin and Melissa J. Remis) pursue this Hot Spot’s themes from another kind of hot spot: the biodiversity hot spot that is the Dzanga-Sangha Biosphere Reserve (or RDS, from the French acronym) in far southwestern CAR, an area that has attracted more researchers than anywhere else in CAR. Hardin and Remis reflect on changes over several decades, now that food scarcity has come to a place once characterized by abundance. They both got to know rural Central Africans deeply and marveled at people’s ingenious techniques for mostly-sustainably reaping abundance from the countryside, producing rich lives from the perspective of their “logic of sufficiency.” Those days have passed, however, as armed conflict has engulfed even this quietest corner of the country.

Some of the authors have been working in CAR for decades and narrate their surprise at the extent of the rapid descent into war, which has captured people from formerly peaceful locales in its logics. Martinelli writes of his difficulty coming to terms with the fact that some of his former anthropology students have joined anti-Balaka fighters and armed themselves both with guns and extremist rhetoric. The progressive withering of the state over the past few decades has fostered discriminatory, when not outright violent, autochthony movements; how might that trend be reversed? Hardin and Zana suggest that one avenue might be through a revitalization of the educational system. Others have come to the area more recently, during the period that CAR has been part of the "global reservation,” as Amitav Ghosh presciently described the post–Cold War, United Nations order of peace-kept places.

Writing as widespread violence remains ongoing presents all of us with challenges that transcend our varied temporal engagements with Central Africans. Ethnography’s insights are a form of hindsight: it is, in part, the time lag created by the duration of researching, writing, and publishing that allows for “making sense” of violence and war, as the anthropological literature on “new wars” in Africa and elsewhere has done, in many cases brilliantly. But violence-as-it-is-happening presents us always with an excess—an excess that might not have a sense to it. Things happen when people have guns and violence becomes widespread, things that might not have been planned or thought through. Literature and memoirs about war have long known this, of course. In the novel-memoir The Things They Carried, Tim O’Brien wrote, “In a true war story, if there’s a moral at all, it’s like the thread that makes the cloth. You can’t tease it out. You can’t extract the meaning without unraveling the deeper meaning. . . . True war stories do not generalize” (57, 59). O’Brien’s statements do not translate easily into social-science research projects. But they do inspire us to think about what solidarity with the war-affected looks like, both as violence happens and during its afterlives.

Posts in This Series

A Brief Political History of the Central African Republic

Central Africans, whose country was once known as the “Cinderella” of the French Empire, have never had an easy time of it. When French colonists arrived at the... More

“Cannibalism” and Power: Violence, Mass Media, and the Conflict in the Central African Republic

The crisis in the Central African Republic is contributing to the reactivation of a longstanding mixture of memories, fears, and resentments among the populatio... More

Stories and Fragments of Violence: The Necessity of Rethinking the State

Since December 5, 2013, images of death and violence have traveled from Bangui through the media of the world, from the official media to social networks. This ... More

“Hate” and “Security Vacuum”: How Not to Ask the Right Questions about a Confusing Crisis

Discourses on the crisis in the Central African Republic have quite confusedly evoked humanitarian and security issues. The two frameworks frequently applied to... More

“Professional Death” and Rebirth? History, Violence, and Education

What is it like to be a Central African anthropologist right now? On September 6, 2013, Henri Zana, an archeologist at the University of Bangui, wrote the follo... More

History, Erasures, and Accumulated Recollections of Violence

Really, the circumstances under which I left Bangui give me insomnia. My house was burned, I don’t know where the mother of my child is, and I didn’t take a sin... More

From Abundance to Acute Marginality: Farms, Arms, and Forests in the Central African Republic, 1988–2014

We mark with near disbelief the descent of the Central African Republic (CAR), a water- and food-abundant country, into a situation where famine risk structures... More

La mémoire de la violence en Centrafrique

2013 fut l’année de toutes les formes de violence et de danger pour les centrafricains. Parvenue au pouvoir, la Seleka instaura un régime de répression qui légi... More

Pathways to Elite Insecurity

Atrocities between neighbours, Christians against Muslims: Central African Republic (CAR) today looks like a perfect illustration of the famous Latin adage “hom... More

Changing Definitions of Autochthony and Foreignness in Bangui

There are many people who had not heard of the Central African Republic (CAR) before the outburst of the recent conflicts there. Some might remember the over-in... More

Losing Paradise: War Comes to a Biodiversity Hot Spot

Though the Central African Republic has witnessed a handful of coup d’états in its postcolonial history, the most recent one, in March 2013, is unlike those in ... More