Citational Politics: On Recognition, Circulation, and Response

From the Series: Being @CulAnth: Social Media as Academic Practice

From the Series: Being @CulAnth: Social Media as Academic Practice

In the political economy of the production and dissemination of knowledge, open access (OA) journals offer the possibility to rethink collective engagement with scholarship (Corsín Jiménez, Boyer, Hartigan Jr., and de la Cadena 2015). OA as public anthropology demonstrates a more ethical and expansive model of knowledge dissemination wherein knowledge is not foreclosed to an audience behind the (pay) walls of academic institutional affiliation. Within seven years since its shift to OA in 2021, “the quality and breadth of Cultural Anthropology’s submissions and the impact and global reach of its published volumes have benefited from its free and open accessibility” (Besky et al. 2021).

In thinking with collective commitments towards accessibility and the ethical possibilities of digital OA and public anthropology, this series writes about the complexities of our responsibilities to disseminate the work of Cultural Anthropology and Fieldsights on behalf of the Society for Cultural Anthropology (SCA). While other sections regularly publish work, our work is the labor of citation. This post thinks with citation as a central praxis for the Social Media Team (SMT) because our primary role within the Contributing Editors (CEs) Program is to circulate and promote the published work within the SCA and its journal. To unmoor citation from its paged placements, how can we think of citation and its formations within the scope of a public social media account for a large professional association? Thinking with citation within the context of the @CulAnth Twitter account also requires thinking through the expressions by which citation is enacted by our current team.

To think with citation, we have to situate citation as a political practice that connects genealogies of knowledge, people, and place. As a political heuristic, citation illuminates the logics that condition(ed) the “production, legitimization, and dissemination of anthropological knowledge” (Leonard 2021, 219) organized along subject positions and power relations. These structures, when critically analyzed, reveal the politics of disciplines that continue to reproduce Western paradigmatic “assumptions, concepts, and theories at the core of the discipline” (Harrison 1999, 6) that render some into the intellectual peripherals of anthropology. These political investments have epistemic and material costs for scholars on the intellectual peripheries of their academic disciplines. In a recent Cultural Anthropology #CiteBlackWomen Colloquy, co-editors Anne-Maria B. Makhulu and Christen A. Smith (2022) and contributing authors Faye V. Harrison, Savannah Shange, and Bianca C. Williams engage in an analysis of disciplinary citation that speaks to the logics and methods of systemic erasure and silencing of Black women anthropologists.

Turning towards the theorization of citation in this colloquy, we situate the possibilities of citation as an everyday practice of collective relationality. For Williams (2022), citation “can be a very active and intentional process of intellectual genealogy and community formation” that calls and connects people through the intellectual, professional, and personal connections that have sustained the work. Writing about disciplinary belonging, Williams emphasizes how critical conscious citational commitment (see also Mott and Cockayne 2017) is to acknowledge the situatedness of the people, conversations, and communities that hold our work and us. In the same colloquy, Shange (2022) resituates “citation as a practice of relation” in meditating with #SayHerName and #CiteBlackWomen as ceremonial practices that name Black women’s presences and value through these digital registers of recognition. Thinking with the more capacious framings of citation theorized here, we frame the modes of citational practices we engage as strategies towards a digital platform situated in the relational webs of scholarship that are attuned to the politics of recognition, circulation, and response.

The website for the SCA houses its flagship journal, Cultural Anthropology and Fieldsights. Fieldsights is a short-form web publication that includes interventions across a range of media composed of the Editor’s Forum and Contributed Content. The Editor’s Forum features essays reviewed by Cultural Anthropology editors that bring together scholars across institutions and career stages. Contributed Content is often written by early career scholars in the SCA’s Contributing Editor (CE) Program and range across media like the podcast AnthroPod, insights from SCA members in Member Voices, resources for teaching in Teaching Tools, Supplementals to expand on Cultural Anthropology research articles, and the multimedia forum Visual and New Media Review.

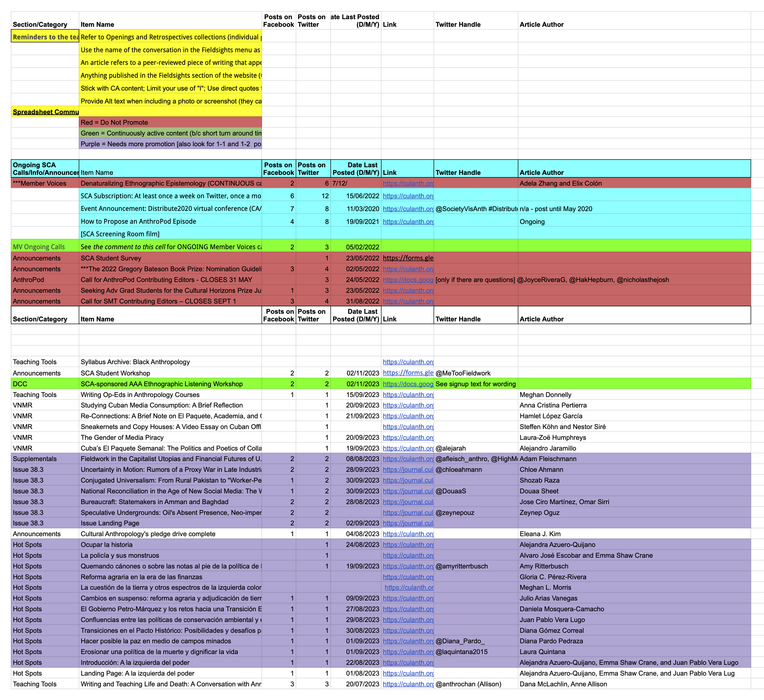

When there are new publications in the journal or Fieldsights, materials are documented in a Google spreadsheet shared and populated by SMT members with archived publications since 2015. To think of this spreadsheet as collective documentation wherein citation is engaged, we turn toward the mechanics of documentation: To be very serious about curation and citation is to make lineages and histories of ideas more apparent or conspicuous. In our work as handlers, we have the task of representing the work of the journal and Fieldsights authors and ensuring there is continuity and rightful representation of the work between website publication and social media. Ensuring that an author is receiving due recognition includes tactics such as correlating their social media handles and creating those links in account posts.

The spreadsheet contains a column per each of the following items:

In addition to the data of each publication item, the spreadsheet includes a color key that aids in communication between handlers as the accounts are circulated across the team. This key is composed of four colors: red, green, blue, and purple. When highlighted in red, items are not to be promoted. This most often occurs when items reach deadlines (such as calls for submissions) but can also be marked red if the Society communicates to handlers to cease the promotion of particular items. Green items are marked as continuously active content because of their short timeframe on the website (such as film screen series from the Visual New Media Review or calls for submissions). Blue items are ongoing items with calls for submission or participation with no noted end date (such as the SCA subscription). Purple items are marked when materials have not been aptly promoted on the accounts yet. When outgoing handlers transition the accounts to the incoming handler, we often include a synopsis of our noted observations, weekly events, and experiences on the accounts, as well as an updated spreadsheet. The spreadsheet functions as a collective form of documentation amongst handlers as we update it when new content is published and when any content is posted on the accounts. It is also the place we return to in search of publications that can speak to the current moment.

This latter point speaks to the invisible labor we do as handlers when sifting through the archive to locate and recontextualize older pieces, putting them into conversation with the present. We experience handling the accounts when the rupture of a major event ripples across social media platforms as users respond, gather, and even mobilize. In some instances, we find it inappropriate to share content from our own archives and instead opt to re/tweet and share resources, information, and funding pages from those impacted. In other instances, there is space for situating scholarship published within the SCA and its journal, whose work can inform, give description to, and theorize the contemporary moment. This collective document allows for an enacting of older citations, bringing the pieces and authors back into the conversation.

In the last two years, we asked authors to submit their handles to the journal editorial team and CE program coordinators. Doing so bolstered the digital connections between published journal and Fieldsights material and the online accounts of authoring scholars and collectives as we were able to include handles more frequently in posts. We imagine that @-’ing is a practice of naming and thus recognition that creates connections not only between authors and publications but also for others to follow and connect with scholars in similar professional and research areas. Part of why we decided to ask the editorial team for handles is also because we recognized the potential risk or harm involved in tagging an author without their permission. Being tagged on such a large account can no doubt bring about (un)wanted attention for a Twitter user who may not be prepared to manage that attention, directed dialogue, or the inevitable retweeting, @-’ing, and commenting. As an ethical practice, including handles is about recognition, but we are also mindful of what recognition and attention might mean in a public-facing environment.

Being a handler is shaped by the expectations and ethics of an anthropological community and our own politics. The @CulAnth account as an interface is partially composed of our own and past handlers’ engagements with and through the account. As such, the account is not a stagnant interface where handlers input content, press send, and move on. In our engagements as handlers, we react and respond to ongoing sociopolitical events as they unfold and find impact on the material lives of people. This section thinks with the particular strategies we engage in crafting a collective and engaged space that maintains the account as an active facet of public anthropological scholarship. Continuing to think with Williams (2022) and Shange (2022), the strategies of citation here are ones in which we weave together connections in material, academic scholarship, and sociopolitical context and invite others to do the same.

“In our engagements as handlers, we react and respond to ongoing sociopolitical events as they unfold and find impact on the material lives of people.”

By weaving tweets together in a thread, threading as a strategy creates the possibility for handlers to weave together conversations across thematics and time. We’re thinking of weaving here as a method of relation that links individual pieces into broader conversations that are situated in crafting connections across research areas, scholars, ideas, and impact. In some of our conversations, this practice of weaving is a practice of cultivating particular conversations and discourses in the recognition of ongoing events. It is not only that we want the @CulAnth accounts to be engaged in the discourses and events at hand, but that we, as handlers, feel the responsibility to engage. Sometimes this looks like threading information, and in other circumstances, it is more useful, ethical, and necessary to retweet the posts, sources, and accounts of implicated and impacted community members and collectives.

In the fall of 2022, scholars on Twitter illustrated this mode of engagement by threading together critical research by scholars of sex and sexuality in response to the publication and widespread circulation on Twitter of an unethical article. The @CulAnth thread was a compilation of threads by other Twitter users in response to the article. The work of citation here was the gathering of these dispersed threads across #AnthroTwitter and #AcademicTwitter into a place that could amplify the ethical and critical work of scholars. The thread also invited other academic Twitter users to add additional works responding to the theme. In other instances, we weave Cultural Anthropology and Fieldsights sources together, such as this New Year’s Eve 2020 thread that compiled the most-read pieces in 2020. This thread spanned across publication years, journal issues, and member-contributed publications, from Joseph Dumit's 2014 article “Writing the Implosion: Teaching the World One Thing at a Time” to the April 2020 COVID-19 series. Sometimes, SMT members collectively feel the resonances of these threads as graduate student workers and as committed to the struggles for workers’ rights: During the #UCSCStrike, the demands for a Cost of Living Adjustment (#COLA4All) reverberated across #AcademicTwitter and our own team. This model, as we expand on in Invisible Labor (this series), is not distinct from our positions as underpaid and undervalued across universities and departments. Even more so, one of our own team members was impacted by the University of California, Santa Cruz's dismissal of graduate students. In response, and with our position to leverage social media accounts to support striking graduate students, we created a thread to bring attention to the strike, retweeting financial resources such as GoFundMe pages, and amplifying the voices of impacted graduate students.

While not attended to here in-depth, live-tweeting (expanded on in this series) is also a practice of citation we enact. At disciplinary conferences like the American Anthropological Association (AAA) and the most recent and jointly hosted Virtual Otherwise by the SCA and the Society for Visual Anthropology, the SMT engages in live-tweeting as a practice broadening the engagement with a particular scholar or event. For Distribute 2020, we worked closely with the Distribute team to link the SCA account and activity around the conference. See Live-Tweeting as Academic Practice for more on the politics, approaches, and conceptual understandings of live-tweeting as a practice.

Within Twitter ecologies, the #AnthroTwitter enclave is a co-constitutive space where scholars of anthropology and adjacent fields connect, share resources, give insights, and more. As handlers, we are continuously shaping the discursive space, timeline, and politics of the account. Over the last several years of working together, we have talked through our collective politics, commitments, and responses to ongoing events and strategies for material promotion and circulation. Attuned to the relational production of knowledge, this post endeavors to detail the logics and strategies that guide our engagements as handlers for @CulAnth and the SCA.

Besky, Sarah, Ilana Gershon, Alex Nading, Christopher Nelson, Katie Nelson, Heather Paxson, and Brad Weiss. 2021. “Opening Access to AAA’s Publishing Future.” Member Voices, Fieldsights, June 30.

Corsín Jiménez, Alberto, Dominic Boyer, John Hartigan, Jr., and Marisol de la Cadena. 2015. “Open Access: A Collective Ecology for AAA Publishing in the Digital Age.” Member Voices, Fieldsights, May 27.

Dumit, Joseph. 2014. “Writing the Implosion: Teaching the World One Thing at a Time.” Cultural Anthropology 29, no. 2: 344–62.

Engel, Stephen David. 2020. “Dear President Napolitano: I Am a Wildcat Striker and We Will Win.” The File Mag, February 26.

Harrison, Faye V. 1999. “Anthropology as an Agent of Transformation: Introductory Comments and Queries.” In Decolonizing Anthropology: Moving Further Toward an Anthropology of Liberation, edited by Faye V. Harrison, 1–15. 2nd ed. Arlington, Va.: Association of Black Anthropologists and American Anthropological Association.

Leonard, Wesley Y. 2021. “Toward an Anti-Racist Linguistic Anthropology: An Indigenous Response to White Supremacy.” Linguistic Anthropology 31, no. 2: 218–37.

Makhulu, Anne-Maria B., and Christen A. Smith. 2022. “#CiteBlackWomen.” Cultural Anthropology 37, no. 2: 177–81.

Mott, Carrie, and Daniel Cockayne. 2017. “Citation Matters: Mobilizing the Politics of Citation toward a Practice of ‘Conscientious Engagement’.” Gender, Place & Culture 24, no. 7: 954–73.

Shange, Savannah. 2022. “Citation as Ceremony: #SayHerName, #CiteBlackWomen, and the Practice of Reparative Enunciation.” Cultural Anthropology 37, no. 2: 191–98.

Williams, Bianca C. 2022. “Black Feminist Citational Praxis and Disciplinary Belonging.” Cultural Anthropology 37, no. 2: 199–205.