Conclusion: Overtaken by Events

From the Series: Teaching about Rape in Troubled Times

From the Series: Teaching about Rape in Troubled Times

Teaching is a learning experience for instructors as well as for students. As we went through the “Gender, Violence, and Culture” course with our students, the teaching staff checked in with each other to reflect on what we thought our students were learning and what we were learning from them. The intensity of our classroom experiences, combined with the increasingly obvious connections between the course and the 2016 election, prompted us to wonder about the relationship between pedagogy and political action. The students’ final papers, invested with both personal angst and political questioning, inspired us to begin the discussions that resulted in this series of posts.

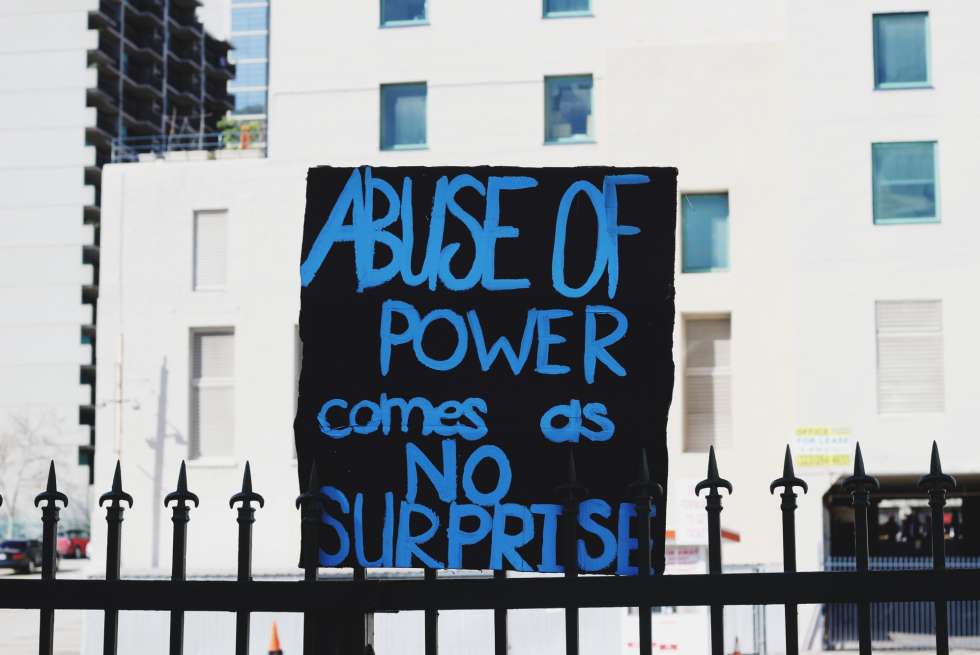

Little did we imagine how quickly our writing process would be overtaken by events. As discouraged as we and our students had been by the results of the November election, none of us could have foreseen that Charlottesville and the University of Virginia (UVA) would become a site of white-supremacist political action. As has been widely reported, white supremacists, many of them heavily armed, descended on Charlottesville on August 11, 2017 to protest the removal of statues of Confederate war heroes from public parks and to make a show of force that would intimidate their opponents. On the eve of their scheduled August 12 protest, hundreds of them, bearing lighted torches, marched to UVA’s central grounds where they chanted racist, anti-Semitic, and homophobic slogans and assaulted students and staff who tried to stand up to them. The university police had not been mobilized to respond to this event and arrived only after it was over. The next day, the violence was worse, resulting in the death of one counterprotester and many serious injuries when one of the white supremacists rammed his car into the crowd.

Student and community activists were deeply disturbed by the actions of the city government, local police, and the university administration preceding and during these events. After much prodding, UVA president Teresa Sullivan established a working group of top administrators “to identify the next steps in the University’s response.” The initial statements of this committee were focused on “the security of the university,” with a promise of greater police presence and a review of “policies regarding activities that can be constitutionally proscribed on our grounds.”

The student response was much more vigorous. It called not only for short-term measures to ensure the security of students, faculty, and staff and to proscribe hate speech and intimidation backed by the threat of violence, but for a thorough reimagining of the University’s historical identity. This will be difficult at an institution whose brand is Thomas Jefferson. People will have to learn to take seriously the negative side of that legacy, as captured in the expression that one of our students used: “racist rapist Thomas Jefferson.” Perhaps the fact that, as we write this, our students are in the forefront of the political movement to change our university should give us grounds for hope that action is possible. And, as our students engage politically with their university, they may find that discussion, argument, and engagement with institutional stakeholders cannot but be a social (and socially constrained) process, despite the fact that their interlocutors are individual human beings.