In the summer of 2020, we faced a challenge (one of many collectively shared): what to do with our general education Introduction to Cultural Anthropology classes, with more than one hundred students, at James Madison University as we faced the truth of them being entirely online. We confronted questions over not only what we should teach in a moment of overlapping crises (an ongoing pandemic, uncertainty over public health safety on college campuses, and the backdrop of increasingly public movements for racial justice), but more importantly how we should teach it. While each of us spent hours researching online course design, we lacked a model for large undergraduate classes (without TAs) that balanced the interactivity of a shared in-person community with the accessibility and engagement of an asynchronous class. After reviewing course design scholarship online and in journals, we found most models focused on smaller discussion-based classes or, for large classes, they assumed that students learning online in fall 2020 had the same pedagogical needs of traditional online learners or should digitally replicate a large lecture room experience, or they addressed specific needs arising out of the spring 2020 pivot online.

We decided on an asynchronous design to meet concerns about students’ high-speed internet access and the pedagogical soundness of teaching a MOOC (massive open online course)-style synchronous lecture. Further, we were interested in and willing to take on reimagining the class to meet our and our students’ needs for both community and manageable workloads. We prioritized first year students' need for community in a brand new environment by centering an ethos of collaboration in both our pedagogical design and their learning experience. We also wanted a class that didn’t feel stale or anonymous when it was taught again (Megan’s teaching it again at the moment). Designing this class together was work (which we discuss below), but delegating content production left us more time to integrate responsive and interactive features (for example, open ended and creative assignments).

Designed for Collaboration

We designed for collaboration in two key ways: 1) our transparent collaboration demonstrated the dialogic quality of anthropological processes, and 2) students’ collaboration built ties in an ephemeral classroom. We maintained this collaborative sensibility by grounding the course in our prior teaching and sharing the work of creating additional pedagogical content, but each grading and advising our own students.

What became our favorite part was the “summary discussions” that ended the weekly module. Across each week, students were assigned a variety of multimodal materials (podcasts, video lectures, documentaries, and more), and while their logic and themes were (mostly) apparent to us, we needed a dynamic way to communicate connections to students. Toward the end of each week, the two of us would sit down on a Zoom call, loosely discuss a structure, and then hit record. For the next twenty minutes or so, we chatted about the key takeaways of the materials, why we each love and insist on covering topics the other may be uninterested in, and how to extend what students learned about these concepts and ethnographic settings to something a little closer to home. During the sessions, we laughed and we thought out loud together. We managed to feel a little less isolated from our collegial worlds and to step outside of the constant pace of producing content for Canvas (our campus’s learning management system [LMS]). For our students, these recorded sessions were a window into our friendship and to the dialogic quality of intellectual life, and also into our pets and our not-so-secret tiktok delights. They allowed us to bring our mass of students into what ultimately felt like very intimate intellectual interactions.

“For our students, these recorded sessions were a window into our friendship and to the dialogic quality of intellectual life, and also into our pets and our not-so-secret tiktok delights.”

While we felt a sense of community by recording these weekly discussions, we still wanted our class to give students a more tangible sense of community—with an eye toward providing our first year students a few other students with whom they could chat, exchange study tips, and be accountable. Students were divided into randomly assigned project groups at the end of Week 3 when students could no longer add the class (with smaller classes we might have been more deliberate in mixing up students from different years). Over the semester, these project groups completed four building block assignments, where in each assignment, students first complete an individual assignment and then work together to complete a collective task (to keep it fresh we incorporated multimodal submissions including video and or audio conversations and culminating in a creative assignment). These were low-stakes opportunities for students to explore how to apply anthropology

We built accountability into these assignments by requiring students to complete the individual assignments five days before the group assignment and by requiring the students to adopt a role (notetaker, team leader, submitter, freeloader) and to rotate roles each week (see examples of individual and group assignments below). Requiring notes allowed us to monitor the progress of groups (and flag students who were checked out of the process). It also allowed us to gauge the effectiveness of the groups as a community-building practice. Over the semester, we began to see some of the topics we joked about in our weekly discussions embedded in their notes. We told students that they could kick out “free riders,” but only after first meeting with us to discuss group dynamics. Notably, no group has exercised this option and students even reached out to us to cover for absent group members (a sign that accountability was not just about productivity, but also care).

These two key components of the class, while not replicating the embodied experience of in-person sociality, allowed us to foreground an ethos of collaboration and community building and to stave off the isolation and anonymity of large-scale teaching and learning in a pandemic.

What It Looked Like

Leaning into the online format, we incorporated an array of multimodal materials in each module—modules were used as a thematic unit to organize weekly topics. We kept a rough balance of two short readings, short recorded video lectures (usually ours, but also teaching videos others generously share online, like Robert Borofsky’s series on Vimeo), and a podcast, documentary, or other multimedia (like those found in the New York Times’s Op-Docs series). We organized these materials into weekly modules, using an introductory page to “unpack” the key terms and ideas that connected the various components and used short ten-point weekly quizzes to gauge students’ comprehension levels (in place of higher stakes formative assessments).

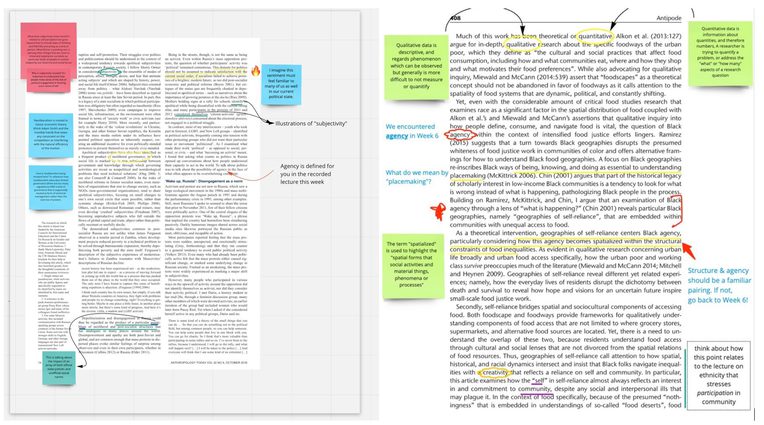

Because the course was asynchronous, we missed the ability to walk students step-by-step through challenging readings or unfamiliar genres (from experience, many students struggle to read a Cultural Anthropology article without some genre scaffolding). To get them used to reading ethnographic writing we adopted Julia Kowalski’s Arrival Stories assignment that forced them to engage with issues of methodology, argument, and authorial voice. We used the online collaborative whiteboard program, Miro (a program we were already using in other classes, which is functionally similar to Google’s Jamboard), to annotate articles for students. Miro allowed us to deconstruct articles by identifying key points and link them to additional resources (in other words, to create an academic form of VH1’s classic “pop up videos”). This approach differs from a program like Perusall, where students annotate collaboratively (though these programs offer alternative ways to address this issue and often are integrated into a school’s LMS).

In lieu of an exam-based final, we adopted the popular unessay format, although there were only a few examples out there addressing the experience of unessays in large, introductory courses (see Contois 2019 and Denial 2019 for examples of unessay guidelines, activities, and grading rubrics). Our goal for the unessay was to have students collaboratively design something that synthesized the key takeaways from the class, but we had to consider the possibilities and limitations of what they could do in groups because most of the examples available were individual student projects from the “before times.”

During the second semester, when only one of us was teaching the course, we kept the course feeling fresh by having the active professor record very short pre-summary videos, similar to our joint summary videos, which drew on current examples to extend those from the prior semester to continue this sense of an active learning community. How to keep future iterations of the course dynamic is an issue we will continue to wrestle with.

What We Learned

We learned more than we anticipated from each other about how each of us teaches and considers the “anthropological project,” as well as from our more than three hundred students enrolled in our courses under tough circumstances. This experience helped us envision how we can change our in-person classes when life returns to “normal,” including how to design meaningful opportunities to practice anthropological concepts in large-scale classes.

Students most enjoyed the group activities that offered up creativity and true collaboration, especially the “create a ritual” assignment (where we received many tongue-in-cheek rituals focused on COVID-19 prevention and workload relief) and “create your own slang term” which we adapted from Wesch's Word-Weaving challenge (see Wesch’s 10 Challenges page for the full list of challenges). The group portion extended his model, requiring each student to submit audio and/or video “evidence” using the word in context and then collectively reflecting on what it takes to both create a new word and to successfully incorporate it into the lexicon.

Given that we usually use exam-based assessments, one of the true joys of this semester was discovering that the implementation of project-based assessments garnered a more holistic assessment of students' grasp on anthropology—and did not burn us out, surprising given the number of students. This was particularly evident in their final, an unessay, where they responded to the prompt: “How would you explain or present the TL;dr of cultural anthropology to next year’s incoming first year class?” We were amused to learn that most of our GenZ students had no idea what “TL;dr” meant; for those of you also not overly online, it’s “Too Long, didn’t read.” The variety of assessments also helped us see how various students shined with the different assessment tools. Students appreciated the flexibility of the unessay format over a traditional exam or paper. We managed the workflow by requiring students to submit an individual proposal (including source list) in Week 13; groups had another week to deliberate about each of the proposed projects before selecting a collective project. We weighed in with audio comments only after this final deliberation, and these final projects were due during exam week. Giving them a rubric with the assignment details both simplified quantitative grading and kept them on task in the face of an unfamiliar assignment genre.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing for us. Having taught three classes across two semesters, the fall 2020 and the spring 2021 experiences were different. Students appeared more overwhelmed by the workload in the spring, mirroring what we’ve found in our other spring classes. While the majority of groups worked smoothly, we had to use the mechanisms to split groups apart when they weren’t working. Similar to the fall, the initial communication between the groups for the first assignment was a struggle to finesse because our LMS is set up so students cannot directly email one another. We’ve tried several options, including asking students to use the group announcements or discussion board features to share contact information (and many groups ultimately moved off the LMS to platforms like GroupMe), but managing group communication and logistics continue to be a challenge. In the spring, we had more groups report challenges, and while no one kicked someone else out, a few students have requested to move to a different group.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing for them either. Students struggled throughout the year due to COVID-19 disruptions, but our choice to allow them to complete individual assignments and quizzes up until the end of the class offered them a cushion for when life happened, and hopefully reduced stress around fixed deadlines (although most students got their work in on time most of the time; less than 5 out of 230 students turned in overdue assignments at the end of the fall semester). Sharing the responsibility for this class between the two of us gave us more latitude to offer latitude to our students.

“It wasn’t all smooth sailing for us . . . It wasn’t all smooth sailing for them either. Students struggled throughout the year due to COVID-19 disruptions . . . ”

What We Suggest

Overall this was a positive experience, yet there are pros and cons of working together this way. Working this closely with someone while developing a class requires a commitment to blend different work styles, habits, and schedule expectations. It requires a commitment to equitable distribution of the workload, although we were each able to cover for the other as needed (whether that was moving material into course pages or sending out notices when the other’s internet was knocked out). It requires commitment to putting the work in on the front end of course planning, and to work one week ahead as asynchronous design demands.

We see no reason why this model can’t work when collaborating with colleagues across institutions. The majority of materials for this course were created outside of the LMS (including our work plan, shared reminders, task list, lecture videos, weekly announcements, and assignments). Because the summary videos brought us so much joy, we suggest incorporating informal conversations with friendly colleagues as an easy way to avoid burnout teaching asynchronously online. This model emphasizes that asynchronous interactivity doesn’t just require faculty to student dialogue, instead integrating informal and informational conversations with colleagues that are directed at undergrads can be a way to create that dialogic feeling in digital spaces.

Sample materials from Rebecca Howes-Mischel and Megan Tracy’s Course:

Cultural Anthropology Syllabus (from the 2021 version of the class taught by Megan)

Individual Activity #1: Observe a Ritual (which pairs with Group Activity #1: Create a Ritual)

Individual Activity #2: Create a Word (which pairs with Group Activity #2: Use a Word)

References

Contois, Emily. 2019. “Teaching the Unruly Unessay.” May 10.

Denial, Cate. 2019. “The Unessay.” Cate Denial (blog), April 26.