Culture and Ethnography in Understanding the War in Ukraine

From the Series: Russia’s War in Ukraine, Continued

From the Series: Russia’s War in Ukraine, Continued

Wars are political, violent affairs that polarize and traumatize. Flows of information are threatened by censorship from above, polarization from the middle, and self-censorship from below. As Eric Leed has observed, if the first victim of war is truth, its second victim is ambiguity. One way to describe the result is a black-and-white photo with no shades of gray. It should go without saying that the white represents “us,” the black is our enemies.

Ethnography can help to restore ambiguity and nuance to understanding war and its consequences. We have a professional duty to understand (although not necessarily sympathize with) diametrically opposite views, not only about the war but also about Ukrainian culture and history. At the extremes, these include Russophobe calls for vengeance on one side, and widespread Russian support for the invasion of Ukraine on the other. Given the challenges of fieldwork during times of war, many foreign scholars will likely resort to remote tools and end up with some kind of chatnography where old acquaintances are engaged online. For many of us, this became a natural response after the news of the war in Ukraine broke out and we sought to hear from people we have worked with for years, and whom we—in many cases—consider friends.

From such communications, what we already know is that mere days after Russian forces assaulted Ukraine, it became clear that Russian strategy was based on a flawed understanding of Ukrainian culture and politics. Russian decision makers had grossly underestimated Ukrainian resistance to an invasion. Combined with the overestimation of Russia’s own military capability, that resistance meant that the Russian attack soon stalled.

During the month that preceded the invasion, Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) conducted survey research in Ukraine to gauge the political temperature among Ukrainians. According to the results, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy possessed a rather lukewarm 34 percent approval rating. Forty-four percent of those polled expected to have trouble paying utility bills. Forty percent stated that they would not defend Ukraine if the country was invaded.

The survey results may have reinforced a pre-existing notion that Ukrainians would welcome a regime change—or at least not risk their lives for Zelenskyy’s administration—reinforcing what Russian President Vladimir Putin had previously claimed. In a much-discussed article published the previous July (now mandatory reading in the Russian military), Putin argued that Ukrainians were “really Russians.” Real Russians, one might expect, would at the very least tolerate a new pro-Russian regime, if not welcome it outright.

Claims about culture and history thus loomed large as stated reasons for Russian aggression against Ukraine. When announcing the beginning of his “special military operation,” Putin called Zelenskyy’s government a “neo-Nazi” “junta” and “people’s adversary which is plundering Ukraine and humiliating the Ukrainian people.” Putin thus drew a direct line between the war and the memory politics of the Second World War. His decision to refrain from calling the war a war seems like Orwellian newspeak today, but it may also reflect a genuine belief that Russia would repeat, on a national scale, the swift and almost bloodless 2014 invasion of the Crimean Peninsula. It was hoped a quick operation would limit international response.

However, the Crimean invasion and annexation benefitted from the element of surprise as well as a favorable political situation. The 2014 Maidan revolution exacerbated Ukraine’s existing divisions as Russian propaganda formed new ones. In Crimea, especially, Ukrainian security forces had been unprepared and not sufficiently politically reliable to withstand the invasion.

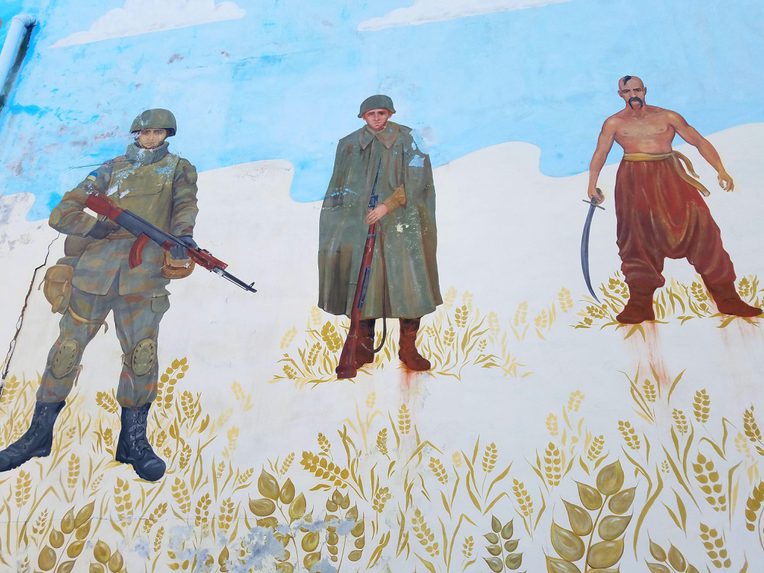

Whereas Russia was able to establish control over Crimea, its subsequent attempts to stir unrest in eastern Ukraine were less successful. The surprise was spoiled. Furthermore, Russian aggression had given rise to what might be dubbed—after the equally mythologized spirit of August a century prior —a Ukrainian “Spirit of 2014.” Ultimately, Russian mechanized units had to save their separatist allies from being decimated at the hands of Ukrainian volunteers and armed forces, newly burning with patriotic fervor after the events of that spring. I have studied this spirit of resistance through the so-called volunteer battalions: militia units that largely self-mobilized to defend Ukrainian territorial integrity immediately after the Maidan revolution.

During the next eight years, Ukraine reformed its political system and military while simultaneously engaging in nation-building. Following Putin’s war against Ukraine, Russia was often assigned the role of the alien and hostile “other.” Thousands of Ukrainians have fought against Russian-led separatist forces in Donbas. When describing their enemy, they often use the words “separatist” and “Russian” synonymously.

These developments in Ukrainian culture and politics since 2014 appear to have been missed by Russian decision-makers who decided in 2022 to invade. It should have been obvious that Ukrainians would again resist, now even more strongly. One explanation for the mistake is the limited Russian interest and investments in understanding Ukrainian realities. Another is that the decision to invade Ukraine was made by a small group of people. It feels improbable that the yes-men around the increasingly isolated Putin would question his expressed beliefs about feelings of unity between Russians and Ukrainians. The report of the arrest of the FSB foreign intelligence branch leadership behind the Ukrainian survey research suggests that the intelligence failure contributed to the flawed original Russian strategy.

And so the revised strategy includes the awful and largely frustrated, yet offensively logical, broadening of attacks to include civilian targets. It is these daily attacks against Ukrainian civilians that our Ukrainian friends bring up in our online discussions. Ultimately, the outcome of the war will demonstrate the efficacy of Putin’s use of violent force to change Ukrainian culture and history and to make real the fiction that he and others around him have dreamed about.

Naturally, Ukrainians have a say in this outcome. In contrast to the Russian failure to repeat their 2014 scenario, the Ukrainian “Spirit of 2014” has expanded to a countrywide—even worldwide—“Spirit of 2022.” Virtually all my informants now defending Ukraine envisage that the war is ultimately a war of wills and, in that sense, “Ukraine has already won.” Unlike the invading Russians, Ukrainians are defending their home and cannot retreat.

Ethnography offers one way to gauge not only suffering and its political effects but also strategic cohesion—where people stand in relation to their societies. Though awful, suffering can also generate increased resistance. Indeed, Ukrainian morale appears high after many relatively easy victories against Russian forces, combined with the terrible losses incurred during the war’s first three weeks. However, it is less frequently less spoken of that Russia can afford many more mistakes than Ukraine because of its material superiority.

Even from a distance, the war readily becomes a personal affair for ethnographers who are following it. Every Ukrainian whose online presence goes quiet signals a friend killed owing to disagreements over the past, present, and future of Ukraine, its people, and its culture.