Detention, In Frame

From the Series: Abolitionist Pedagogies

From the Series: Abolitionist Pedagogies

For a piece on abolition, it might seem counterintuitive to start with a “frame.” A frame typically binds our view of something, rigidly limiting our attention to what lies within the frame’s borders, rather than outside of it. In that way, it encloses our vision rather than allows for its expansion. This, in many ways, runs counter to the aims of abolitionist thinking, which encourages movement, reconfiguration, or a “vigilant imagination.” Yet what I’m advocating in this piece is for instructors to consider incorporating a specific kind of non-figurative frame in their reading assignments, that found in comics, “co-mix” (Spiegelman 2012), or the graphic or sequential art text. [1]

A unique and dynamic storytelling medium, graphic texts combine a series or sequence of illustrations, separated by frames or panels, with some form of limited descriptive, explanatory text. The format is wide-ranging in its possibilities for form, aesthetic approaches, genre, length, and narrative style. Taken seriously as instructive material, graphic texts expand opportunities for how and what we use to teach students, particularly about less visually accessible subject matter. Additionally, they support our students to potentially connect more meaningfully and affectively with stories about the ways that people are impacted by, and resist, oppressive punitive structures. Paired with traditional written texts, graphic texts both practice and pave a (future) way for abolitionist thinking in our classes.

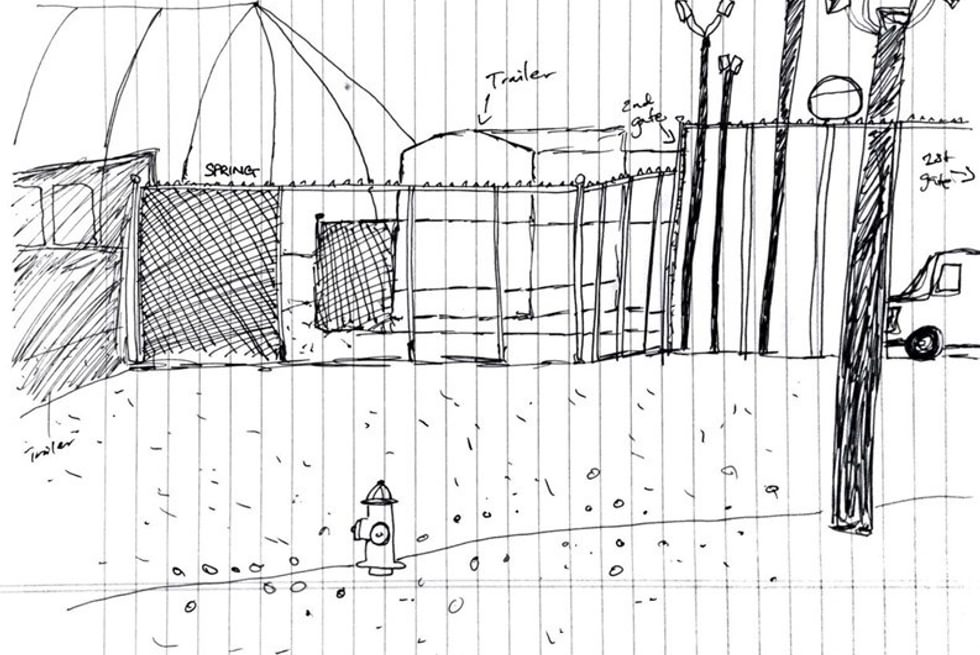

For example, in the case of the U.S., migrant detention centers are renowned for their lack of visibility. Scholars often characterize them as “invisible” (e.g. Dow 2004; Danze et al 2021; Minian 2024) and sometimes as “shadow prisons,” both for the ways in which they are frequently located in places far from public view or scrutiny and also how they commonly operate under murky, secretive legal conditions (Just Future Project, 2018). As such, detention centers are in particular need of more extensive, accurate visual representation. During my doctoral fieldwork in migrant family detention centers in Texas, I struggled with how to do this, given the severe restrictions placed on the use of visual documentary tools inside these spaces. Recognizing the dearth of representation there, I explored alternative visual techniques. One of the ways I approach this problem now, in teaching about detention or incarceration more generally, is through deploying the “invisible art” (McCloud 1993) that is the comic or graphic text in my assigned reading materials in various classes.

Though there are many excellent graphic texts that an instructor could choose to use for their classes that feature detention as a subject, I’ll just focus this discussion on a handful that I’ve used for my own classes. Alongside those below, I’ve offered potential traditional books or articles to consider pairing for lessons (though these could really be paired with many others not noted here) and with one audio-based pair recommendation. I’ll list other graphic texts that I would recommend using at the end of this piece, as well. As a note, each of the four referenced below are non-fiction or memoir-based texts, though I have also used historical fiction and fiction graphic texts, as well as those that blend memoir and fiction. Additionally, while none of these texts are explicitly ethnographic in nature, the “ethno-graphic” text, as Didier Fassin (2022) names it, offers an important collaboration between ethnographic research and the sequential art format of storytelling. I do also use these truly engaging texts or short-form pieces, whenever possible, when teaching on other subjects and would encourage others to explore them as well (like those found in the University of Toronto Press’s ethnoGRAPHIC series, for instance, or in the dynamic work of artist-scholars like Letizia Bonanno or José Sherwood González).

Dominic Davies (2020) draws our attention to the ways that the graphic narrative “strives to counter the invisibilising conditions of…exceptional spaces,” like detention centers along the U.S.-Mexico border, and that such work serves as a kind of “spatial antidote to the violent logics of the world’s current dispensation of bordered nation-states” (15). Each of the pieces presented below, I would argue, contribute to this work in importantly different ways, using a wide variety of stylistic approaches.

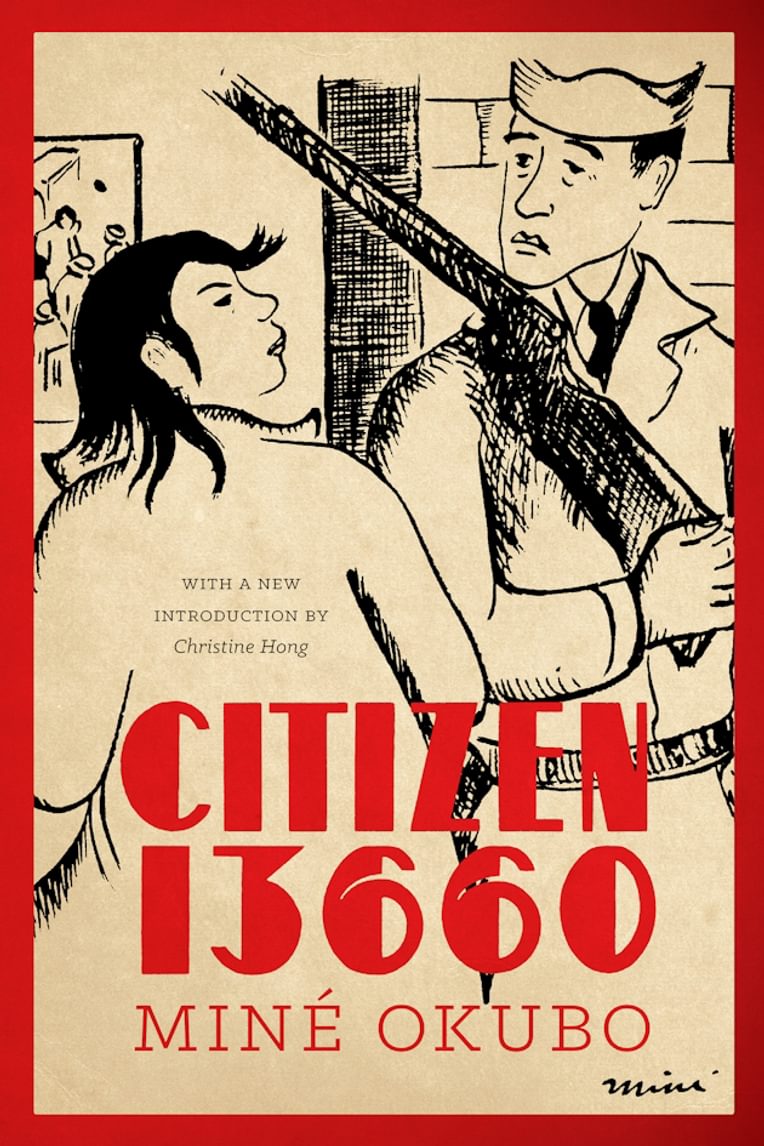

One of the first graphic texts I assigned in a class on the historical progression of migrant incarceration in the United States was the graphic memoir, Citizen 13660, by Japanese American author and artist Miné Okubo. Citizen, which is a graphic documentation of Okubo’s experiences in the euphemistic “relocation centers” in which Japanese Americans were incarcerated during the second World War, is both an example of an early graphic text, as well as an important ethnographic-style historical record from within these spaces. Her style, pairing a single, framed drawing on a page with a small amount of descriptive accompanying text, is unique for today’s format, inviting greater, slower attention to the scenes which she depicts. Those scenes primarily display everyday life in the camps, hence the natural connection to ethnographic study, and this is further supported by the written text. Yet the reader also gets to feel the sorts of pains, degradation, and even pleasures incarcerees experienced through her artistic choices. Her material presence in each of those images, as a kind of recurrent “character,” also allows readers to connect with the story in a different way, observing alongside the observer who is herself imprisoned. Additionally, her work opens opportunities for discussion on the ways in which visual representations can be co-opted or sanctioned by carceral authorities, as her work was with War Relocation Authority (WRA) officials.

Lee, Erika. 2019. America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States. New York: Basic Books.

Varner, Natasha. 2021. “Social Science as a Tool for Surveillance in World War II Japanese American Concentration Camps.” University of Arizona Press, Open Arizona.

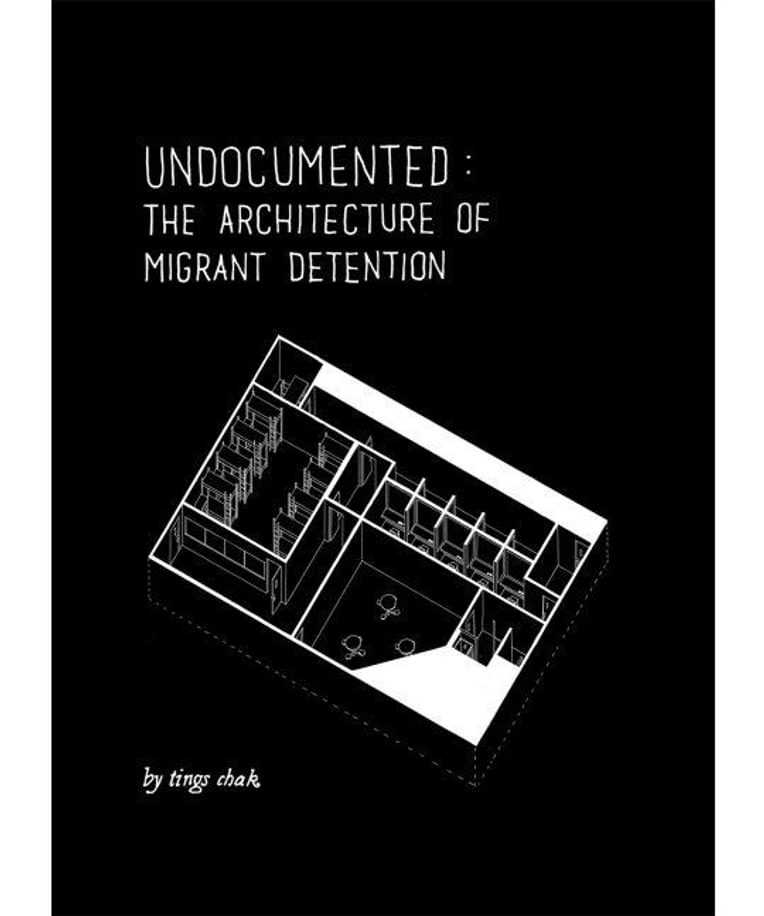

Activist and artist Tings Chak’s Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention (2014) tells a story, or “illustrated documentary” of Canadian immigrant detention facilities, through the lens of space and architectural structures (from the perspective of Chak, who is trained in architecture). Undocumented is a relatively short yet impactful piece, due, in part, to the use of stark scenes that draw out senses of both solitude and intimacy in these spaces, along with detailed spatial specifications to help illustrate the constraints built into the design of this environment. The text also speaks very clearly to the complexity, and intentionality, in how detention centers exist simultaneously within and out of view: “spaces of incarceration are both nowhere and everywhere, blended into our landscapes. But their invisibility is no coincidence. We hide the things that we don’t want to see, or that we don’t want seen” (18). Finally, this work also brings into conversation activism and organizing around anti-carceral projects.

Tschumi, Bernard. 1981. “Violence of Architecture.” Reproduced in Artforum.

Martin, Lauren L., and Matthew L. Mitchelson. 2009. “Geographies of Detention and Imprisonment: Interrogating Spatial Practices of Confinement, Discipline, Law, and State Power.” Geography Compass. Vol. 3, no. 1: 459–77.

den Elzen, Ella. 2020. “Between Borders and Bodies: Revealing the Architectures of Immigration Detention.” Journal of Architectural Education, 74, no. 2: 288–98.

Jérôme Tubiana and Alexandre Franc’s Guantánamo Kid: The True Story of Mohammed El-Gharani (English title) is a significant graphic memoir that not only tells the story of the one of the youngest detainees ever to be incarcerated at the Guantánamo Bay detention camp, and one of only a few Black prisoners at the time; it also paints a picture of various post-9/11 “war on terror” responses, including extralegal extradition and interrogation practices and the use of other “black site” spaces of illegal imprisonment. While situated differently amidst conversations about migrant detention—as the way in which the camp functions in this context is not exactly as a migrant detention facility but rather a prison primarily for extradited foreign nationals—the facility, and the historical era it has come to represent, plays an undeniably significant role in how incarceration of migrants shifted and, importantly, dramatically increased. The physical space on which this facility sits, furthermore, is part of a longer history, indeed the history of migrant detention itself in the United States (and the paired reading suggestion from Jenna Loyd and Alison Mountz unpack this). One additional contribution this book offers is its very unique perspective, that of a child, living through indefinite incarceration, and this viewpoint is complimented by the artistic and narrative choices made by the author and illustrator. Reading this alongside other personal accounts, like those of adult detainees (as found in Nasser’s podcast noted below), offers important contrast. I found this to be something that facilitated a stronger connection between my younger students and the topic of this text, especially for those that had very little prior awareness of this facility and its associated practices.

Loyd, Jenna M, and Alison Mountz. 2018. Boats, Borders, and Bases: Race, the Cold War, and the Rise of Migration Detention in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Li, Darryl. 2022. “Captive Passages: Geographies of Blackness in Guantánamo Memoirs.” Transforming Anthropology, 30, no. 1: 20—33.

WNYC’s Radiolab podcast series, The Other Latif, by Latif Nasser.

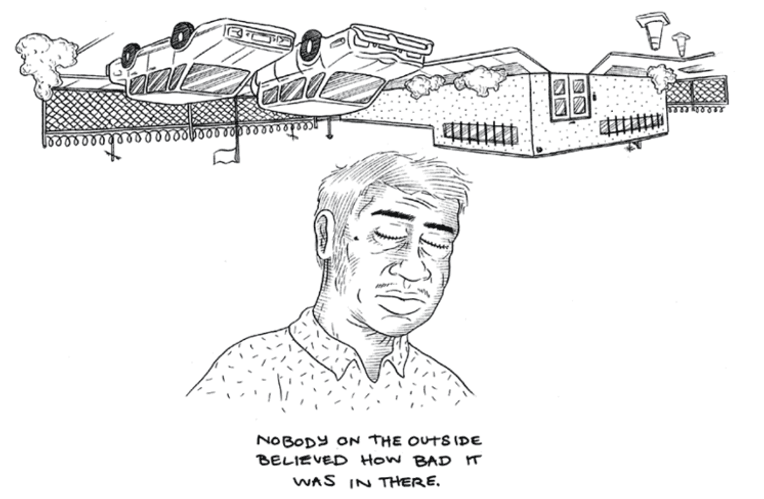

A final “text” I’ve appreciated using in my classes is a webcomic, “At Work Inside Our Detention Centres: A Guard’s Story,” by Nick Olle and Sam Wallman. This graphic piece tells the story of migrant incarceration from another, no less important, perspective: a detention guard. This memoir-style comic explores the experiences of an anonymous former guard employee of the private, multinational corporation, Serco, which operates detention centers across Australia, the setting of the story. This kind of narrative representation is crucial for a holistic understanding of the kinds of differential traumas inflicted upon people who move throughout these spaces, but also how the ever-expanding private entities engaged in migrant carceral “management” operate internally. And yet despite this, currently, too few graphic or even non-graphic stories from this necessary viewpoint of migrant detention exist, so this work fills a critical gap. Speaking back to the aims of ethnographic documentation, this work importantly serves to represent everyday experiences of detention while also sharing necessary testimony from “the exclusion zone” (Nabizadeh 2019), particularly from a non-incarcerated, “outsider” perspective.

Dow, Mark. 2005. American Gulag: Inside U.S. Immigration Prisons. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nabizadeh, Golnar. 2016. “Comics Online: Detention and White Space in ‘A Guard’s Story’.” ariel: a review of international english literature.

Bailey-Hall, Miara L. and Emily P. Estrada. 2022. “Private Immigration Detention without the Immigrants: The Subtle Use of Controlling Images in the Contemporary Era.” American Behavioral Scientist, Vol 66, no. 12: 1645–68.

The inimitable comics theorist and cartoonist Scott McCloud (1993) teaches us that when it comes to understanding the medium, it’s not just about what happens within frames but between them, what he and other cartoonists call “the gutter.” The gutter, the empty space that lies amidst one frame and the next, is where the reader’s imagination and interpretive work enters, where they play their own role in fleshing out the fullness of the story being told. This leads to what is called the act of “closure” in interpreting visual media, meaning “observing the parts but perceiving the whole” (63). Zooming out, McCloud also argues that closure plays a crucial role in our ability to make sense of an “incomplete world,” suggesting that in “in recognizing and relating to other people, we all depend heavily on our learned ability of closure” (63).

Teaching with graphic texts is both about closure but also its opposite: abolishing enclosure. Bringing sequential art or graphic texts into the classroom, especially when we’re teaching about less visualized forms of incarceration or carceral experience, supports the kind of holistic understanding we as anthropologists aim for, while also expanding the possibilities for ways that students can come into closer contact with these spaces and experiences. Detainees and other incarcerated persons are not invisible, but in the classroom, without accurate, engaging, and multiply-representative visual media—the kinds which visual anthropologists and illustrators create every day—they can feel that way. Arguing for the use of graphic texts in classes that center incarceration, generally, as a way to “visualize abolition,” Michael Sutcliffe (2015) notes that “students can approach visual media as a meeting point with their lives rather than as a departure, and look to the ways visual rhetoric complicates conventional readings, especially around particularly affective topics” (2). Teaching for abolition, then, doesn’t just involve learning about oppressive, community-harming carceral structures, but feeling them.

Establishing a greater sense of proximity to these issues and spaces, through pedagogical strategies like these, creates opportunities for imagining alternative worlds (something comics have always been particularly good at). Graphic texts help us and our students feel in sometimes new and profound ways. In the way that feelings have been mobilized to support punitive practices and structures (Lamble 2021), so too can we use these tools in our classes to move abolitionist thinking into frame.

Abe, Frank, et al. 2021. We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration. Seattle, Wash.: Chin Music Press.

Ahmed, Safdar. 2022. Still Alive: Graphic Reportage from Australia’s Immigration Detention System. Seattle, Wash.: Fantagraphics Underground.

Ahrens, Lois, et al. 2008. The Real Cost of Prisons Comix. Oakland, Calif.: PM Press.

Chute, Hillary L. 2017. Why Comics?: From Underground to Everywhere. New York: Harper Perennial.

Fassin, Didier, Frédéric Debomy, and Jake Raynal. 2022. Policing the City: An Ethno-Graphic. New York: Other Press.

McCloud, Scott. 2000. Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form. New York: Harper.

Mirk, Shay Sarah, et al. 2020. Guantanamo Voices: True Accounts from the World’s Most Infamous Prison. New York: Abrams ComicArts.

Ruillier, Jérôme. 2018. The Strange. Montréal, Québec: Drawn & Quarterly.

[1] The terms of this particular textual format have been effectively used interchangeably, with different associated writers and theorists taking different sides on which term more accurately describes the medium. Purely for simplicity’s sake, here, I’ve chosen to group various deviations within the form through the term “graphic text.”

Chak, Tings. 2014. Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention. Ad Astra Comix.

Danze, Alicia, Rebecca Maria Torres, and Caroline Faria. 2021. “Contesting Invisibility of Immigrant Detention Landscapes in Texas.” In The Routledge Handbook of Development and Environment, 128–42. London: Routledge.

Davies, Dominic. 2020. “Dreamlands, Border Zones, and Spaces of Exception: Comics and Graphic Narratives on the US-Mexico Border”. a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 2: 383–403.

Dow, Mark. 2005. American Gulag: Inside U.S. Immigration Prisons. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fassin, Didier, Frédéric Debomy, and Jake Raynal. 2022. Policing the City: An Ethno-Graphic. New York: Other Press.

Just Future Project. 2018. “What is a Shadow Prison?”

Lamble, Sarah. 2021. “Practising Everyday Abolition.” In Abolishing the Police: An Illustrated Introduction, edited by Koshka Duff. Dog Section Press.

McCloud, Scott. 1993. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Perennial.

Minian, Ana Raquel. 2024. In the Shadow of Liberty: The Invisible History of Immigrant Detention in the United States. New York: Viking.

Nabizadeh, Golnar. 2019. Representation and Memory in Graphic Novels. New York: Routledge.

Spiegelman, Art. 2012. Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps. Montréal, Québec: Drawn & Quarterly.

Sutcliffe, Michael. 2015. “Visualizing Abolition: Two Graphic Novels and a Critical Approach to Mass Incarceration for the Composition Classroom.” SANE Journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education. Vol 2, no. 1, article 6.