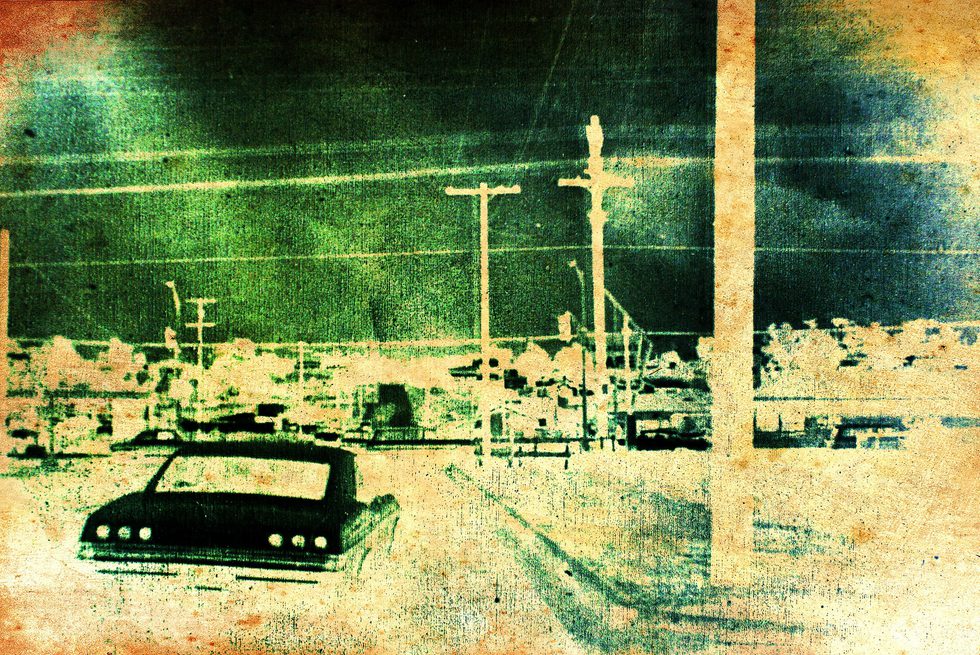

Disaster: Deviation

From the Series: Disaster

From the Series: Disaster

Four months after what was called Japan’s compound disaster (of earthquake, tsunami, and meltdown at the Daiichi and Dainichi nuclear reactors in Fukushima), I went to one of the towns worst hit on the northeastern coast of the country. This was July 2011 and I joined the ranks of cadres of volunteers digging into and out of the mud of what once had been peoples’ existences. We entered the sludge of remains—a gooey mess littered with indecipherable waste oozing a stench so distinctive I can still smell it today. And whether we were there for two days or two weeks, our job was to dig: remove mud from the gutters on the side of the streets and under the schools and temples. And remove whatever of value (mainly photos or certificates) from the rubble of what once had been homes.

What we, as volunteers from all over Japan (and a couple of us, beyond), had gone to this disaster zone to do was not exactly to intervene—if we adopt the conventional definitions of the word meaning to interfere with an outcome (or condition or process) or to come in between parties or things. We, of course, hoped to clean things up and help move what was destruction into a state—and stages—of recovery and reconstruction. But life—and death—was still raw at that moment and the work we performed, while arduous and well-intended, didn’t move mud at a rate anything like the bulldozers and machinery also sent into help. Volunteers went anyway and expended labor, in these tormented conditions of disaster, literally for months.

My point is only this. Ben McMahan’s prompt to us is to consider what precisely a disaster is. And, in responding, Vivian Choi writes that disasters are processual and multiple, occurring (as in the doubling of disaster, at once natural and political that she examines in Sri Lanka) at a spectacular scale that settles, all too soon, into an ordinariness that becomes a constant presence. Quoting Maurice Blanchot, she notes that a disaster is what cannot be written, which poses troubling issues for translation—if translation is indeed (part of) the response for the survivor, relief worker, or anthropologist to disaster. But perhaps there are moments or aspects of disaster that not only don’t but shouldn’t lend themselves to translation. And the same might be true of intervention per se. Which is all to say, there is a space, a time, a fragility in the everydayness of survival—whether emerging from a disaster with a capital “D” or from the ordinariness of just getting by—that eludes both representation and decisive action. Referring to the precarity of life itself, Kathleen Stewart speaks of its dwelling forms—of how precarity is the unworlding of worlds that once or should have held together in comfortable, predictable ways. And, as an anthropologist, she contemplates how to feel our way into this unworlding through a form of writing that is neither representational nor interventionist but in tune with the scratchings, longings, and survival tactics of what Fiona Ross (2010), another anthropologist working on precarity, calls raw life. “Precarity, written as an emergent form, can raise the question of how to approach ordinary tactile composition, everyday worldings that matter in many ways beyond their status as representations or objects of moralizing” (Stewart 2012, 519).

In the immediate aftermath of 3/11 in Japan, there was certainly a need to both translate the impact of the disaster on/of those variously endangered and to intervene in recovery, relief, and also activism (against restarting the nuclear reactors, for example). But there was also a need to simply dwell in the muddiness of all that had been destroyed, lost, and shaken up for so many people. To accompany the lives and deaths of those who had been hit the hardest (Lingis 1994). A dwelling, which is the word Elizabeth Povinelli gives to fieldwork, can also be a form of sociality, an action of sorts, a way of enduring the unendurable. The line between disaster and nondisaster is often very thin and how to do anthropology in such a space is what I have been struggling with in my current work on precarity in Japan.

Lingis, Alphonso. 1994. The Community of Those Who Have Nothing in Common. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ross, Fiona C. 2010. Raw Life, New Hope: Decency, Housing, and Everyday Life in a Post-Apartheid Community. Claremont, South Africa: University of Cape Town Press.

Stewart, Kathleen. 2012. "Precarity’s Forms.” Cultural Anthropology 27, no. 3: 518–25.