Don’t Break the State: Indivisibility and Populist Majority Politics in Nepal

From the Series: Majoritarian Politics in South Asia

From the Series: Majoritarian Politics in South Asia

Images of broken states, broken regions, and broken bodies animated the populist majoritarian politics of high-caste Hindus during the writing of Nepal’s new federal constitution (2008–2015). Linking the territory of the state to the idea of national unity, and expressing that relationship with their bodies, high-caste Hindus opposing the division of Nepal into federal provinces would simply say, “We will not be broken.” As my doctoral fieldwork on Nepal’s state restructuring unfolded, I found myself chasing the affect of Hindu politics circulating in rallies and assemblies in the lowland Tarai region of Farwestern Nepal. A few weeks before the constitution’s promulgation in September 2015, I stood shoulder to shoulder among high-caste Bahun and Chhetri men joyfully celebrating an anticipated victory:

Akhanda Sudurpaschim zindābād!

Hamro Sudurpaschim tukryāuna paidaina!

Long live the indivisible Farwest!

Our Farwest will not be broken!

The mood was high because national politicians had agreed on a provisional six-province federal system for the country’s post-conflict constitution. As a compromise, the map merged the Tarai and Hills of the Farwestern and Midwestern Development Regions into a super-sized “Province Six.” But those gathered around me considered this to be a minor obstacle toward the goal of securing a separate Indivisible Farwestern province. What mattered was that the map rejected the popular model of ethnic federal provinces, including a province for indigenous Tharu in Farwest Tarai. Instead, the map joined the Hills and Tarai, favoring feelings of indivisibility articulated by their movement.

Amid the cheering crowd, the district president of the Rastriya Prajatantra Party—Nepal’s conservative, Hindu, royalist party—stepped forward to frame the moment. “I don’t need to say a lot,” he began. “All you friends know that since a long time our party has said that our state does not need federalism. That federalism was brought by outsiders and for that reason federalism was not abhiṣek [Nep., anointed, as in a religious ceremony] . . . We don’t believe in federalism . . . But today, that twisted federalism has gone ahead and the constitution has been constructed.” Gathering momentum, he declared, “We made our Movement saying that we, on the side of the Indivisible Farwest believe that our state and our Farwest, must not be broken!”

Bahun and Chhetri leaders of the Indivisible Farwest Province movement represented themselves as populist heroes, saving Nepal from fragmentation by ethnic provinces. Their movement provided a scaffold for wider Hindu solidarity in the federal restructuring process. A dominant minority in national politics, Bahuns and Chhetris constitute the demographic majority in the Farwest. However, despite high symbolic capital, they regarded themselves as forgotten by their caste cousins in distant Kathmandu. When mid-twentieth century malaria eradication campaigns made the Tarai conducive for year-round settlement by people from the Hills, Bahuns and Chhetris left the poverty of the Hills to live side by side with the region’s indigenous inhabitants, the Tharu. Experiences of subsequent bonded labor, marginalization, and land dispossession boosted Tharu demands for their own province (Tharuhat/Tharuwan) in the New Nepal.

The Indivisible Farwest movement opposed the Tharu province violently, resulting in loss of life and mass arrests among the Tharu community.1 By putting their bodies in front of political change, supporters of Indivisible Farwest prevented the formation of an ethnic province and consolidated a public intent on preserving Nepal’s past territorial and ideological form. Nepal’s federal structure today features seven provinces, including the Farwestern Province, the majority of which connect the Hills and lowlands. On a map, the “New Nepal” looks remarkably like the “old.”

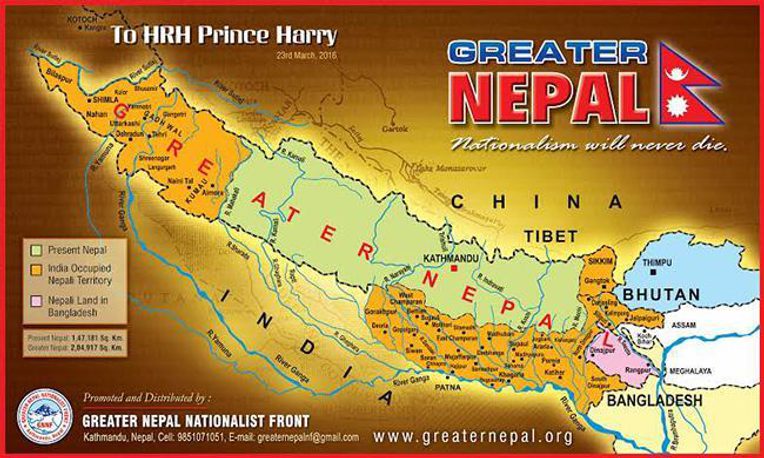

It is unsurprising, then, to note how the framing of akhanda—the indivisible—informing Bahun-Chhetri populism in Nepal echoes ideas of the “Greater” state prominent in South Asia. Akhanda Nepal and Akhand Bharat—Greater Nepal and Greater India—each stretch the boundaries of nation-states through irredentist dreams of empire, extending an imagined national community across histories and landscapes of fleeting, tangential connection. Based on military conquests of the Gorkha Shah Dynasty, Akhanda Nepal exceeds the state’s present boundaries at the Mechi and Mahakali Rivers to encompass Darjeeling, Kumaon, and Garwhal and parts of Bangladesh.2 Akhand Bharat, glorifying the precolonial network of Hindu princely states and transnational influence of Hinduism, envisions Indian authority across South, Southeast, and Central Asia. In each scenario, akhanda calls attention to the wholeness of the past and the fragmentation of the present. The demand for indivisible provinces in Nepal replicated this vision of whole pasts and fragmented futures, but at the expense of preserving a state form that denies inclusion, opportunity, and dignity to the non-high-caste Hindu majority.

Standing inside the politics of populist majoritarianism, looking around at the faces of high-caste men united in their zeal for an indivisible region in an indivisible Nepal, I see how akhanda connects semantically and affectively to its opposite, khaṇḍita: the experience of being cut, torn, broken into pieces. Dividing Nepal into federal provinces was painful for those who clung to the idea of akhanda. It was held at bay at all costs. It created a “New Nepal” that affirmed the “old.”

1. Shortly after this Akhanda rally, eight security personnel were killed and a toddler died by a stray bullet when violence erupted at a pro-Tharu province assembly near Tikapur. Vigilantes responded swiftly, destroying Tharu homes and properties as security forces detained and arrested suspected Tharuhat supporters. For more information about the Tikapur incident, please read Abha Lal’s 2019 article for the Record, “After Years of Media Trail, A Stunning Verdict in the Tikapur Case.”

2. The Greater Nepal Nationalist Campaign handed over a map of pre-1816 Greater Nepal to Prince Harry in a bid to convince the British government to return territory now in India to Nepal. In 2019, the same organization launched a signature campaign for the return of territory “lost” in the signing of the Sugauli Treaty.