Firescapes, Smoke, and Woe

From the Series: Firestorm: Critical Approaches to Forest Death and Life

From the Series: Firestorm: Critical Approaches to Forest Death and Life

Orange flames. Yellow-brown smoke. Over the past two decades, fires have engulfed both Southeast Asia and the West Coast of the United States like never before. These are firescapes, landscape-scale fires of unusual intensity and scale. Fire is elemental, but firescapes are societies’ destructive creations, remaking lifeworlds through the terrible synergies of industrial capitalism and a changing climate that is heating up and drying out both Southeast Asia and the West Coast.

In Indonesia, such fires burn in places like Jambi Province, Sumatra, with its plantation monocultures of oil palm and timber spreading across hills of tropical rain forest. Along the United States’ West Coast the fires engulf places like Mendocino County, with its plantations of grapes, marijuana, and pine carved out of the mountain oak and redwood.

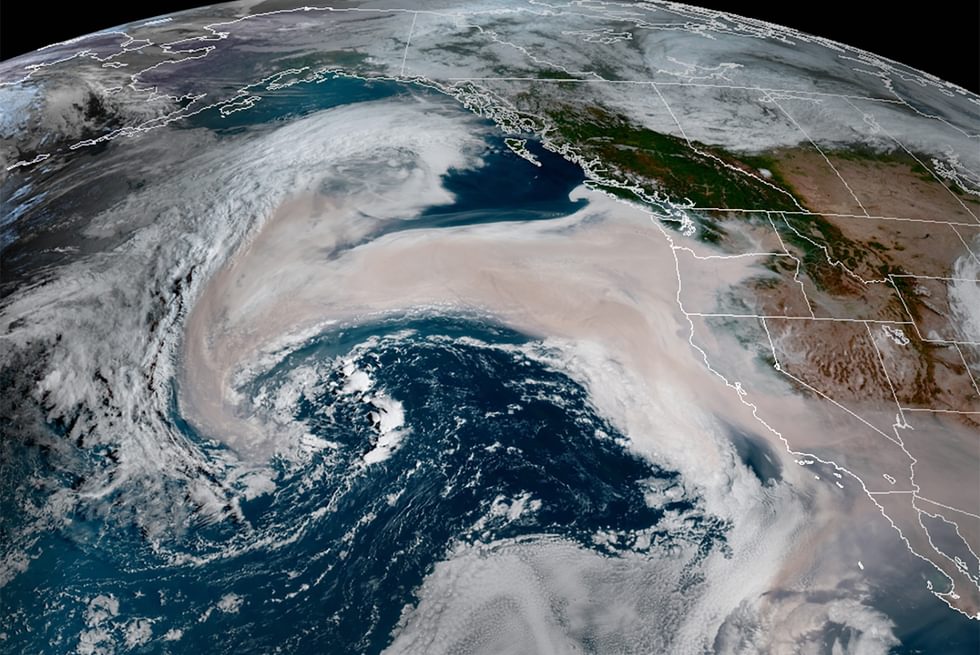

Extending beyond the heat of the flames are the even larger swaths of smoke that rise and flow over the Pacific Ocean from both the east and west, filling the atmosphere with toxins—gasses, heavy metals, and particulates. People, animals, and plants on both sides of the Pacific Rim breathe, drink, and absorb these toxins through their pores—taking up the burned forests and human-built materials of the firescape into their bodies.

The first time I awoke to smoke that blocked out the sun was in the fall of 2015, when I was working in a rural town in upland West Sumatra. The skies stayed dark for months. The 2015–2016 fires that engulfed Sumatra and Borneo went on to become one of the most harmful environmental disasters in recorded history. A century of industrial oil palm plantations and logging estates killed the forests and destroyed waterways. Then a cruel synergy of El Niño drought, deforestation, soil desiccation, and commodity tree crops’ high flammability established the conditions for human fires, both intentional and accidental, to become landscape-scale fires that killed millions of rain forest lifeforms, caused as many as an estimated one hundred thousand premature human deaths, and for a few months emitted more carbon into the atmosphere than the whole of the U.S. economy.

Tens of millions of Indonesians breathed the smoke in their homes, fields, and offices. Coughing, wheezing, and scratchy eyed, my Minangkabau neighbors told me they thought the town’s death gong sounded more often than usual. There were too many heart attacks and strokes, they said.

The second time I awoke to smoke obscuring the sun was five years later in 2020, in the California Bay Area where I live with my partner and young children. At eleven in the afternoon there was nothing more than a soft orange glow in the sky. Labeling it, “the day the sun didn’t rise,” the San Francisco Chronicle declared people in the Bay Area had “apocalypse on their mind.” It was the fourth straight year of catastrophic fires across the West Coast forests. Indeed, the ten most destructive burning seasons on the West Coast have all come since 2003. Human-caused climate change has brought the droughts and heat that exacerbate the fires, but a century of settler colonial mismanagement of the forested landscape established the ecological conditions that make the forests so vulnerable now.

Living in these firescapes, as an ethnographer in Sumatra and then in the Bay Area with my own family, ruptured the boundaries of my fieldsite and my homelife. I was struck by the resonance of the trajectories of change the last century brought to both places, feeling that the origins of the fires in both locales had much to do with the closing decades of the nineteenth century, when both Sumatra and California were theaters of colonial cruelty and violence as white settlers and colonists destroyed existing Indigenous lives and lifeways to begin the first large-scale capitalist exploitation of the forests.

Among the incommunicable losses of the Dutch’s colonization of the Indonesian archipelago, the American Indian genocide, and the subsequent rise of industrial capitalism in both Sumatra and California is the loss of many of the careful ways Indigenous Sumatrans and Californians use fire to aid their efforts of cultivation and harvests of plants and game, and reduce the chance of more threatening landscape-scale fires.

In place of these relations of care between people and fire, for many in Indonesia fire has become closely associated with the industrial plantations and the dispossession they bring. A few years ago, I joined an agriculturalist and environmental activist from upland Borneo to watch as an agribusiness burned the forests behind his home to make way for a new oil palm plantation. On a hill overlooking the firestorm the man exclaimed,

Do you see all the smoke? It has become like this, the land will be covered in oil palms. The forest has been cut down . . . We are suffering. We can see it now, the smoke. That is what has brought so much woe to the people . . . We don't ask for that. We cannot live like that, if the forests are gone and the rivers eroded away.

A similar foreboding feeling about the future can be found in the Bay Area, a woe that is also born from all the smoke. But instead of being focused on the expansion of new industrial plantations, the fulcrum of the problem is more often spoken about in terms of climate change and the need to decarbonize the global economy. Part of the reason for this is that the fires of the West Coast are more closely determined by the accelerating climate shifts of a warming atmosphere than Indonesia’s fires are, which appear to be more connected to forest fragmentation and the decadal swings of El Niño. But Indonesia’s fires emit far more carbon than California’s, beyond even the massive forest fire emissions of the Amazon. For a friend I grew up with in the Bay Area, the most terrifying thing about the 2020 firescape was her rising sense that this was only the beginning of the firestorms to come over the next few decades under the current global carbon emissions regime.

With another year of new firescapes from Indonesia to California unfolding, one certainty is that they mark the danger and suffering of humans’ dominant relations with the land, forests, and many more earth beings, joining disparate lifeworlds in tragedy.