Forest Urbanism: Urban Forest Life and Rural Forest Death in the Brazilian Amazon

From the Series: Firestorm: Critical Approaches to Forest Death and Life

From the Series: Firestorm: Critical Approaches to Forest Death and Life

The first time I visited the Amazonian state of Acre, Brazil, in 2012, I landed at the airport in the capital city of Rio Branco at night. Walking the tarmac in a sleepy daze, I strained to see the famed Amazon rain forest I had come to study. It appeared in outline: quiet darkness against the small airport’s dull illumination. I also strained to see it in the days that followed as I wondered Rio Branco’s dusty streets. Was I really in the Amazon, I wondered? Where was the rain forest of my imagination?

When we outsiders imagine the Amazon, we tend to think of a “pristine” (read: nonhuman) rain forest or a landscape aflame. We don’t tend to think of cities. But this is where most people in the Brazilian Amazon live—in cities like Rio Branco. The Amazon, as the Brazilian geographer Bertha K. Becker (2005, 73) put it, is an “urban forest.” The forest can be present in cities too. But its presence there is different than that of the living—and dying—forest in rural areas.

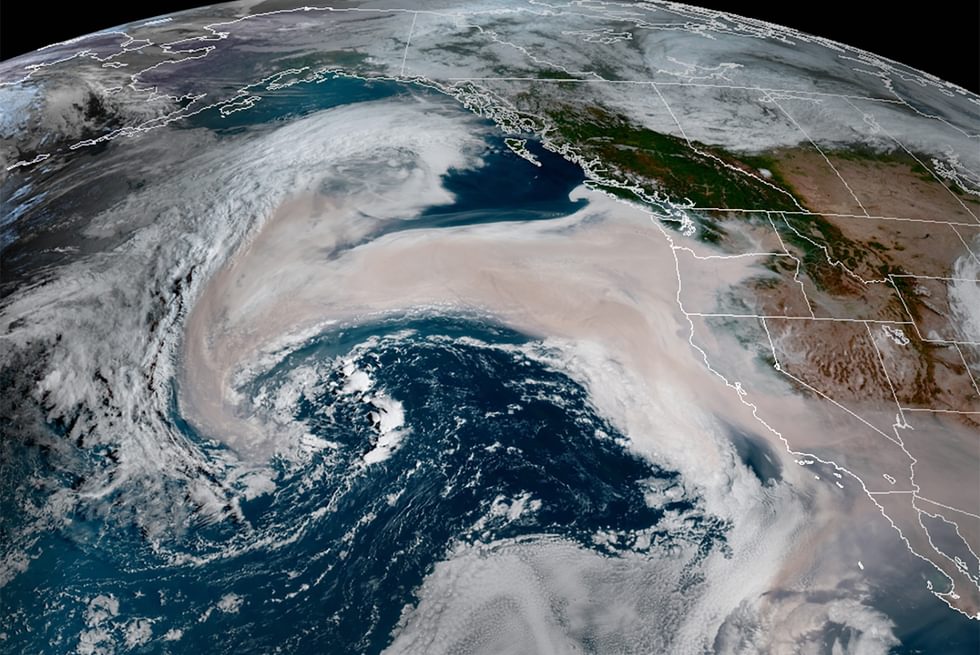

And in many parts of the Brazilian Amazon the forest is dying, or rather is being killed through human-set fires and climate change. The recent increase in deforestation—as well as connected violence against Indigenous and other forest communities—makes it easy to forget the almost-as-recent successes in reducing deforestation, creating protected areas, demarcating Indigenous lands, and expanding rights to other marginalized communities. These were the victories of socioenvironmental movements and, in some places, supportive organizations and governments.

Such was the case in Acre, where a famed socioenvironmental movement centered on rubber tappers in the 1980s paved the way for the 1998 election of the self-titled “Government of the Forest.” Under its administration, the forest was imbued with meaning as state-sponsored heritage. This urban cultural valorization was part of the state’s larger focus on forest-protective development. The strategy was based on the belief that rural forest protection entailed, in part, transforming the forest’s urban meaning. But the city, particularly Rio Branco, benefited too: support for the forest brought improvements in urban life through garnering outside funding, expanding city-based forest governance, and implementing forest-themed urban revitalization, which is my focus here.

By all accounts that revitalization was needed. Rio Branco had been strewn with trash and without working traffic lights, reliable health services, fresh food, or usable public spaces—a real “piece of shit,” as an activist put it to me.

A kind of forest urbanism unified the government’s project of revitalization. In downtown Rio Branco, government-issued Amazonian architecture—dark wood exteriors topped by ornamental thatched roofs—dotted a new city park. Among the buildings was the Forest People’s House celebrating the state’s Indigenous communities, rubber tappers, and others in statues, photos, and text displays. The Forest Library was located along the park too, where its exhibits recounted the history of the rubber tapper movement, its assassinated leader Chico Mendes, and Indigenous Acreans. The Rubber Museum was close by and the Forest People’s Plaza was a short walk away. Across the street the state legislature met in a big room lined with large wooden carvings depicting the state’s forest-centered history.

Across the river was the Gameleira—the oldest part of the city where rubber used to be collected, now restored as urban leisure space. It was named for the girthy old gameleira tree that shaded the pleasantly restored river walkway. A government website described the tree as a “symbol of the perseverance and resistance that characterize the people of Acre.”

The forest was sometimes presented as part of the present or even the future, as in the Forest Arena and the Digital Forest public wifi network, whose 2009 creation made Rio Branco the first Brazilian capital to provide free wireless Internet. But for the most part, the forest depicted in these revitalized and newly constructed urban spaces recalled the past—the forest when rubber extraction dominated the economy in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; the forest at the center of the rubber tapper social movement of the 1980s. It was a history shared by many of Rio Branco’s residents—descendants of rubber tappers who moved to the city as the price of rubber collapsed. Urban conjurings of the forest as heritage improved urban life and gave it meaning.

This forest was not a landscape of plants, animals, and rural human life. Rather it was often a story of the past told even as the rural forest was destroyed and celebrated forest lifeways were threatened or in decline. Urban residents could enjoy the historical meaning of the forest without the current forest’s discomforts, isolation, poverty, and socioenvironmental destruction.

In their edited volume, Elaine Gan et al. (2017, G1–G2) describe “vestiges and signs of past ways of life still charged in the present” as “ghosts” that “haunt” landscapes. What about when threatened but ongoing ways of life are actively conjured as if they are past? What kinds of ghosts are these? With about 86 percent of the state considered to be forest, Acre’s rain forest is still standing. Indigenous people, rubber tappers, and other forest people celebrated in the city also continue to live.

It’s important to note that many of them benefited from governmental policies during the two decades (1999–2018) of the Government of the Forest and its successors. Moreover, deforestation declined and remained relatively low during much of that time. Yet for many in rural and urban Acre, continued rural poverty and urban-rural inequity made urban celebrations of the forest feel vacuous, connected to charges of corruption. Forest-clearing fires increased dramatically in the final years of the last decade, as they did throughout the Brazilian Amazon. And a large majority of Acreans voted for pro-deforestation far-right presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro and an agribusiness-linked governor in 2018. In this, they voted against both the rural forest and the urban one.

How can urban-dominated societies culturally value forests in ways that support rural forest life and lifeways? This is a question not just for the Brazilian Amazon but for all of us who live in cities and yet depend on the forest in so many ways.

Becker, Bertha K. 2005. “Geopolítica da Amazônia.” Estudos Avançados 19, no. 53: 71–86.

Gan, Elaine, Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, and Nils Bubandt. 2017. “Introduction: Haunted Landscapes of the Anthropocene.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Anne Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, 1–15. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.