Gentrification as Coastal Planning in the Mermaid City

From the Series: Coastal Futures

From the Series: Coastal Futures

Viewing the future in light of the past frames contemporary coastal planning in American cities as part of the schemes and scams of market colonialism of previous eras. These schemes and scams take many forms—settlement, development, redevelopment—working together with bloc-busting social differentiators (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, labor, etc.) to draw capital through spaces to serve the interests of the ruling class. Climate adaptation, then, is simply the next wave of justified displacement, spaces changing hands, and the de- and re-accumulation of capital. In the quest to understand how racial stratification, as one type of social differentiator, affects climate responses in terms of implementing engineering interventions (cf. Vaughn 2022), we are called to examine how histories of race and other differentiators have designed landscapes to date. The future of American coasts may closely resemble their pasts, driven as much by the forces of capital as by the forces of wind and water.

Social stratification is undeniably resilient. There are plenty of illustrative coastal cities, and any one will do. A particularly interesting case is Norfolk, Virginia.

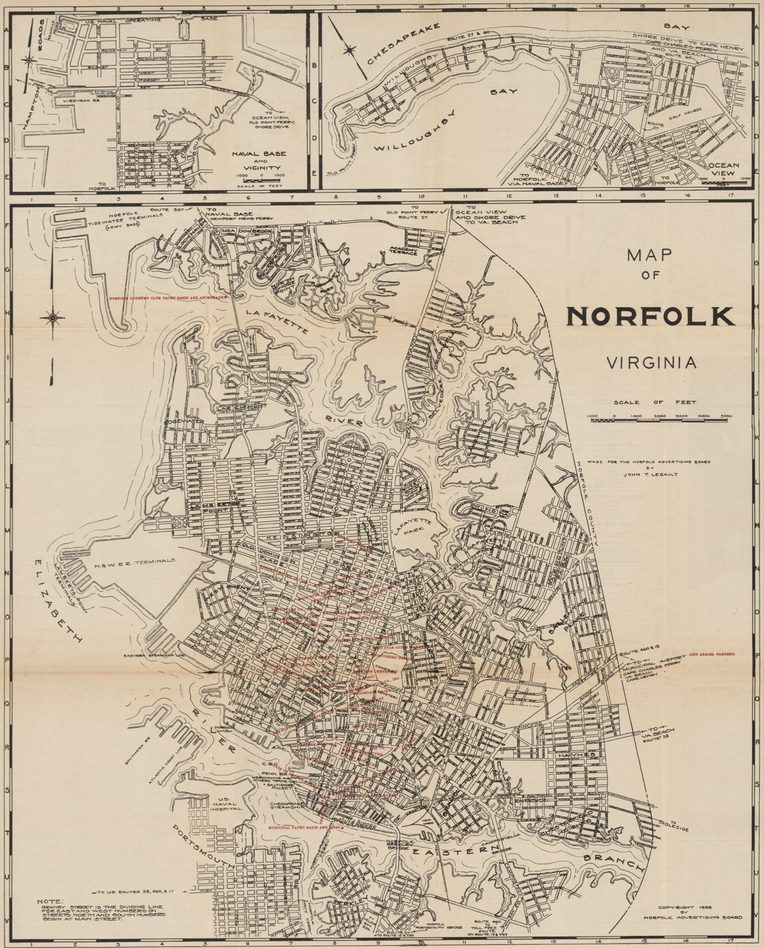

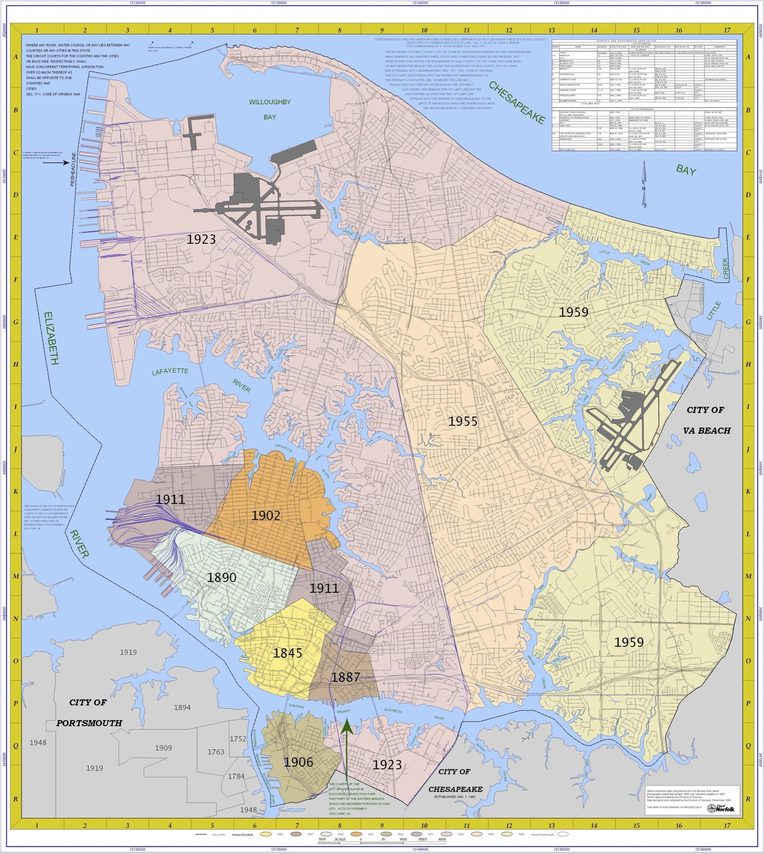

An “historic southern port” (Wertenbaker 1931), Norfolk sits at the crossroads of north and south, on the mid-Atlantic at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Bordered on all sides by water, the city is crisscrossed by inlets and creeks at a uniformly low elevation.

The city is home to 233,000 people and a massive military installation housing the U.S. Atlantic naval fleet and North America’s NATO headquarters. White and Black residents have alternated as majorities in the city throughout the twentieth century, leading to an endless struggle over the distribution of power and space, consolidated over the years in structural racism leading to an endless struggle over the conditions of structural racism and the distribution of power and space. The result has been segregated housing, periods of disenfranchisement for segments of the population, lopsided (re)development, and disproportionate burdens of highways, coal transport and air pollution, flooding waterways, food deserts, and dump sites. This story is familiar in other coastal American metropolises except for Norfolk’s military concentration, one of the heaviest investments of military infrastructure on earth.

Since the Civil War, Norfolk has been a locus of Black life in Virginia and the South (Bonekemper 1970, Lewis 1991, Hucles 1992). For decades, the Norfolk Journal & Guide boasted the widest circulation of any Black newspaper in the United States. Its longtime editor, P.B. Young, embraced Booker T. Washington’s less-than-radical model for integrating Black workers into the socioeconomic structures of the time. For example, when Black tenants in Norfolk organized to withhold rent and end evictions in the early 1930s, Young and his newspaper openly opposed the movement (Suggs 1983). Instead, Young espoused the motto and metaphor, “Build up, don’t tear down,” in a city with finite labor and space.

Before equal housing regulations, the government, real estate industry, and banking system were complicit in stratifying residential landscapes. Government-sponsored Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps from the 1930s openly established sociocultural criteria to grade neighborhoods by their residents, forecasting the trends of investments that would lose or accumulate value, from “best” (A) to “hazardous” (D) (Nelson et al. 2023).

“Slums” in Norfolk were characterized by their residents as well as by the disease, crime, and inadequate infrastructure that their status explained. As one of Virginia’s most populous and diverse cities, Norfolk became a model for city control and planning. A mid-1930s study commissioned by the city manager, for example, justified a 1938 General Assembly law authorizing local housing authorities across the Commonwealth (in a Dillon Rule state) to implement “slum clearance” programs.[1]

The Norfolk Housing Authority (NHA), eventually renamed the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority (NRHA), was created in 1940 to clear out, repopulate, and otherwise sanitize the slums. In the 40s, this meant building wartime defense housing. After the war, in 1949, Norfolk was the first city in the country to receive a housing grant under the Federal Housing Act.

The story repeats: Brambleton corridor, downtown, Portsmouth Bridge Tunnel, East Ghent. Poor and, most often, Black families were displaced with each project, while capital’s priorities reshuffled to move money and forestall integration. In the 50s and 60s, housing and school integration efforts were sometimes met with violence. Streets where Black families bought houses were blocked up with protesting “caravan” traffic; neighbors posted harassing signs and made threatening phone calls; houses were sabotaged and fire-bombed. Despite pressure from Black leadership, including the Journal & Guide, law enforcement refused to intervene.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers staffs a district office in Norfolk. They consider the city to be high risk for loss as the climate changes (U.S. ACOE 2015). The Corps has documented a higher rate of relative sea-level rise for Norfolk than the rest of the Chesapeake Bay from 1955 to 2017, due to contributing effects of land subsidence. The engineers expect that rate to accelerate, predicting the water to rise 0.74 to 2.87 feet in the next century. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicts even higher levels, between 1.51 and 9.95 feet in the same period (U.S. ACOE 2018).

Slow, piecemeal federal engineering projects, such as those proposed by the Corps in Norfolk, are just as likely to exacerbate disproportionate loss—for both poor and Black residents—as they are to mitigate the negative effects of increasing water levels. These plans, themselves economic indicators that affect market trends, are critiqued by local activists and residents, questioning who and what deserves protection (Morrison 2023a, 2023b).

Changing flood forecasts do not change the age-old power of capital. Out-of-town speculators participating in wider real estate markets outstrip the power of locals to protest or even know about properties on their streets or in their neighborhoods. Residents almost always organize too little and too late. Last spring, residents of a downtown neighborhood showed up at a Planning Commission meeting to protest the potential rezoning of a longstanding church into luxury apartments. Emotions ran high at the normally placid, weekday meeting, but the outrage of the residents was too late. The church had been struggling to use the property for years and the parcel sale had occurred months before the relatively pro forma zoning request being considered. Nothing they said could have made a difference.

Norfolk’s climate adaptations are a product of the city’s stratified past and the ways struggle has always shaped the landscape. Within this milieu, capital will continue making the decisions, raising the simple, empirical question of how “gentrification” will proceed as “climate gentrification.” To observe this process, anthropologists and social scientists must trace discursive and pragmatic concepts (e.g., adaptation, resilience, mitigation, management, retreat, planning, etc.). We can expect to find “legal chicanery” (Kahrl 2014) behind supposedly blind indicators of value such as tax assessments (Kahrl 2019), house values and insurance appraisals (McCarthy 2020), city “takings” for projects (Whitehurst 2013), and the cost-benefit analyses justifying engineering interventions (Lin 2013). By exposing these stratified and stratifying processes, we make visible what they mean for reified and nationally-generalized real estate markets and trends. Most importantly, we can reveal justifications for active displacement of specific populations and the ongoing theft and thwarting of intergenerational wealth transmission.

[1] The Dillon Rule is the legal concept of a state’s preeminent authority over all local governmental units such as counties or cities within that state. In Dillon Rule states, local governments are only allowed to pass laws that are explicitly granted by the state legislature. The importance of the 1938 General Assembly law to start “slum clearance” is that what was happening in Norfolk at the time suddenly became the explicit basis for application in all other localities across the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Special thanks to Landon Yarrington, Kim Sudderth, and Alannah Bell.

Bonekemper, Edward. 1970. “Negro Ownership of Real Property in Hampton and Elizabeth City County, Virginia, 1860-1870.” The Journal of Negro History 55, no. 2: 165–81.

Hucles, Michael. 1992. “Many Voices, Similar Concerns: Traditional Methods of African-American Political Activity in Norfolk, Virginia, 1865-1875.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 100, no. 4: 543–66.

Kahrl, Andrew. 2014. “The Sunbelt’s Sandy Foundation: Coastal Development and the Making of the Modern South.” Southern Cultures 20, no. 3: 24–42.

Kahrl, Andrew. 2019. “The Short End of Both Sticks: Property Assessments and Black Taxpayer Disadvantage in Urban America.” In Shaped by the State: Toward a New Political History of the Twentieth Century, edited by B. Cebul, L. Geismer, and M.B. Williams, 189–217. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lewis, Earl. 1991. In Their Own Interests: Race, Class, and Power in Twentieth-Century Norfolk, Virginia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lin, Albert. 2013. “Does Geoengineering Present a Moral Hazard?” Ecology Law Quarterly 40, no. 3: 673–712.

McCarthy, Kristin 2020. “Residential Real Estate Appraisal and Flood Resilience Measures.” Sea Grant Law and Policy Journal 10, no. 2: 115–25.

Morrison, Jim. 2023. “As Norfolk Weighs Storm Protection Plan, Black Residents Want More Say.” The Washington Post. March 15.

Morrison, Jim. 2023. “Norfolk Approves $2.6 billion Storm Protection Plan for City.” The Washington Post. April 26.

Nelson, Robert, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al. “Mapping Inequality: Norfolk, VA.” American Panorama, ed. R. Nelson and E.L. Ayers, accessed June 9, 2023.

Suggs, H. Lewis. 1983. “Black Strategy and Ideology in the Segregation Era: P.B. Young and the Norfolk Journal and Guide, 1910-1954.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 91, no. 2: 161–90.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 2015. “North Atlantic Coast Comprehensive Study: Resilient Adaptation to Increasing Risk.”

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 2018. “Final Integrated City of Norfolk Coastal Storm Risk Management Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement.”

Vaughn, Sarah. 2022. Engineering Vulnerability: In Pursuit of Climate Adaptation. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Wertenbaker, T.J. 1931. Norfolk: Historic Southern Port. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Whitehurst, Emily. 2013. “Norfolk’s Flooding Adaptation Measures: Taking Lawful Precautions or ‘takings’ Lawsuits?” White Paper No. 7. Williamsburg: Virginia Coastal Policy Clinic, William and Mary Law School.