Hands Holding Life

From the Series: HandsOn: Touching the Digital Planet

From the Series: HandsOn: Touching the Digital Planet

I send a greetings message via WhatsApp to my friend, the artist Innocent Nkurunziza, a leading figure in Rwanda’s contemporary fine arts scene.[1] “Greetings, Brother-Friend. How are you doing on this April 20th morning?” It is 3:00 am in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, where Nkurunziza is based, and 9:00 p.m. in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where I teach. Nkurunziza’s predilection for crafting, creating, and conversing in the depths of the night when most Rwandans are fast asleep, makes 3:00 a.m. an opportune time for us to connect with each other. A few minutes pass before my phone flashes with a response from Nkurunziza. “Hello to you, Sister-Friend Aalyia. I am good; just chatting with the universe. What are you thinking about these days?” In typical millennial style, I respond not in words, but with an emoji, of hands.

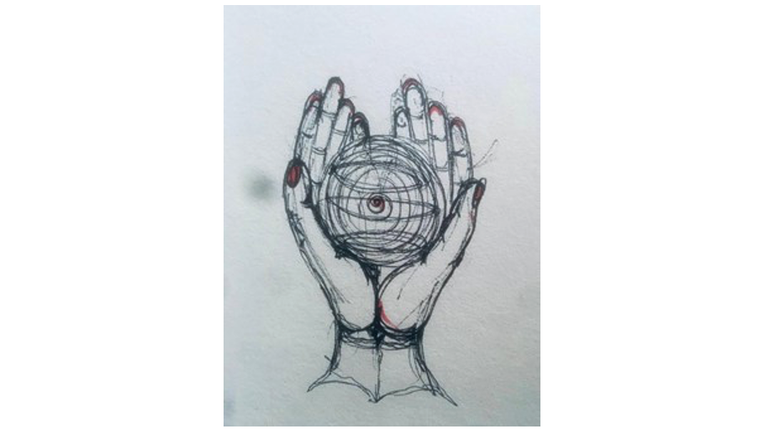

A few evenings later, I receive the following pen-marker sketch from Nkurunziza:

Below the sketch is the following message: “Dear Aalyia, I offer you a rough sketch of hands. Hands hold our past, present, and future energies. They hold all life. Do you agree? Cheers!”

I am transfixed with Nkurunziza’s bespoke sketch. Zooming in and out and then gliding over specific sections of the sketch, such as the tips of the fingers, wrists, and palms where the use of black and red ink is more pronounced, I imagine Nkurunziza working away in the depths of the night with his cat, Korona, by his side, in his studio Inema Arts Center, an institution he co-founded with his brother Emmanuel Nkuranga. My gaze then rests on the sphere-like object that sits delicately between the pair of hands, an object that suggests a certain cosmic energy. Its core, marked with a red dot at the end (or beginning?) of the spiral, is absorbing and radiating energy from the hands. The sketch stimulates a sense that hands are responsible for producing, mediating, and protecting the energy of the spinning sphere. Nkurunziza’s hands are his creative tools. They connect him to the cosmos, allowing him to travel through space and time according to his own pace. Hands are spellbindingly powerful. In Nkurunziza’s precise words, they “hold all life.”

Ibiganza (hands in Kinyarwanda) are powerful symbols of contemporary history and everyday social life in Rwanda. In my ethnographic research on aging, care, and kinship, hands are frequently invoked in conversation—or used through gesture—to narrate various chapters of Rwandans’ lives (or the lives of their kin) across time. For many, hands elicit troubling memories of conflict, violence, and social rupture. As I have often heard in my conversations with Rwandans young and old over the years, hands are the appendages that overturned the nature of social relationships that ultimately dismantled the architecture of trust in Rwandan society. At the same time, hands also have the power to change the course of the present, one that is configured as a precursor by many to an open future. Emphasized in the Kinyarwandan saying, amateka y’igihugu aturi mu biganza (our history is in our hands)—hands like people—are not necessarily prisoners of the past. They take on critical roles in fostering healing and nurturing trust—be it through engaging in everyday collective practices of land cultivation and intimate care, such as bathing, dressing, feeding, and toileting—which bring Rwandans “face-to-face” (Lévinas 1969), not just with the earth and those around them, but also with themselves.

Today, hands in Rwanda point to a time undergoing intense cultural and digital change. Increased government investment in digital technologies—such as “momo” (mobile money) apps, smart-card ticketing systems, and data-driven startup companies—is producing a digit-al economy in which hands, especially those of the youth, are acquiring a new repertoire of skills that fall under the broad rubric of African innovation and social transformation. In the words of a graduate of the Carnegie Mellon University in Rwanda and self-identified “Afro-techie,” who I met during a virtual meet-and-greet event organized by the Knowledge Lab (also known as KLab) in Kigali in February 2018, “I am now producing code for a cyber-security firm and managing software organization tracking farmers’ labor output with a touch of a finger.”

Despite its promissory qualities, Rwanda’s emergent digit-al revolution, which its proponents hope will turn the country into a high-tech regional hub akin to Singapore, raises various questions about what is gained and lost in the quest for technological prowess. To make sense of these emergent shifts, I am reminded of the Rwandan notion of utuntu duto (small things). Although introduced to me by abasaza (members of the elderly generation) in the context of everyday intimate care, considered the most delicate due to the affective investment it embodies and physical vulnerabilities it exposes (Sadruddin 2020), the phrase can also be used to think through general actions that imbue everyday life with meaning and dignity. From shaking the hand of a neighbor to tilling the land, washing an aging or ailing body to blessing a newborn baby, the very foundation of human and earthly life rests on the principal of doing small things with and for each other, day in and day out. What, then, is at stake when the roles of hands migrate from one digit-al interface to another? How do people, for whom matters of intimacy and trust stem from being in the physical company of kin, navigate these burgeoning worlds? Can small things harbor the same (or perhaps a different) affect in digitalized spaces?

The actions and practices of hands are conduits for theory production. Through hands, we can trace and learn about a nation’s collective biography. As physical touch becomes more elusive in a rapidly digital world, Rwandans’ relationships with technology are etched in ambivalence. As one elderly woman mentioned in a conversation, “We are now a part of a big world. I do not fear technology. I fear the death of the most basic things we Rwandans have done for generations like shake hands and sit with our family members.”

Imprinted in the story of hands, then, is the notion of ubuzima (life). To circle back to Nkurunziza’s statement, “hands hold all life.” From digit-al to digital, the moral economy of hands in contemporary Rwanda reveals the gains and losses that accompany the embrace of techno-forms of life.

[1] To learn more about Nkurunziza’s and his team’s art visit: https://www.inemaartcenter.com.

Lévinas, Emmanuel. 1969. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh, Penn.: Duquesne Press

Sadruddin, Aalyia Feroz Ali. 2020. “The Care of ‘Small Things’: Aging and Dignity in Rwanda.” Medical Anthropology 39, no. 1: 83–95.