HandsOn Time

From the Series: HandsOn: Touching the Digital Planet

From the Series: HandsOn: Touching the Digital Planet

In the palms of her hands, Amelia lets her smartphone rest, a gentle embrace. Her thumbs, taking turns, tap the screen at a rhythmic pace. I observe her on my laptop at my kitchen table, as she sits in her military bunkbed miles away. Amelia keeps our conversation going, while texting her boyfriend. I know she cannot see me. With a finger I am swept aside, hidden on her mobile screen. This move enables her to be present two different places at once with two different people who neither see nor participate in each other’s conversations with her. That is, I somewhat participate in her engagement with him, as I see her fingers smoothly maneuver the buttons on her phone. I observe how her fingers communicate words different from those spoken to me. In a couple of minutes, her thumb swipes me back onto her screen. She smiles and lets me know that she just had to let him know she is talking to me.

It’s evident that Amelia and Pete communicate not only through their phones, because behind her is a corkboard crowded with letters, cards, and pictures of and from Pete. Somewhere into our conversation she pauses, and comments on texting and receiving digital pictures. A text message cannot be compared to a handwritten letter or card, she argues. Why is this so? I wonder. “Time,” she replies. “Time?” I ask.

According to Thorheim (2009) all existence, changes, all processes in humans, nature, and environments must be understood in the light of time. Time differs, in measures and in experience depending on our mode of travel, on how we move through the world. Depending on how we hold or let time slip through our fingers.

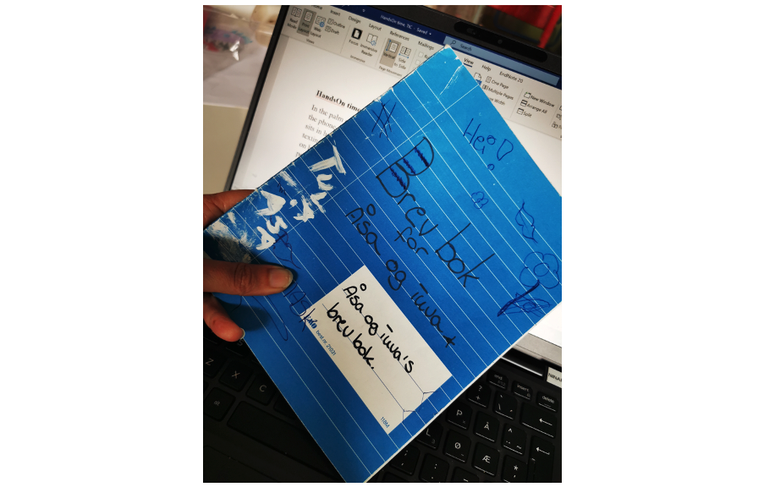

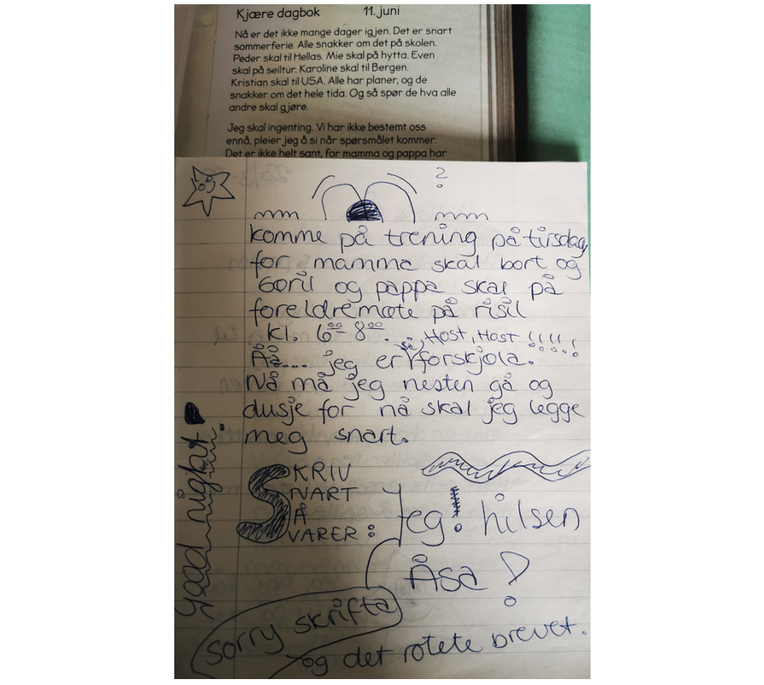

Some time had passed when I found myself unpacking after relocation—emptying cardboard boxes as I lifted one book after the other, finding a place for them on the bookshelves. There is an old pupil’s notebook, with a white-lined, blue soft wrinkled cover. Youthful handwritten letters spell my best friend’s name and mine:

It was not written with my best letters. I remember the book meant a lot to me back then. I assume it was a manifestation of our friendship, a shared diary. We each were supposed to keep it two weeks, tops, then swap, sharing gossip, our thoughts, and wonders. My hands hold this treasure for a while—the front cover, a handcrafted mess. How strange to feel how time has passed, yet very much alive.

Turning the pages, I discover that letters like time achieve their meaning through travel mode. How have our conceptions of time changed since Åsa and I created this book? Or have they? Words travel fast these days! Da Vinci believed that a real painter was one who thinks with his hands. Michelangelo did not agree, thus arguing that a man paints with his brains not with his hands. I root for da Vinci. Letters and this specific diary are a piece of artwork—every single alphabetical character. They are not crafted by the brain (alone), but felt and crafted by a hand firing it off, sending signals, fingers squishing a pencil, a hand pushing hard or gently moving while touching a paper surface—all movements that with time are internalized and embodied (Mauss 2004 [1979]). Following Thorheim (2009), time and being are inseparable.

Time spent on epistolary writing and scribbling has greater value than on typing, says Amelia.

The letters in the diary convey both fast and slow writing. It is obvious where we hurried and where we spent devoted time. As I read, I clearly see that we both, even then, knew that our handwriting revealed our state of mind and time. On every third page or so, we write:

sometimes accompanied by an explanation:

Handwriting consumes time, requires cleared time. You cannot write a letter standing up, walking the streets, at least I cannot. But a message of care, a thumbs up in support is doable. Handwritten letters cannot compete with tapping or swiping letters on a phone screen. As a result, handwriting, slow-writing, has become a rarity (Garfield 2013). So has the little blue book in my hand.

I know Amelia has her own shared diary, hidden on her phone. The thread of messages between her and Pete seems endless. She has kept the very first text she received from him three years ago. She has several diaries, with several people, on her phone. Each time she sends a picture or a message, she knows when the receiver opens it, and she expects an answer or some sort of sign—like a heart or a thumbs up. A touch of the send button is all it takes, a touch of attention. Amelia grew up in an information era—an age in which hands are expected to work fast. If they don’t work fast, our hands might get replaced or highly disappoint others.

Reactions, gossip, and pictures travel fast by touch. Often short-lived, a text is meant for the moment. Couples may keep their conversations for years. Even after disposing of the phone, content can be transferred. However, the day you abandon your once beloved, the phone dies—the conversations most likely die with it. Handcrafted messages are often made to last, and that is why a youngster self-excused her handwriting. To you who read it now, to you who might read it in the future, I could have done better. A piece of me is left behind, exposed by words and handwriting style.

The handwritten is an epitome of care: You are worthy of my time.

My index finger trances shared words in our diary. I am going to hold on to it a bit longer. I am HandsOn time, a time crafted with pondering, youthfulness, and friendship. I am HandsOn a time I took for granted then, the handwritten that is the slow hand. A slow hand that Amelia granted value: “Just knowing he took the time to sit down and write to me. That means so much more than that quick text.” The handcrafted letters, slow writing, and exposure of personality is hidden in autocorrected machine-typed letters. Identically looking characters punched into existence by moving fingertips, not by a hand holding a pencil, transmitting germs, odors, and love. Handwritten and held, instead of hidden in an untouchable cloud.

Garfield, Simon. 2013. “To the Letter : A Celebration of the Lost Art of Letter Writing.” New York: Penguin.

Mauss, Marcel. 2004 [1979]. Kropp og person: to essays [Body and Person: Two Essays]. Vol. 46. Les techniques du corps. Translated by Iver B. Neumann. Oslo, Norway: Cappelen akademisk forlag.

Thorheim, Kirsti Mathilde. 2009. Tid blir ikke borte: et øyeblikk! Så lenge det varer [Time does not disappear: a moment! As long as it lasts]. Oslo, Norway: Cappelen Damm.