I’m (Not) Green

From the Series: Substitution

From the Series: Substitution

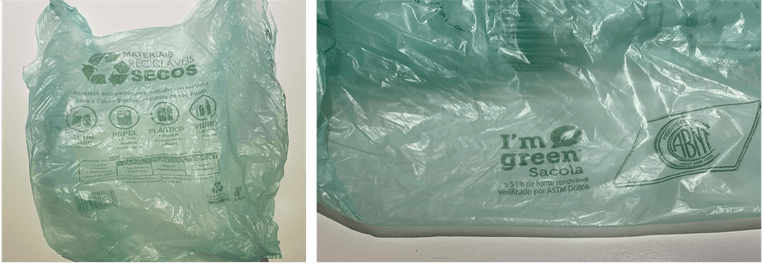

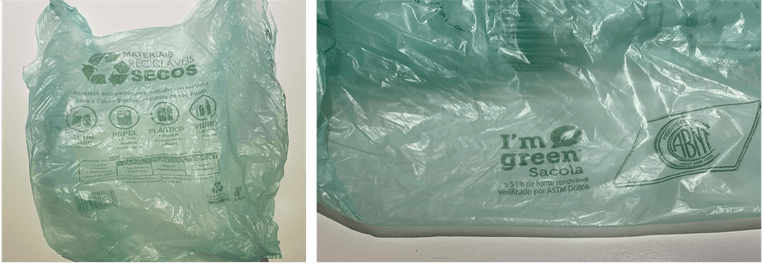

When I go to the grocery store in São Paulo and check out, I can pay a few cents extra to get a plastic bag. I’ve learned to look closely at labels on plastic things in Brazil, and sure enough, on the side of these plastic bags is a tiny graphic logo with the words, “I’m green,” in English. This logo belongs to a large Brazilian petrochemical company, which for almost a decade has been making some of their plastic products from sugarcane, indicated by this “I’m green” logo.

The logo utilizes the connotation of “green” with environmentally friendly renewables. Many people would understandably assume that this green, sugarcane-based bioplastic is better for the environment—for example, that because it’s made from plants, the plastic is biodegradable and doesn’t clog up landfills or choke marine ecosystems.

However, these sugarcane-based bioplastics are not biodegradable. Perhaps surprisingly, they’re chemically and structurally identical to petro-based plastic, which is decidedly non-biodegradable (at least on relevant time scales). The actual difference between conventional plastic and this sugarcane-based bioplastic, then, is the source of its carbon molecules—plants versus petroleum. One can make plant-based plastic that is in fact biodegradable, but this is not an inherent quality of bioplastic merely because the source of the carbon is plants.

These non-biodegradable sugarcane–based bags, on the other hand, mostly end up in landfills after being re-used to collect household trash or recyclables. Consumers often get new bioplastic bags each time they go to the store. Many people don’t even realize these bags are made from sugarcane.

These bags have stuck with me as a reminder of the paradoxes of substituting sugarcane for petroleum. A good substitute should be similar to the original; this is why it’s a substitute and not an altogether new thing. But, the sugar-based bioplastic above seems too similar. Do we really want to keep the non-degradability of petro-based plastic? Do we want to keep the industrial norm of promoting single-use, disposable plastic for purposes that don’t actually require disposability? How do we decide what should be similar, and what should be different, when it comes to renewable products and strategies for energy transition in general? Which differences might actually make a difference (Ballestero 2019) when it comes to mitigating environmental and social harm?

This essay takes up this interplay between similarity and difference in what I’ve described as the substitutive politics of sugarcane-based renewables in Brazil (Ulrich 2023). Substitution articulates both similarity and difference. I use “substitution” to flag problematic practices within environmental efforts of keeping petro-extractivist relations the same while displacing difference onto other sites, such as the particular site or source of carbon.

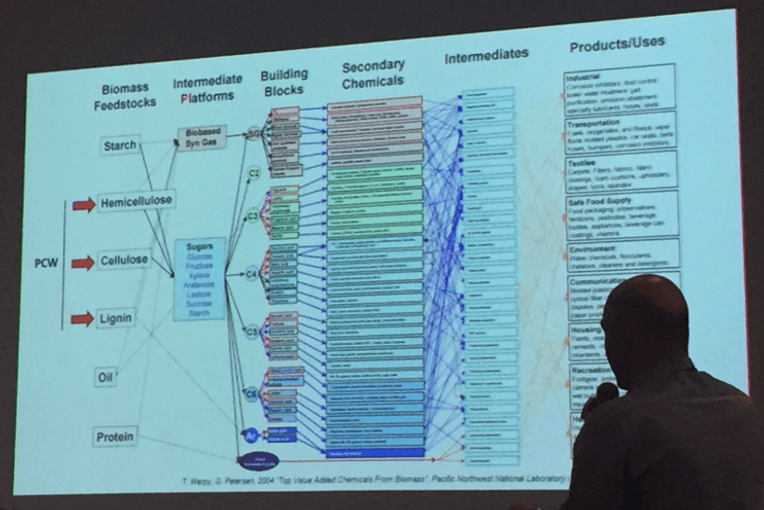

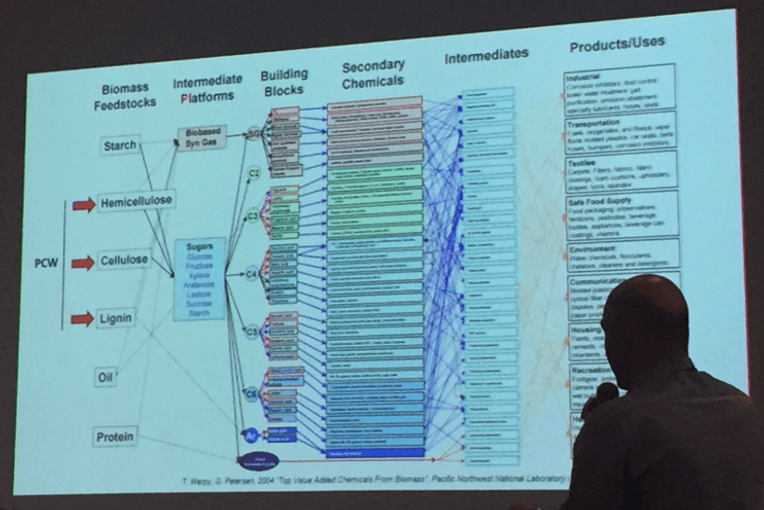

Such substitutive politics of green technologies are visually reflected in another fieldwork moment. My research was primarily with scientists and engineers in the state of São Paulo, and I spent time in their labs as well as attended conferences and events. At one workshop on plant engineering, a scientist who studies plant-based renewables presented a striking diagram.

As he explained, the diagram depicts biomass—including plants like sugarcane—as an industry input. The diagram starts with biomass on the left and branches to the right with various byproducts and subproducts obtained from biomass. It keeps branching into increasingly finer outgrowths, dozens of them, to show the vast array of end-products potentially made from biomass. These end-products are listed in tiny font that was nearly impossible to read at the event. Still, the diagram’s visual argument remained legible: biomass such as sugarcane can serve as an input for a vast array of products, from fuels to plastics to industry solvents. As an input, sugarcane biomass’s value is its ability to become almost anything.

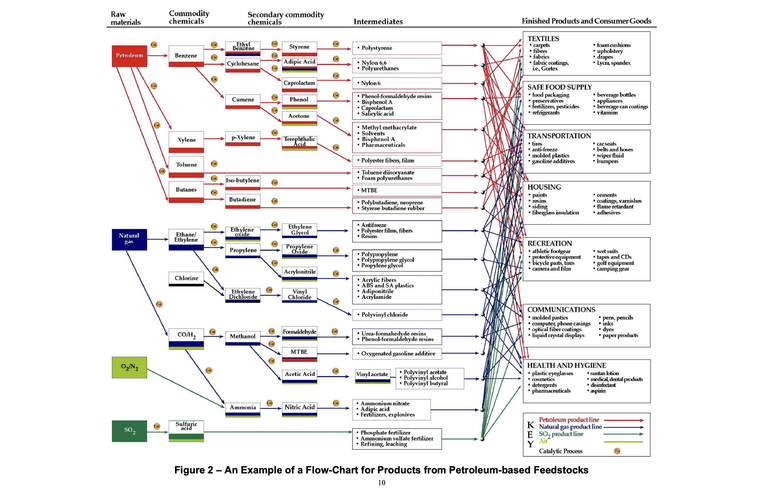

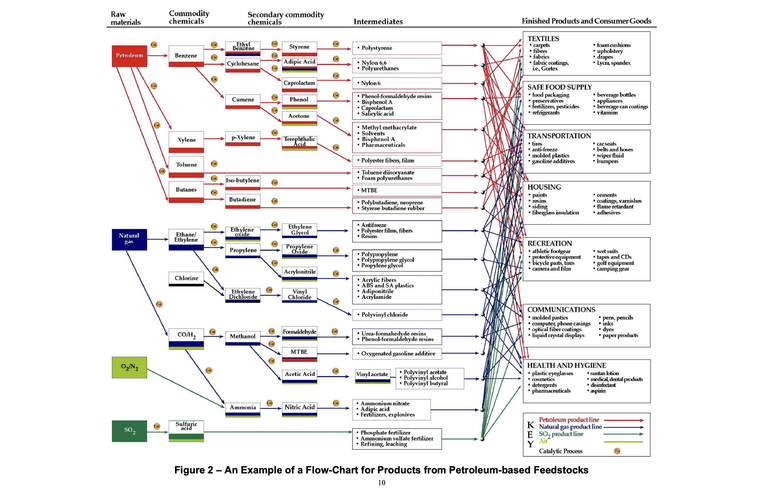

Yet the moment when this chart really sparked my ethnographic curiosity was a few years later, when I looked online for a higher-quality version to use in a talk. I was intrigued to instead find a very similar diagram—but with petroleum as the input.

I suggest it’s not an accident that the biomass version looks so similar to the original petroleum version. Indeed, the presenter said repeatedly that biomass can substitute (substituir) for fossil fuels. These diagrams demonstrate, formally, renewable substitution logics. The formal structure of the diagram—the branching that represents how one input can become myriad products—stays the same, while the input can be different. In other words, the petro characteristic of making a seemingly endless array of things, and the value attached to this infiniteness, remains.

Not surprisingly then, the actors spending the most money researching renewables like bioplastic (as well as biofuels) are large oil and gas companies. Such convergences between petro and renewables can seem surprising or paradoxical, but a growing literature examines the contradictions of green energy projects and “green capitalism” (see for example Howe 2019, Boyer 2019, Ahmann 2019, Kaşdoğan 2020, Günel 2019, Cross 2019, Folch 2019, Jobson 2020, and Caporusso 2019).

Ultimately, if sugarcane-based renewables offer a pathway to post-petroleum futures, as many proponents argue, the ghost of petroleum lingers in this post-petroleum formulation. Sugar-based replacements seek to replicate and copy what petroleum has provided; the original haunts the copy. Petro-extractivism—which, after all, extends far beyond the technical extraction of oil to certain growth-obsessed, imperial-colonial social systems (Marques 2018)—endures.

Petro-capitalism was in turn built on the slavery-based economies of sugarcane plantations, and early synthetic plastics were substitutes for natural materials, like ivory; there are multiple layers of substitution happening here. How would our conceptual frameworks around renewables shift if we considered fossil fuels as themselves substitutes, not the original?

Substitution proves both material and conceptual, masquerading the continuity of ideological and molecular status quos behind the idea of desirable (“green”) difference.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (GRFP 1842494 and BCS-1918156), the Brazilian Studies Association, and Rice University. Thanks to Helena Fietz for her attentive and insightful editorial work on the Portuguese translation of this text.

Quando vou ao supermercado em São Paulo e finalizo a compra, tenho a opção de pagar alguns centavos a mais para receber uma sacolinha plástica. Ao longo dos anos, aprendi a olhar atentamente para os rótulos dos produtos feitos com plástico no Brasil e, invariavelmente, nessas sacolinhas plásticas há um pequeno logotipo gráfico com as palavras, "I'm green" (“sou verde”). O logotipo é de uma grande empresa petroquímica brasileira, que há quase uma década fabrica alguns de seus produtos plásticos não a partir do petróleo, mas da cana-de-açúcar. Daí o dizer, "I'm green."

O logotipo utiliza a conotação de "verde" com energias renováveis ecologicamente corretas. É compreensível, portanto, que muitas pessoas presumam que este bioplástico verde, à base de cana-de-açúcar, seja melhor para o meio ambiente. Como, por exemplo, que, por ser feito de plantas, este plástico seja biodegradável e não obstrua aterros nem sufoque ecossistemas marinhos.

Ocorre que esses bioplásticos de cana-de-açúcar não são biodegradáveis. Talvez para a surpresa de muitos, eles são quimicamente e estruturalmente idênticos ao plástico de base petroquímica, o qual definitivamente não é biodegradável (pelo menos não em escalas de tempo relevantes). Assim, a diferença de fato entre o plástico convencional e o bioplástico feito com cana-de-açúcar é a fonte das suas moléculas de carbono—plantas ou petróleo. Ainda que seja possível fazer um plástico a base de plantas realmente biodegradável, esta não é uma qualidade inerente ao bioplástico apenas por sua fonte do carbono serem plantas.

As sacolinhas não biodegradáveis feitas a partir de cana-de-açúcar, por sua vez, com frequência vão parar em aterros sanitários após serem reutilizadas para coleta de lixo doméstico orgânico ou reciclável. Os consumidores costumam receber novas sacolinhas bioplásticas cada vez que vão à loja e muitos sequer percebem que as sacolinhas são feitas de cana-de-açúcar.

Essas sacolinhas ficaram comigo como um lembrete dos paradoxos da substituição do petróleo pela cana-de-açúcar. Um bom substituto deve ser semelhante ao original; é por isso que é um substituto e não uma coisa totalmente nova. Mas, o bioplástico à base de açúcar sobre o qual falei acima parece semelhante demais. Queremos realmente manter a não-degradabilidade do plástico derivado do petróleo? Queremos seguir a norma industrial de promover o plástico descartável de utilização única mesmo quando ser descartável não seja necessário? Como decidimos o que deve ser semelhante e o que deve ser diferente em se tratando de produtos renováveis e estratégias para a transição energética em geral? Quais diferenças podem fazer, na verdade, a diferença (Ballestero 2019) no contexto de mitigar os danos ambientais e sociais?

Este ensaio aborda essa interação entre semelhança e diferença naquilo que descrevi como a política substitutiva das renováveis[1] baseadas na cana-de-açúcar no Brasil (Ulrich 2023). A substituição articula semelhança e diferença. Eu uso "substituição" para sinalizar práticas problemáticas dentro dos esforços ambientais de manter as mesmas relações petroextrativistas enquanto desloca a diferença para outros locais, como o local ou fonte de carbono.

Essa política substitutiva das tecnologias verdes se reflete visualmente em outro momento do trabalho de campo. Minha pesquisa se deu principalmente com cientistas e engenheiros do estado de São Paulo, com quem passei algum tempo em seus laboratórios e também participei de congressos e eventos. Num workshop sobre engenharia de plantas, um cientista que estuda combustíveis renováveis derivados das plantas apresentou um diagrama impressionante.

Como ele explicou, o diagrama representa a biomassa—incluindo plantas como cana-de-açúcar—como um insumo industrial. O diagrama começa com a biomassa à esquerda e ramifica-se à direita com vários subprodutos obtidos desta. Ele continua a ramificar-se em extensões cada vez mais finas, dezenas delas, para mostrar a vasta gama de produtos finais potencialmente feitos a partir da biomassa. Esses produtos finais estão listados em letras minúsculas quase impossíveis de ler durante o evento. Ainda assim, o argumento visual do diagrama foi legível: biomassa, como a cana-de-açúcar, pode servir como insumo para uma vasta gama de produtos, desde os combustíveis aos plásticos aos solventes industriais. Como insumo, o valor da biomassa de cana-de-açúcar é sua capacidade de se transformar em quase tudo.

No entanto, foi alguns anos mais tarde quando procurei na internet uma versão de maior qualidade para que pudesse usar em uma palestra que este diagrama despertou a minha curiosidade etnográfica. Isso porque, foi intrigante encontrar um diagrama muito semelhante, porém com o petróleo como o insumo em destaque.

Sugiro não ser por acaso que o diagrama de biomassa seja muito parecido com a versão original de petróleo. De fato, o palestrante afirmou repetidamente que a biomassa pode "substituir" os combustíveis fósseis. Estes diagramas demonstram, de modo formal, as lógicas da substituição renovável. A estrutura formal do diagrama—a ramificação que representa como um insumo pode se transformar em uma miríade de produtos—permanece a mesma, enquanto o insumo pode ser diferente. Em outras palavras, a característica petro de produzir uma variedade aparentemente interminável de coisas—e o valor atribuído a esta infinidade—permanece.

Não é surpreendente, portanto, que os atores que gastam mais dinheiro em pesquisa com renováveis como os bioplásticos (e também os biocombustíveis) seja grandes empresas de petróleo e gás. Tais convergências entre o petróleo e os renováveis podem parecer surpreendentes ou paradoxais. No entanto, há uma literatura cada vez mais expressiva examinando as contradições de projetos de energia verde e do "capitalismo verde" (veja por exemplo Howe 2019, Boyer 2019, Ahmann 2019, Kaşdoğan 2020, Günel 2019, Cross 2019, Folch 2019, Jobson 2020, e Caporusso 2019).

Enfim, se os renováveis derivados de cana-de-açúcar oferecem um caminho para futuros pós-petróleo, como argumentam muitos de seus proponentes, o fantasma do petróleo permanece nesta formulação pós-petróleo. Os substitutos à base de açúcar querem replicar e copiar o que o petróleo forneceu: o original assombra a cópia. O petro-extrativismo—que, afinal, se estende muito além da extração técnica de petróleo aos sistemas sociais imperial-coloniais obcecados pelo crescimento (Marques 2018)—perdura.

O petrocapitalismo, por sua vez, foi construído sobre as economias baseadas na escravatura das plantações de cana-de-açúcar, e os primeiros plásticos sintéticos substituíram materiais naturais, como o marfim. Existem inúmeras camadas de substituição acontecendo aqui. De que forma nossos quadros conceituais sobre os renováveis mudariam se considerássemos os combustíveis fósseis como os substitutos e não como os originais?

A substituição é material e conceitual, mascarando a continuidade do status quo ideológicos e moleculares por detrás da ideia da desejável diferença "verde."

[1] Por exemplo, combustíveis renováveis e materiais renováveis.

Esta pesquisa foi apoiada pela National Science Foundation dos EUA (GRFP 1842494 e BCS-1918156), pela Brazilian Studies Association, e pela Rice University. Obrigada a Helena Fietz pelo seu trabalho editorial atento e perspicaz nesta tradução.

Ahmann, Chloe. 2019. “Waste to Energy: Garbage Prospects and Subjunctive Politics in Late-Industrial Baltimore.” American Ethnologist 46, no. 3: 328–42.

Ballestero, Andrea. 2019. A Future History of Water. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Boyer, Dominic. 2019. Energopolitics: Wind and Power in the Anthropocene. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Caporusso, Jessica. 2019. “The State of Energy: Material Dimensions of ‘Dirty’ Renewables in Mauritius.” Shoring: The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, 4: 18-19.

Cross, Jamie. 2019. “The Solar Good: Energy Ethics in Poor Markets.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 25 no. S1: 47–66.

Folch, Christine. 2019. Hydropolitics: The Itaipu Dam, Sovereignty, and the Engineering of Modern South America. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Günel, Gökçe. 2019. Spaceship in the Desert: Energy, Climate Change, and Urban Design in Abu Dhabi. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Howe, Cymene. 2019. Ecologics: Wind and Power in the Anthropocene. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Jobson, Ryan Cecil. 2020. “The Case for Letting Anthropology Burn: Sociocultural Anthropology in 2019.” American Anthropologist 122, no. 2: 259–271.

Kaşdoğan, Duygu. 2020. “Designing Sustainability in Blues: The Limits of Technospatial Growth Imaginaries.” Sustainability Science 15, no. 1: 145–160.

Marques, Luiz. 2018. Capitalismo e Colapso Ambiental. Third edition. Campinas, Brazil: Editora da Unicamp.

Ulrich, Katie. 2023. “The Substitute and the Excuse: Growing Sustainability, Growing Sugarcane in São Paulo, Brazil.” Cultural Anthropology 38, no. 4: 439–466.