Introduction: Counter Archives

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

Three co-editors put this special issue together. Two remain anonymous due to the unevenly distributed repression that places them at greater risk.

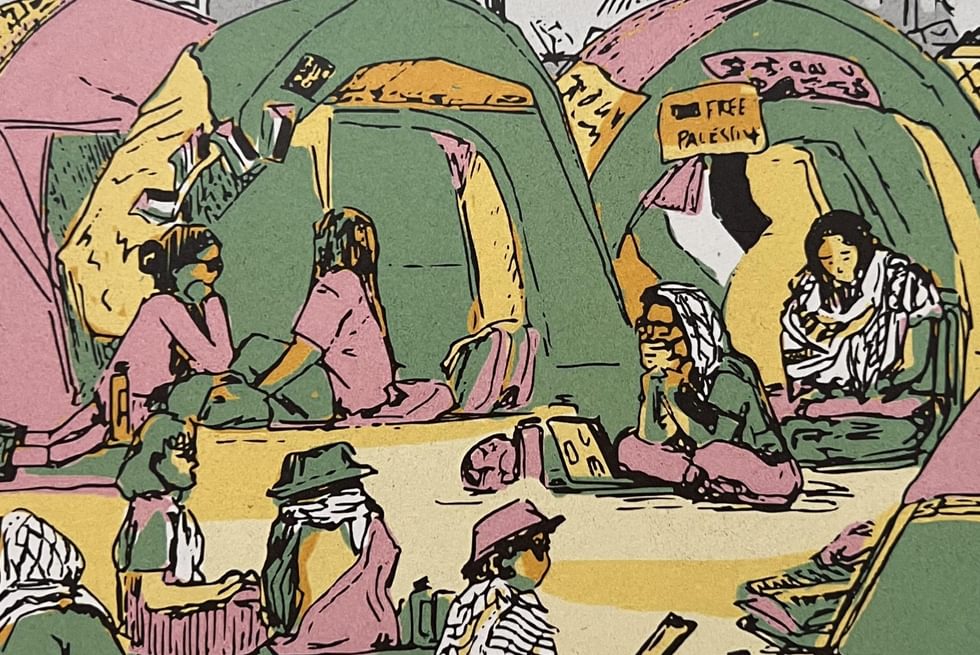

In the weeks and months after Israel’s U.S.-supported war in Gaza began in October 2023, groups of students began pitching tents on college campus lawns across the United States and the world, demanding a ceasefire and divestment from military companies. These encampments, escalating in April 2024 in the United States, were the crest of months of student activism opposing Israel’s occupation, war, and genocide—campus activism that was arguably the most significant in a generation, at least in the United States, leading to highly-politicized Congressional scrutiny and downfall of elite university presidents. Perhaps inevitably, given the intensifying censure of pro-Palestinian activism throughout the academic year, the encampments were cynically tarred as anti-Jewish, and provoked bipartisan condemnation demanding that students and faculty be punished, or federal funding would be withdrawn. The initial encampments—some spare, others sprawling—were met with swift and often violent campus and city police responses. Others endured longer before eventually succumbing to dismantlement.

At the University of Rochester, a day after its demolition, rectangular browned patches of flattened grass in two concentric circles on the main academic quad indexed the encampment’s vibrant sociality. The reseeding solution sprayed on the soil underscored official efforts to overwrite and erase it. By a week later—uncoincidentally, the day after graduation ceremonies concluded—groundskeepers dug up the entire portion of lawn, replacing it with rolls and rolls of prefab sod. By early summer, the physical traces of Camp Resilience were gone.

This collection proposes to join these lingering tent footprints as forms of counter-archiving, seeking to recover traces of these embodied, ephemeral encampments, as a new academic year in the United States has begun with new restrictions on protest (and even the firing of a pro-Palestine faculty member), and as Israel’s devastating war and genocide in Gaza continues and expands, most recently and destructively in the West Bank and Lebanon. Informed by decolonial feminist practices designed to disrupt the dominant narrative, we produce this counter-archive to refuse the neutralization and attempted return to the status quo ante that the erasure of encampments seeks to enact.

We do so to examine and reclaim the potentialities within coalitional student-centered world-making and protest against state violence—activism that was violently destroyed in patterned ways across the country and the world, activism that was disciplined through university procedures that evacuated its political content in an effort to neutralize its power, activism that was used as a pawn by national and global antidemocratic authoritarian politics to consolidate power, activism that, we believe, is a necessary—though clearly insufficient—response to the war and genocide in Gaza.

There is an inherent tension in this effort, as George Bajalia reminds us, between here (the imperial core) and there (its colonial outposts), and a caution against letting dynamics of university campuses distract focus from stopping the ongoing genocide in Gaza. (“Why are we talking about dead grass, not dead children?” a reader might ask.) These are thorny question at the core of anthropology as a discipline: how do we teach and engage with there from here, without simply recentering the imperial core?

We foreground the encampments ethnographically here as instructors (adjuncts, lecturers, visiting professors, untenured assistant professors, tenured professors) and students (undergraduate and graduate) who participated in them, because they provided a glimpse of what critically engaged teaching and learning can be. They provide models, perhaps, of how to hold people here accountable to the there where there is both a particular occupied territory under siege and genocide, and also a set of structuring global conditions including U.S. empire and militarization, settler colonialism, and global capitalism. They suggest the kinds of capacious, courageous solidarity and action that might move beyond constraints of identity politics. This counter-archive thus is intended to sit alongside ongoing writings by people in and of Palestine, within and outside the academy, demanding ceasefire, end of occupation, and liberation.

This counter-archive refuses the prevailing frame in which pro-Palestinian speech and action is inherently dangerous, violent, or antisemitic. It speaks intentionally against pervasive characterizations of encampments in U.S. media and politics that see activist students as the core problem, characterizations that distract public attention from both the outsized dehumanization of the American-supported Israeli war machine, and from the twinned anti-democratic crises of authoritarianism and anti-intellectualism in the United States. The counter-archive presents emic perspectives and theorizations that contextualize these encampments nationally and globally as form and event, and within broader histories of racist policing of student protest. The counter-archive thus seeks to interrupt the purported inevitability of occupation, war, and genocide.

The essays as counter-archive intentionally refuse the conventional academic form. They center writing, drawing, photographing, mapping, videoing, audio recording, all practices intertwined with the embodied practice of being in the encampment. They are collaborative and multi-vocal. They include an overflow of images. They center description over didactic argument. “I am aware it's not particularly analytical but I hope it conveys well what happened at our campus,” wrote one contributor, echoing others, as he submitted his essay. They are fieldnotes from the encampments.

The collection’s emphasis on the United States and specifically New York State is an artefact of how the collection emerged: beginning with conversations among faculty located on campuses in New York, then circulating as an open call through trusted colleagues and activist networks on Signal, reaching across North America, into Europe and the Middle East. As summer wore on, several intended contributors reached out with apologies—they didn’t have the emotional or physical energy to write in the face of ongoing violence, or didn’t have the time while still protesting or fighting disciplinary proceedings. The skewing of the resulting submissions points to the labor and life conditions at the core of the collection: Who has the capacity to protest? Who can write about protest? What is the purpose of academic writing anyway? The condition of possibility for the essays included here are the earliest encampments on the west coast, building from work by coalitions of working-class students at public and private colleges who strategically and creatively linked localized struggles in communication and solidarity with students across the country, and with Palestinians and now with Lebanese, long before the national media fixated on New York City and elite private institutions.

But the focus on the United States and New York also reflects, like the demands of the encampments themselves, the need to confront the bipartisan U.S. material and ideological support for the siege on Gaza and now the invasion of Lebanon. The United States and Germany, also represented in the collection, are the top two weapons suppliers and two main states that manufacture consent for genocide. The submissions that extend outside the United States invite us to begin to consider how encampments varied based on national and regional politics. Overall, these contributions are but one fragmented piece of a counter-archive that lives also on Instagram accounts for, for example, Students for Justice in Palestine, Jewish Voice for Peace, and Students for a Democratic Society among others, in audio and video files on student phones and laptops, in notebooks and sketchbooks, in oral recounting. We see this as a beginning, to be joined by ongoing counter archives of struggle.

We offer the essays here, with authors named or sometimes with pseudonyms or anonymous—as activists themselves were often masked, in a combination of self-protection in the face of the surveillance-state, and in enactment of solidarity with a movement bigger than the individual—in a call to refuse the forces that seek to distract, silence, or neutralize pro-Palestinian speech and activism. We offer them as Israel’s war machine moves once again into Lebanon, a war zone that, as Khayatt writes, “has been at the heart of the geopolitical struggles of the modern Middle East since the inception of the Zionist state of Israel in 1948,” and whose struggles are deeply intertwined with Palestinian liberation.

We offer them here in acknowledgement of the messy, imperfect, but powerful solidarities and collaborations from which encampments emerged and which they enacted, solidarities that are ongoing today despite increasing repression and punishment, and that seem to be essential to the project of both ending the suffering in Gaza and in Lebanon, and to building an alternative future for Palestinian liberation.

Thank you to all the students, faculty, staff, and community activists who supported, participated in, and documented the encampments, and to those who shared their experiences with us all here.