Islands Dropped from a Basket (after Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner)

From the Series: Un/tracing Empire: Pollinations between the Poetic and Ethnographic

From the Series: Un/tracing Empire: Pollinations between the Poetic and Ethnographic

The archives of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) are characterized by certain losses, given the U.S. Cold War penchant for secrecy and redaction. But they are also filled to the brim with bureaucratic excess, what Marshallese poet Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner might call “an ocean of documents.” Contracts and compacts shape Marshallese mobilities in the afterlives of U.S. nuclear weapons testing. Permission slips written and signed by colonial brokers seize Indigenous atolls and deliver them into the hands of the U.S. military. So on and so forth. The TTPI archives produce paper towers of omission, documenting violent dispossession in a mundane register. If we are accustomed to a particular mode of looking, these staggering pillars of record could overtake our entire sightline. The consequences of such oversight elide sources beyond and below the archival horizon.

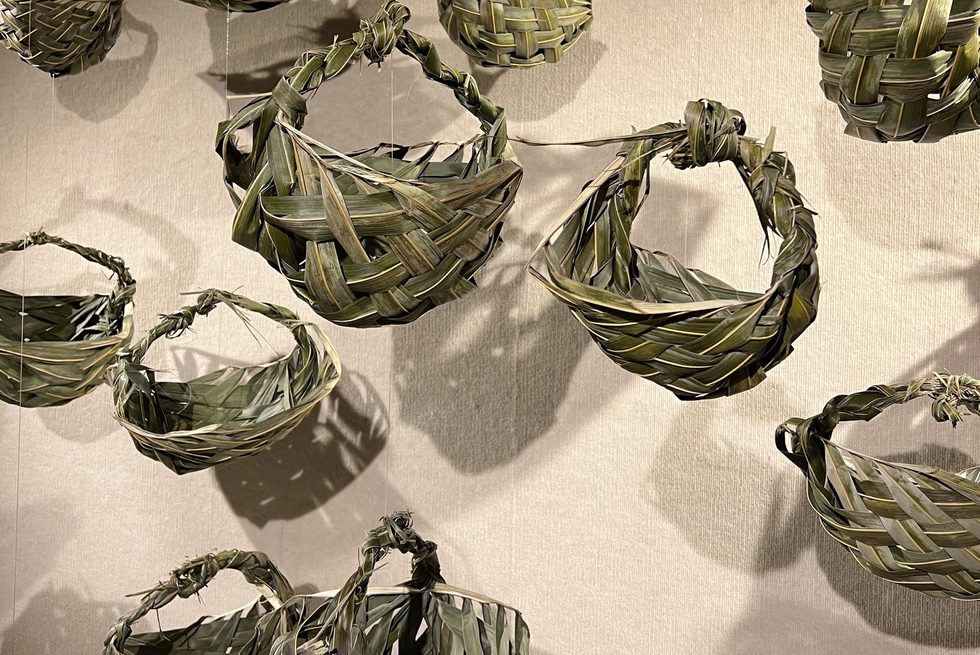

The Marshallese banonoor is one such source. Banonoor are commonly woven with bōb (pandanus leaves) or ni (coconut fronds). These baskets carry multiple registers of significance, filled to the brim with food to welcome new life to this world or guests to one’s home. In a funeral ritual known as eorak, Marshallese use banonoor to collect white stones and then place these stones at the grave of someone with whom they had an unresolved conflict. Eorak allows for the healing of the relationship between the stone gatherer and the deceased. During my fieldwork, I learned how to weave banonoor from a Marshallese women’s group on the Big Island of Hawai‘i, many of whom had migrated multiple times as a result of U.S. nuclear weapons testing in their home islands. Banonoor were the site at which stories were shared and were storied unto themselves. As we pounded the bōb to soften it, weavers shared their experiences of displacement, of reproductive injustice, of navigating bureaucracy, of their desires to return in death to land they could not access while alive. As we learned to lock edges so that the baskets wouldn’t unravel, I learned which women in the collective knew how to weave and which women were teaching the others. Students born from nuclear colonialisms that had disappeared the coconut and pandanus trees from their home islands. Watching which fingers slowed between steps—matching my tempo—was its own kind of telling.

The relationship between texts and textiles is deeply entangled, circulating with older words for weaving, for fabric, for tissue, for spinning. Administrative texts spin particular stories. Redactions collect fragments into haunting tapestries. In a filing cabinet forgotten, water-logged papers fade evidence away. The TTPI archives privilege a textual and terrestrial orientation to the nuclear legacy. But this ocean of documents necessitates submersion rather than skimming the surface. It requires not just an ethnography of the archive, but of the not-archive.

In the not-archive, banonoor account for a nuclear sensorium. Aluminum pans of rice and taro and meat provide sustenance as the weavers make multiple banonoor in quick succession for a gallery installation. Callused hands fumble with new tools, indexing memory and migration. The baskets are strung up, heavy with nuclear colonialism’s inheritances, its rhythms, its ecological toll. Taking the banonoor as text/ile—as source—I am able to see all the more clearly the lives, histories, and places that it holds.

Bio:

Aanchal Saraf is a PhD candidate in Yale University’s American Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies departments. Her dissertation, titled Atomic Afterlives, Pacific Archives: Unsettling the Geographies and Science of Nuclear Colonialism in the Marshall Islands and Hawaiʻi, demonstrates how U.S. Cold War nuclear colonialism continues to shape our cartographic and archival imaginaries of the Pacific, as well as structures academic knowledge production. Her interdisciplinary project engages official archives, Asian American and Pacific Islander cultural production and performance, and ethnography. Her work is supported by the National Science Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and the Social Science Research Council. Her creative and scholarly works have appeared in Literary Hub, Fruit Magazine, The Journal of Transnational American Studies, and Women & Performance, among other publications.