Living with Ashes

From the Series: Firestorm: Critical Approaches to Forest Death and Life

From the Series: Firestorm: Critical Approaches to Forest Death and Life

For many Australians, 2020 began as a year of fire. The bush fires that ripped through the country that year were unprecedented in scale and destruction. Dubbed the “black summer,” this three-month period saw nearly three billion animals killed or displaced, forty-six million acres of forest destroyed, some 3,500 homes lost, and dozens of people injured or killed. In the continent with the highest rate of mammal extinction, over one hundred species already endangered or threatened were driven to the brink of disappearance—the long-footed potoroo, the mouse-sized dunnart, and the grey-barked nightcap oak, among others. Media footage scarred the public with images of scorched koalas, incinerated kangaroos, bloated cattle, blood-red skies, and the worst air pollution the country has seen. Beyond the flames and the smoke and the char, fires lived on in disembodied ways through virtual maps that tracked in real time the relentless proliferation of “hotspots,” or areas of elevated thermal spectral response.

But what worlds are worlded in the aftermath of forest death? Once the spectacular events of flame and fire subside, and media attention shifts to the next crisis, we are left with fire’s powdery remains—a world of ashes. Over the last year, I have been collecting ashes from across various sites in New South Wales, which is the area most directly affected by the fire crisis of 2020 and the state I have lived in for almost six years. Ashes line the shelves and sills of my home—in empty jam jars, cardboard boxes, and vacuum-sealed pouches. Collecting these ashes has become a ritual of remembrance—a way of commemorating the decimation of multispecies lives and futures.

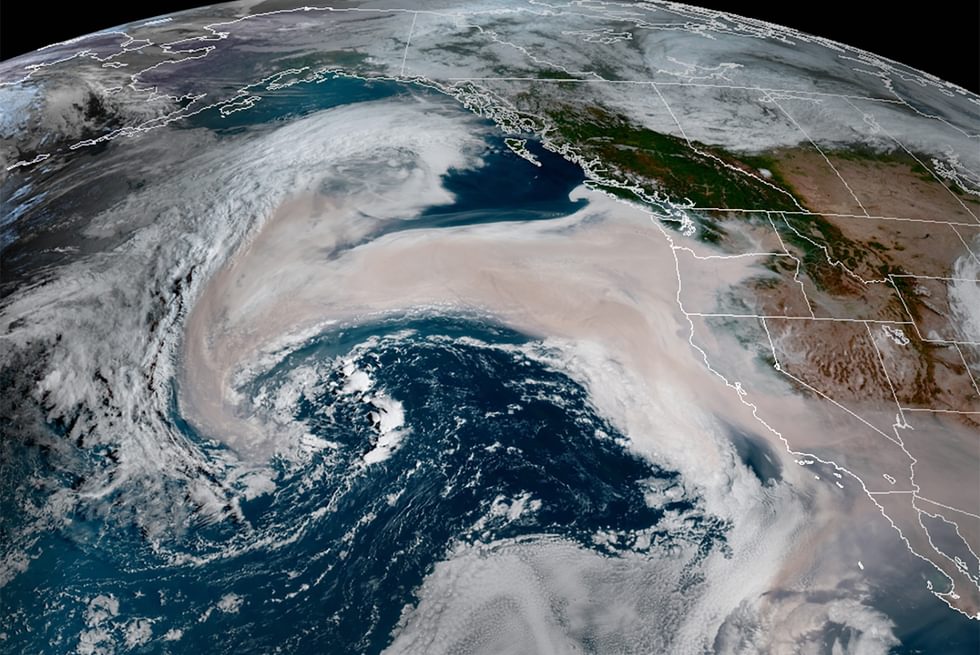

Fire speaks powerfully to the ravaging effects of unsustainable resource extraction on ecosystems and their multispecies communities. Ashes speak in equally meaningful—if less dramatic or eventful ways—to the slow violence of planetary undoings and their latent effects. Ashes are the indistinguishable residues of other-than-human existences. They are the muted embodiments of what has been irrevocably obliterated and what remains of once-lively more-than-human worlds. In ashes are lumped the being of beings no longer individuated or identifiable, and yet all somehow still there, dismembered and conflated, in a dispersed, unrecognizable, dusty mass. Ashes become part of our bodies when we breathe the smoky air around us. The simplest act of survival—breathing—thus makes us unsuspecting conspirers in a deadly, atmospheric communion with multispecies extinguishings.

Living in the aftermath of fire requires thinking and staying with ashes—with what was and what remains. Ashes conjure the indiscriminate destruction of life that combustion—intended and unintended, industrial and metabolic—depends upon. Ashes will scatter across land and water, human and nonhuman bodies, settling in other lands and lives, carrying with them distant deaths and suffering. We may escape the flames, but we must not evade the ashes. Staying with ashes is a way of mourning endings, without resigning to them. What I call for here is a practice of active resistance, remembrance, and grieving—with and through the ephemeral residues of frittered multispecies futures.

At the same time, resisting, remembering, and grieving with ashes reminds us that ashes constitute both the end of some lives and the nourishing grounds of others. In Western hermeneutics, ashes have long been a symbol of death, but also of transformative rebirth. In ecological terms, ashes contribute to water pollution, excess algal growth, and the asphyxiation of fish and other marine life, but they are also rich in nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. In the right quantities, they can help regenerate soils, species, and ecosystems. Ashes, then, are symptoms of destruction—but, like fire, they can also be creative forces that enable the emergence of new and different communities of life. Ashes, in other words, are pharmakonic.

Many such communities of life have flourished across Australia since the black summer of 2020. Juicy, green shoots have sprung from the charred branches of towering gum trees. Epiphytes crawl up and along their trunks, while scribbly gum moth larvae resume their labyrinthine journey along their bark. Species believed to have gone extinct have managed to survive—including some previously unknown to the general public, such as the fluorescent pink Mount Kaputar slug. The fire crisis of 2020 has also fueled a renewed consciousness among many Australians that the “natural world,” and not only humans, can suffer injustices. “I am here for one billion animals that aren’t,” reads one protestor’s signboard.

But discourses of emergence, regeneration, and hope stemming from ashen worlds—the phoenix complex—are also risky. They may obscure the destructive forces that produce ashes in the first place. They may stifle efforts to transform the everyday forms of production, consumption, and representation that render the “natural world” meaningful only to the extent that it is useful to humans. As the sense of crisis wanes in the aftermath of forest death, so too does the interest of the public and media. Business as usual today becomes the latent promise of fires tomorrow. The unprecedented becomes the new normal. Easy conclusions help quell our consciences and consciousness. After all, it’ll grow back.

The ashen worlds of forest death bring us to reflect on the ambiguous temporality of crisis and crisis-writing. As I type this essay in the late months of 2020, the Bureau of Meteorology had declared a La Niña, signaling a wet spring and summer for northern and eastern Australia. But fires will almost certainly repeat and intensify under the heating and drying trends of climate change. Meanwhile, species like kangaroos and koalas, whose incinerated bodies once epitomized the tragedy of the fires in media coverage, have once again become the object of systemic culling. How do we remain response-able to omnicide while also acknowledging multispecies resurgence? How does one write crisis, in and beyond crisis as event and process? How can we turn the heat down on the planet, while also keeping issues hot? Staying with the trouble of ashes may help us avoid the violence of forgetting. At once living, dead, and non-dead, ashes are the pulverized remains of our many more-than-human companions. And so we must allow ashes to haunt us. They are silent witnesses. They are a call to action and life otherwise.