Losing Paradise: War Comes to a Biodiversity Hot Spot

From the Series: The Central African Republic (CAR) in a Hot Spot

From the Series: The Central African Republic (CAR) in a Hot Spot

Though the Central African Republic has witnessed a handful of coup d’états in its postcolonial history, the most recent one, in March 2013, is unlike those in the country’s past. Whereas other coups entailed a relatively quick transfer of power, this one has escalated into a civil war. And whereas other coups affected only certain parts of the country (primarily the capital and people along roads to Chad), the violence that followed this one has spread far into even formerly peaceful southwestern CAR, and even into that region’s Dzanga Sangha Reserve (RDS), a biodiversity hot spot. My perspective on this recent coup d’état and its aftermath is framed with a natural-resources perspective based upon my ethnographic research in the southern, forested region of CAR since 2002. My account documents how both people and wildlife living in remote protected areas fall victim to mounting sectarian violence and an enduring humanitarian crisis. Further, in this case, it demonstrates how areas peripheral to intense fighting, although seemingly stable compared to other areas, require peacekeeping and humanitarian efforts to maintain decades-long efforts at wildlife conservation and stabilize local livelihoods.

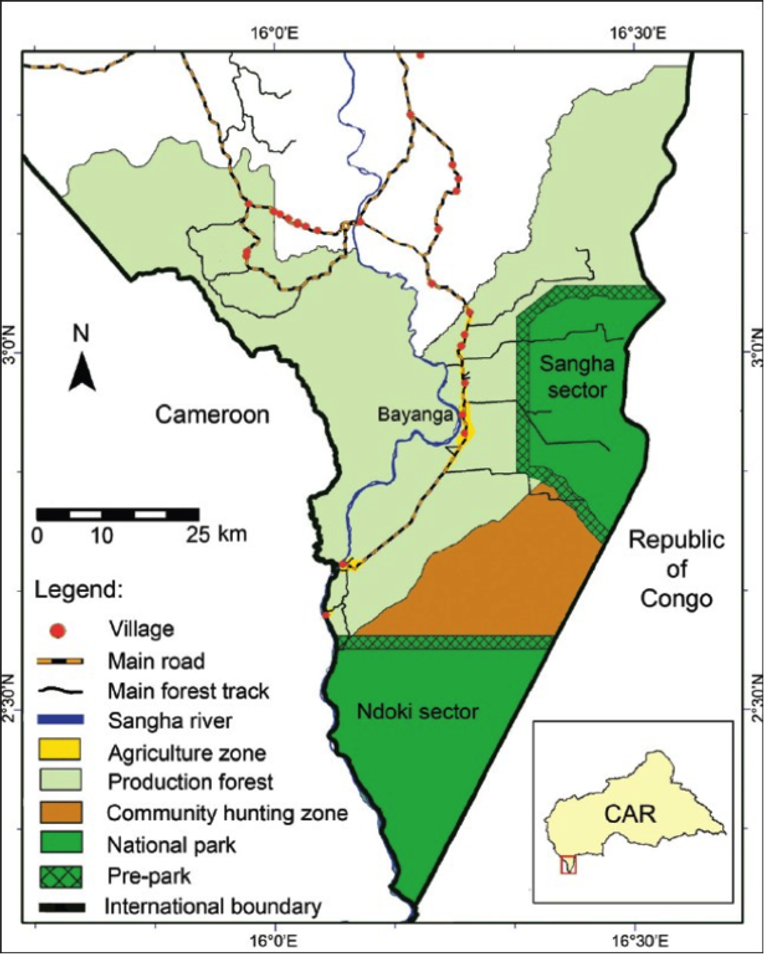

Overall, the RDS, with its particular geographic isolation, has been a place of relative security for humans and animals alike. It is one of the last strongholds of western lowland gorillas and forest elephants in the Congo Basin. The human population of the RDS is settled across seven villages, Bayanga being the largest. The primarily migrant population of the RDS contains ethnic groups from all regions of the CAR, as well as many other countries in the region and further afield. The fluctuating socioeconomic history of the RDS has created a complex web of negotiated natural-resource use and extraction regimes involving the local conservation project, a foreign-owned logging concession, and the reserve population. Conservation work has entailed tension with these other resource-use modes, but integrally protected wildlife species remain.

But all this has been changing as the area has—first gradually, and now rapidly—been affected by violent conflict. My earlier work in Bayanga with market women helped me to understand how border conflicts in other parts of the country can have indirect consequences over long distances. For instance, in 2008, conflicts in neighboring Chad that spilled over the northern borders of the CAR began to stall the flow of staple sources of income for market women, such as onions and peanuts. Wildlife has also seen increased hunting pressure as regional conflict resulted in more widespread access to guns.

During conflict, the natural resources of protected areas make them zones of economic opportunity. Like much of the rest of the country, over the past year the RDS fell victim to vandalization, looting, extortion of goods and money, and violence against civilians. In response, local inhabitants and politicians sought shelter deep in the forest. Conservation efforts stalled. At this time, bushmeat hunting rose as people looked toward the forest for both sustenance and income.

Amidst violence, chaos, and a lack of political control, Sudanese poachers posing as Seleka forces made a successful trek into the interior of the RDS. On May 6, 2013, seventeen poachers armed with Kalashnikovs went into one of the parks, to the well-known elephant sanctuary, Dzanga Bai. The poachers were successful, rapidly massacring at least twenty-six elephants. For a brief time, this uncommon and high level of violent human activity displaced elephants and other animals from this site. Such an extreme and singular event of elephant poaching also caught the attention of the international community, bringing together in May 2013 then-president of the CAR, Michel Djotodia, the Gabonese government, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and NGO personnel from World Conservation Society, and the World Wildlife Fund. The meeting resulted in intensive training and aid to the local military personnel and park guards charged with protecting the RDS.

Life continued in Bayanga and the RDS, while war escalated elsewhere in the country at the end of 2013. In late December, hunters from villages just beyond the northern border of the RDS descended into the forest to poach elephants. This time, luckily, only one elephant was killed. Park guards, working with a small band of Seleka forces in the region, apprehended and arrested the four poachers responsible, who included important civil servants. But feelings of insecurity rose.

In March 2014, anti-Balaka forces reached Bayanga. They recruited and vandalized Muslim businesses and homes, and those Muslims who hadn't already fled did so. In one instance, a handful of anti-Balaka incited the local population into vandalizing and looting goods from two Muslim-owned shops. The ease with which they incited people is chilling, as people in the area had not previously been involved in sectarian conflicts.

With continued social upheaval and political insecurity, the wealth-generating natural resources located in the RDS will continue to attract people seeking opportunity amidst chaos and insecurity. Under the direction of the local Conservator, park guards remain committed to the protection of wildlife through anti-poaching patrols. However, with international peacekeeping efforts absent from the RDS, it is likely that both humans and animals will continue to be met with violence and banditry as militias move throughout the country. For park guards working in the RDS, their work becomes tremendously more difficult when met with increased firepower. Without on-the-ground support and humanitarian aid, conservation efforts in this region will continue to face mounting challenges. For those of us who are physically removed from this crisis, yet intimately connected to the CAR, we struggle to find ways to help as violence between humans escalates and gets enacted upon animals, and a fragile paradise appears lost.

The author would like to thank Rod Cassidy and Louis Sarno for their invaluable assistance in the preparation of this essay.

1. Sandker, Marieke, Bruno Bokoto-de-Semboli, Philipp Roth, et al. 2011. "Logging or Conservation Concession: Exploring Conservation and Development Outcomes in Dzanga-Sangha, Central African Republic.” Conservation & Society 9, no. 4: 299–310.