Mapping Assertion and Belonging: Reflections on the Life of the Anti-CAA Movement in New Delhi, India

From the Series: Global Protest Movements in 2019: What Do They Teach Us?

From the Series: Global Protest Movements in 2019: What Do They Teach Us?

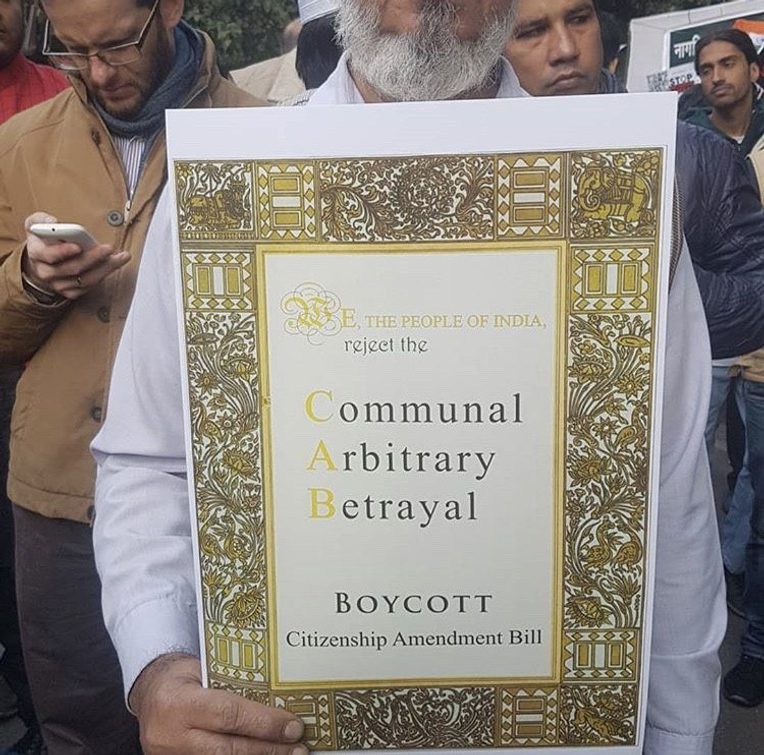

December 15, 2019, marked a horrific Sunday in the history of the Jamia Millia Islamia University in New Delhi. Just three days prior, the ruling Hindu nationalist Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) pushed through the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), granting citizenship to all persecuted religious minorities from the neighboring countries of Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan, while explicitly excluding Muslims. Additionally, the government proposed a nationwide citizenship verification process, or a National Register of Citizens (NRC), which made documentary evidence in the form of birth certificates and land deeds from the last fifty years a mandatory basis of citizenship. While non-Muslims lacking such evidence would find legal protection under the new citizenship legislation, Muslims in the same situation would be rendered stateless and stripped of their legal rights.

Protests quickly emerged to challenge this blatantly anti-Muslim and draconian act. Spaces like Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University (both historically known to represent Muslim minorities since the anti-colonial freedom movement)1 emerged as major centers of revolt. As students gathered for a peaceful protest at Jamia in particular, heavily armed police forces stormed in, sealed the campus with barricades, and brutally suppressed any attempts at resistance. Policemen fired rounds of smoke canisters and tear gas shells, brutally thrashed students, and damaged university property beyond repair. A fourth-year law student lost an eye. Someone’s arm was fractured. My own sibling had only recently graduated from Jamia and continued to frequent the area for professional and personal reasons. When I learned what was happening, my heart skipped a beat—what if my brother was one of those being harmed and sealed in the campus? I made frantic calls of panic to check his whereabouts. A few minutes later I heard he was safe, but only just before I learned others were not. Visuals of students hiding under library desks and bleeding while being thrashed and abused by the police started circulating on social media. As police continued to place Jamia under siege, civil society groups issued immediate calls to condemn the violence and demand a release of detained students. Everyone was asked to immediately gather at the police headquarters in central Delhi: “We cannot enter Jamia, roads are sealed. Come to Delhi police headquarters right now!” repeatedly flashed on my phone screen and it was the only resort to resistance one knew at that moment.

Prior to the announcement of the CAA, the ebbs and flows of dissertation fieldwork had kept me busy and occupied. I had spent the previous several Sunday evenings either preparing to resume my research or traveling from my parents’ home in Delhi back to my field site in the neighboring city of Gurgaon; however, this was no ordinary Sunday evening in my ethnographic everyday. My dissertation research focuses on land disputes and urban planning in the peripheries of the capital city of Delhi. At the time, I was studying how enduring histories of settlement, land entitlements, conflicts, and displacement shaped current practices of claim-making and belonging centered around land in a rapidly urbanizing landscape. I was exploring how people were disputing questions of rights and access to land in administrative spaces and their everyday lives alongside the aspirations and anxieties they were articulating about urban futures. In all of this, the question of who belongs and who became excluded from state visions, urban life, land, and law were critical concerns. In the events of this unprecedented Sunday evening in 2019, I found myself confronting the same questions yet again.

Responses to the CAA hinged on larger discourses of suffering and displacement and questions of belonging. This was not an unknown moment of discrimination toward Indian Muslims but rather marked a longer history of violence and denial integral to the constitutive power of the Indian state. In 1992, Hindu nationalists destroyed a famous mosque under the pretext that the religious site rested on the ruins of a Hindu temple, inciting riots all over the country. In 2002, a state-complicit genocide against Muslims swept through the western state of Gujarat, which at the time was administered by India’s current prime minister, Narendra Modi. As a Modi-led government came to power in 2014, hate crimes and lynching of Muslims have subsequently risen at a pace and to a scale that it no longer ceases to shock. Following Modi’s reelection for a second term in May 2019, his party suspended Article 370 of the Indian constitution, which grants special status to the only Muslim majority state of Kashmir. As if the trauma of several years of military occupation was not enough, land in Kashmir would now be made available to India’s larger non-Muslim majority, business corporations, real estate, and the grand project of “development.”

In the aftermath of these cascading anti-Muslim and state-led actions, the CAA arrived as a calamity that only marked continuities with the past instead of ruptures. The CAA arrived on the back of enduring histories of conflict and dispossession explored in my own fieldwork in other locales and experienced by other actors. For Indian Muslims, this continuous process of dispossession was both from land, property, and urban space as well as from a life of dignity, self-respect, political status, and eventually everything that constitutes a sense of being and belonging (Tambar 2016).

As an anthropologist studying people’s changing relationships with land, as well as an Indian Muslim, I was no neutral bystander to the growing fight against this ongoing project of displacement heightened by the CAA. Instead, I found myself immediately politically implicated in these struggles. Responding to calls for action against the attack on Jamia, I joined the rush to the Delhi police headquarters. Huge crowds of known and unknown faces had gathered to actively seek updates on Jamia and the detained students. “Were bullets really fired? Did someone die? For how long will the state crush student rebellions?” were some of the questions that swirled loudly and softly past me.

Many labeled the events at Jamia as part of a standard account of student suppression that the right-wing government had normalized in the past few years. Yet, the binary of fascist state forces versus student uprisings seemed limited in its ability to unravel this specific event. The intensity of police violence witnessed at Jamia could not be disentangled from the broader neighborhood surrounding the university. The localities of Jamia Nagar, Batla House, Noor Nagar, and Shaheen Bagh (the final epicenter of the protests) were known to every Delhi resident as “Muslim areas.” Working-class and middle-class Muslims, the primary targets of this citizenship legislation, are the dominant population of this region. They have lived segregated and ghettoized lives lacking basic civil amenities and with the complete apathy of the state for many years now. For almost all of them, Jamia allowed them visibility in the broader landscape of the city. Jamia was a landmark, a symbol of acknowledgment from the broader non-Muslim public and their primary source of upward mobility. An attack on this university was a clear attack on the community, their locality, and their spaces of belonging. And it was in response to this attack that a larger movement emerged in Delhi, one that stemmed both socially and spatially from the community and from historically ignored locations within the urban political geography. It was a movement that challenged both the specific assault on the community’s university, as well as the larger project of illegality or “non-belonging” that the state unleashed on them.

Ordinary Muslim residents, particularly women, united on the streets without any formal organization or political party support and decided to occupy a nearby highway and thus intentionally disrupting the everyday workings of the city. In the many days to follow, this highway and its surrounding neighborhood of Shaheen Bagh became the chief site of the anti-CAA battle in the city. Protests spread elsewhere in the country and by no means were Muslims its only architects. However, despite the spread of the movement far and wide, Shaheen Bagh emerged as the primary face of the movement in the country.

If in Hong Kong the spread of protests to “non-places” such as airports or shopping malls (see Huang’s post, this series) reconfigured the urban form with new meanings and produced novel relationships between citizens and the urban landscape, the opposite was true in the Indian case. Certainly, even in India, political activity that often seemed far removed from the rhythms and temporalities of daily life had also been “brought home” to the neighborhood through the anti-CAA movement. Yet the eventual centralization of protests in this very historically ignored Muslim “ghetto” revealed how the existing sociopolitical urban form and prior histories of organizing communities through space shaped the life of the movement in India. It was no ordinary coincidence that an already persecuted minority decided to challenge their further state-initiated persecution from their own historically segregated neighborhoods rather than elsewhere. The specific spatial and political location of the Muslim community within the urban form of Delhi shaped the practices and politics of belonging within the movement. It forged vocabularies of protest. It contributed to the internal dynamics and heterogeneities within the movement.

Zooming in on the Shaheen Bagh protest venue then, I situate such politics of belonging within the different mediums through which protestors registered their defiance. First and foremost, this included the conscious sites where the movement manifested and the spatial tactics of protests (such as sit-ins or highway blockages). Second, I pay attention to the multiple sociolinguistic modes of public address and assertion that ranged from a language of law and rights to one of dignity and pride in religious faith and identity.

By bringing to light these contrasting spatial, affective, and linguistic forms through which public presence was marked, I also then hope to reflect on the role of anthropology in comprehending the frictions, contradictions, openings, and closings within such movements. In line with the contributions in this series, I would like to argue that detailed ethnographic attention to the everyday life (Das 2006) of protests can contribute to keeping alive the irreducibility and complexity of these present moments as well as helping notice the aspirations, expectations, and possibilities these generate for a politics of the future.

* * *

“Yeh Sarzameen Allah ki Hai. Modi ji ki Nahi. Woh kyun humien Nikal Rahe hai [This land belongs to the Almighty and not to the Prime Minister Modi. Who is he to ask us to leave]?” exclaimed a middle-aged woman wearing a hijab in conversation with a TV news anchor at the Shaheen Bagh protest venue in late December. Another woman, standing adjacent to her quickly added: “Yeh sochne ki baat hai ki agar mein yeh Jhel rahi hoon toh meri aanewali Nasle Kya Jhelngi [It is worth thinking that if this is what I am facing then what will our future generations face]?”

These local women from Shaheen Bagh had gathered for their night-long sit-in at the protest venue that had over time seamlessly merged with their quotidian lifeworlds to produce new rituals, routines, and temporalities. “Roz sham ghar ke sab kaam karke or Maghrib ki Namaaz ke baad hum yaha aajate hai [Every evening after finishing all household work and after the evening Maghrib prayers we all come here],” was a common response to questions about how they were finding time to protest amid their home and work commitments.

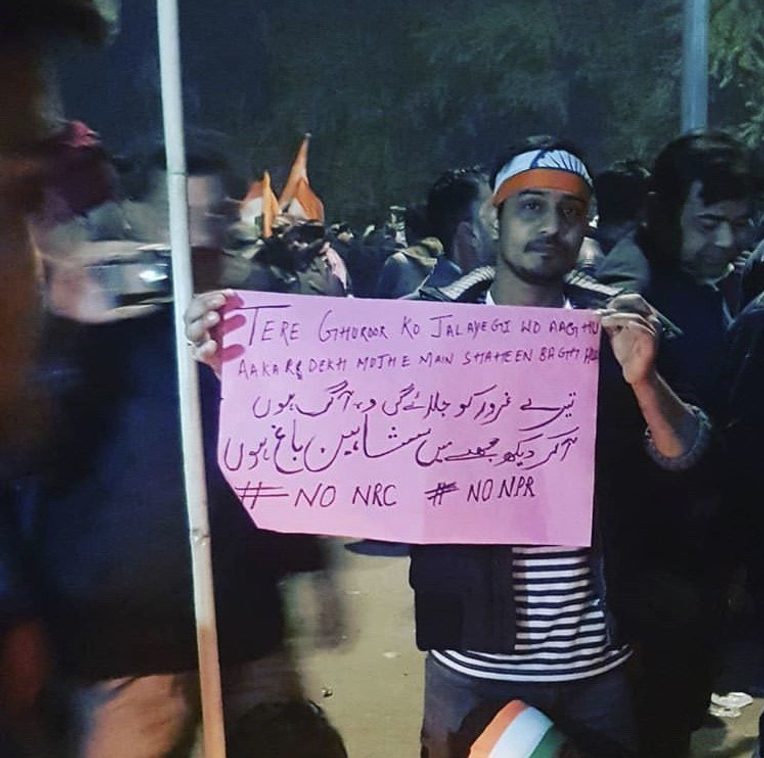

A movement that was spearheaded initially by these women had now gained momentum and had grown to a crowd of thousands from near and far. Muslims, non-Muslims, students, activists, artists, academics, and many others constantly flocked in and out of the protest venue. The entire area was covered in quotes, graffiti, and images of Gandhi, anti-caste leader B. R. Ambedkar, Maulana Azad, James Baldwin, and other anti-colonial leaders. The sounds of a fierce speech by a young protestor, asserting not to move an inch (Hum hatenge nahi yahan se) from the sit-in until the CAA was revoked, echoed in one corner. The noise quickly traveled to merge with softer sounds of poems and songs of revolution. Somewhere in the background, chants of Aazaadi, aazadi (freedom, or freedom from this fascist regime) could also be heard. Shaheen Bagh, once invisible, erased, or non-existent to the rest of the city, was now alive and visible with dissent and the demands for recognition and belonging.

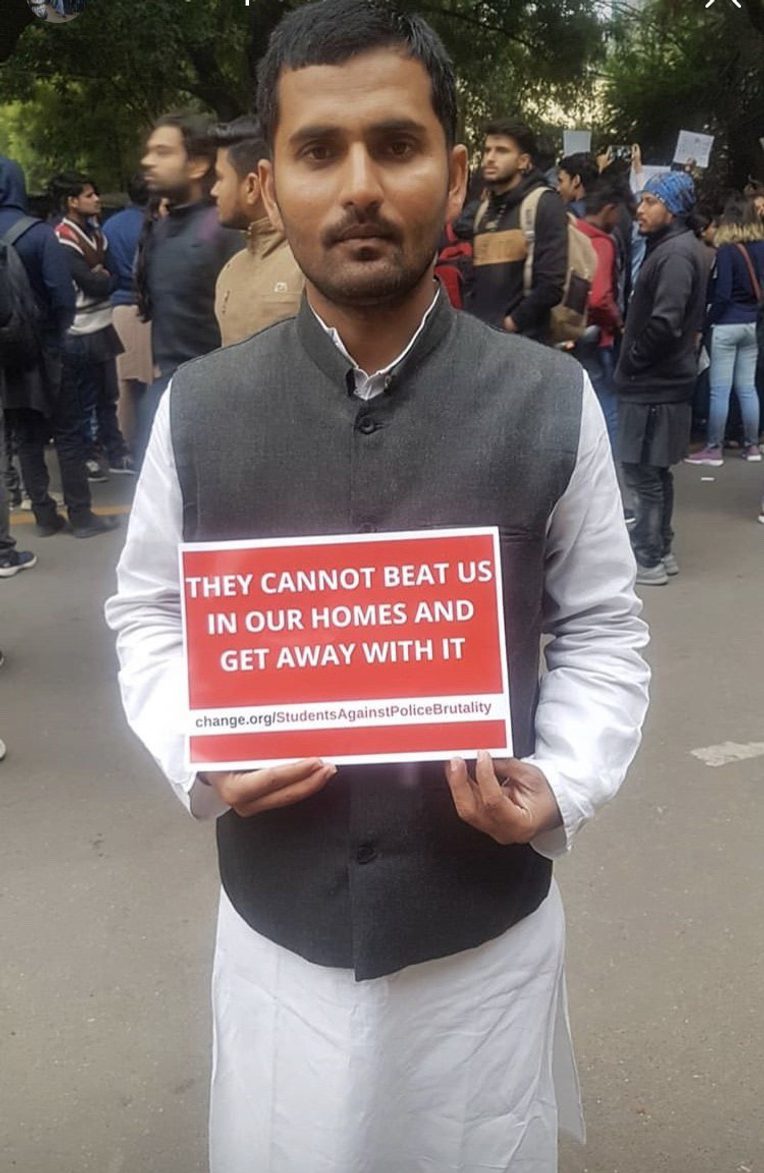

One of the ways this was particularly evident lay in the spatial tactics of protest adopted by the Shaheen Bagh residents. Highways were blocked, night and day long sit-ins became an everyday affair, and police barricades were transformed into actual sites of protest. The women of Shaheen Bagh were out in the streets all night, leading protests and defying standard tropes of the oppressed Muslim woman who lacked agency and needed saving (Mahmood 2011). Disrupting traffic and invading the regular flow of city life were attempts at place-making (Gupta and Ferguson 1997) that helped reassert being and belonging amid multiple scales: the neighborhood, the city, and the nation-state. For protestors, this was a crucial mode of marking public visibility, thus creating the potential for “being seen” and noticed by both fellow city residents and state actors.

In fact, the movement in no way stood entirely outside the ambit of the state or its so-called liberal framework. This was apparent in the language of claim-making and assertion adopted by many protestors, embedded in the vocabulary of rights, justice, and the constitution under the gaze of the state. “Yeh humara Haq hi. Humein Insaaf chahiye. Yeh kannon constitution ke khalif hai [This is our right! We want justice. This law is against the constitution],” were some of the common expressions one came across in this regard. “Itne din hogaye protest karte huye lekin Bjp ka koi neta yaha nahi aaya [It has been so many days since we are protesting but no BJP leaders have visited us here],” were additional concerns indicative of the desire among many protestors for the state to turn its attention toward them and their demands for revoking the CAA.

As mentioned already, this legislation held dangerous legal implications for Indian Muslims. It rested on redrawing binaries between pure authentic insiders that “deserved to belong to the nation” and impure outsiders or “infiltrators” (invariably Muslims) of whom the nation had to be sanitized. By suspending all legal protections and rights in relation to a sovereign power, the act intended to render Muslims illegal and contain them in what Giorgio Agamben (1998) calls “the state of exception.”

However, if the rule of law through this legislation acted to exert power and emerged as a tool of governmentality, then it clearly also provided avenues for resistance (Sundar 2011). As observed from the vocabularies of protestors described above, many deeply questioned the state from the same terrain of law that had threatened to render them lawless (Thompson 1975) by demanding Haq (rights) and insaaf (justice). They held the state accountable to its own legal promise of equality and secularism enshrined in the Indian constitution.

While the adoption of this language of the law resembled a demand for state recognition and constitutional inclusion, the uniqueness of the Shaheen Bagh protests lay in also demonstrating other vocabularies of staking belonging that rested outside the domain of the liberal state structure. If some showed faith in the formal institution of the law, many others were quick to point out the limits of the law and the inadequacies of legal guarantees of secularism in making room for a life of dignity and respect.

Unlike the functioning of secularism in other contexts, which often demands strict separations between state and religion, secularism in India on paper claims that the state will acknowledge all religions equally. Instead of erasing religion from the public domain, it claims that all religious practices can find equal space to coexist in public (Bhargava 2010). Yet since the moment independent India materialized and was partitioned, and as Muslims were reduced to the category of a minority, religious minorities have constantly been treated with suspicion and asked to prove their allegiance to the Indian state (Pandey 1999). Muslims have been expected to contain their religious selves, erase their religious differences, and assimilate with the non-Muslim majority (Asad 1993). The latter comprising both right-wing nationalists alongside liberals or leftists have all repeatedly sought from Muslims an active demonstration of their secular credentials. Any displays of religious faith, practice, and markers of observance have deemed Muslims extremists, jihadi, backward or “bad Muslims” in need of segregation from secular, progressive, and educated “good Muslims” (Mamdani 2002). In all of this, the unequal burden of secularism had rested on the shoulders of Indian Muslims for too long and many Muslims found within the anti-CAA movement a space to contest this asymmetry and release themselves of this burden.

As a result, the movement at Shaheen Bagh witnessed the rise of a new set of younger Muslim actors no longer afraid to assert their religious identity in public. They demanded “belonging” to the nation with dignity and respect and a life devoid of humiliation for their religious affiliations. In their speeches and addresses, they displayed pride in “being Muslim” and believed in leading this movement on their own terms and conditions. Insisting on calling the movement a “Muslim movement” and raising slogans of Intifada Inqilab (uprising or revolution) and Allah hu Akbar (Allah is Great), “new Muslims,” as sociologist Tanveer Fazal argues, are “no longer burdened by the guilt of Partition, or subdued by the politics of being a minority.” Their struggle is not merely restricted to a revocation of the citizenship act. Instead, from the platforms offered by the Shaheen Bagh protest, they highlight a longer history of systemic oppression and displacement.

If religious faith and difference had been the basis of the constant persecution of Indian Muslims, for these new Muslims, such religious difference also legitimately emerged as the basis of claims and contestations. Religious practice and identity also became key sites of negotiation through which the politics of belonging and non-belonging unfolded at Shaheen Bagh. However, as Talal Asad (2003) argues, religion is not antithetical to secularism, pluralism, or mutual care, nor can it be ignored as a tool of mobilization within the anti-CAA movement. Even those at Shaheen Bagh espousing the language of rights and justice were not opposed to religious faith and practice. The language of Haq (rights) and insaaf (justice) constantly interspersed with the language of Iman (faith) and Mazhab (religion), bringing together contrasting forms of claim-making that helped refashion identities and political subjectivities.

* * *

In the months that followed the initiation of the anti-CAA protest up until early March, Shaheen Bagh continued to stand firm even amid a state-sanctioned pogrom against Muslims in the northeastern parts of the capital city. Right-wing mobs from the city and its outskirts flooded working-class neighborhoods, lynching Muslims, damaging property, and decimating Muslim lives. The attempt in many ways was to warn the protestors of Shaheen Bagh to either call off the movement or meet a similar fate. Yet, the women of Shaheen Bagh refused to budge from their sit-ins, and peaceful protests continued. It was only with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the imposition of a country-wide lockdown that protestors were finally compelled to suspend the movement.

In its aftermath, activists and young Muslims involved in the protests are regularly arrested today under ambiguous legal charges of inciting violence or hate speech. On the other hand, muscle men of the ruling Hindu nationalist party, who pull out guns in public to intimidate protestors and are the real organizers of riots, continue to enjoy legal exemptions

In the current moment as the CAA and NRC continue to stand valid and as an air of uncertainty lingers over the future of both the Shaheen Bagh movement and Indian Muslims, how can anthropology help? Similarly, what conditions of possibility are produced for anthropological knowledge when such movements of resistance embrace ethnographers and ethnographic practice?

In the act of writing and reflecting on our experiences of such movements, both as participants and ethnographers, anthropologists not only help etch these struggles in the public domain but also hold together the conflicts and contradictions within these movements. Even in the context of Shaheen Bagh, where experiences of denial, violence, or precarity for Indian Muslims mapped onto claims of belonging that contested Muslim exclusions, a range of contrasting forms of claim-making emerged. Instead of looking for resolutions to such paradoxical forms of assertion and imposing order on the ambiguities they pose, anthropology allows us to think of them as carrying political potential and value (see also the conclusion of this series). Ethnographic engagement with these moments, no matter how unproductive and confusing they may appear, can help us broaden our understanding of the workings of power and amplify the voices of critique that emerge in response. Likewise, such engagements can help illuminate the range of possibilities (both political and affective) such paradoxes produce for resistance movements in the future.

1. JMI was founded in 1920 and AMU was founded in 1875. Other than being Muslim institutions of reform and modern education, they were also crucial to the Indian freedom struggle. They were important sites of nationalist political thought and activity.

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Asad, Talal. 1993. Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

–––. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Bhargava, Rajeev. 2010. The Promise of India's Secular Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Das, Veena. 2006. Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gupta, Akhil, and James Ferguson, eds. 1997. Culture, Power, Place: Explorations in Critical Anthropology. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Mamdani, Mehmood. 2002. “Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: A Political Perspective on Culture and Terrorism.” American Anthropologist 104, no. 3: 766–75.

Mahmood, Saba. 2011. Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Pandey, Gyanendra. 1999. “Can a Muslim Be an Indian?” Comparative Studies in Society and History 41, no. 4: 608–29.

Sundar, Nandini. 2011. “The Rule of Law and Citizenship in Central India: Post-colonial Dilemmas.” Citizenship Studies 15, no. 3/4: 419–32.

Tambar, Kabir. 2016. “Brotherhood in Dispossession: State Violence and the Ethics of Expectation in Turkey.” Cultural Anthropology 31, no. 1: 30–55.

Thompson, E. P. 1975. Whigs and Hunters: The Origins of the Black Act. New York: Pantheon Books.