On The People’s Circle for Palestine at the University of Toronto

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

As three non-Palestinians—one graduate student and two faculty members at the University of Toronto (UofT)—we reflect on the People’s Circle for Palestine and what it means to be “for Palestine.” Using different communicative styles and mediums, we share stories of how the UofT encampment, one of the largest student encampments for Palestine in North America, demonstrated what solidarity looks like as it became an embodiment of co-existence, unlearning, refusal, and anti-colonial resistance.

On April 1, Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza was broadcasted on our screens, and UofT had been ignoring student demands for disclosure and divestment for months. Left with few options, students occupied the President’s office to force a meeting with him. When they finally met, UofT President Meric Gertler claimed not to know about the scholasticide going on in Gaza (at the time, all of Gaza’s twelve universities had been destroyed). He told students that there was a “diversity of opinion” on the issue.

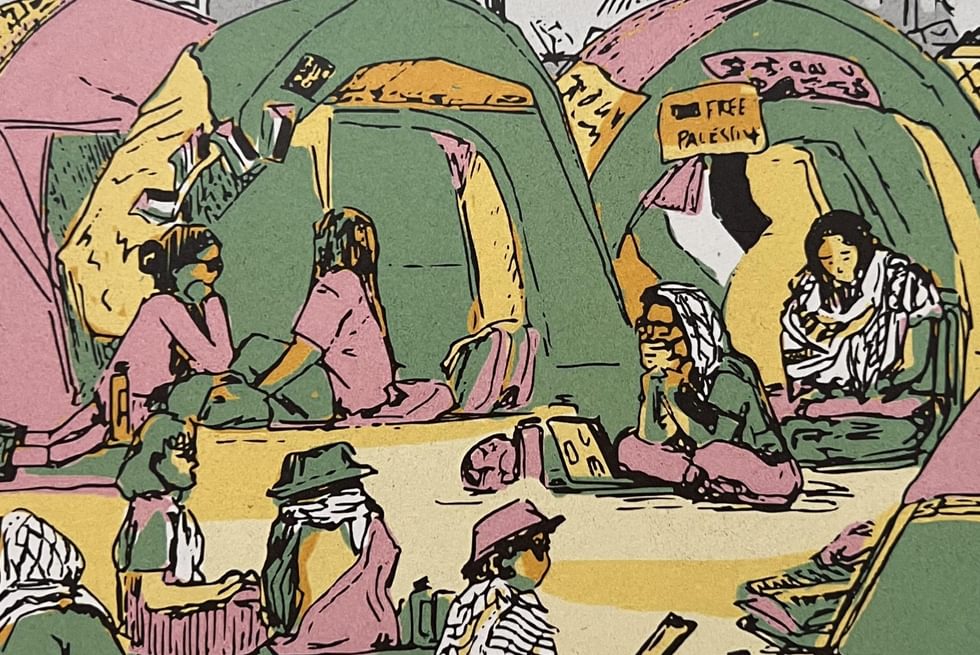

On May 2, over 60 students set up a protest encampment on the grass of UofT’s Front Campus, which they called The People’s Circle for Palestine. For sixty-two days the OccupyUofT encampment challenged the university administration and their strategies of misinformation. Tirelessly responding on social media, and through press conferences, community events, and teach-ins, student organizers spoke back to the university’s lies, including the increasing violence from white supremacist, pro-settler-colonial groups.

As for the UofT’s higher administration, it reacted to the encampment by turning “facts”—there is a genocide in Gaza; UofT has investments in companies that profit from apartheid, war, and illegal occupation, the encampment was peaceful and inclusive—into “opinions.”

What happens, as Hannah Arendt argued in her 1967 essay “Truth and Politics,” when “factual truth” becomes a matter of opinion?

To this day, UofT President Gertler has yet to meet with the People’s Circle for Palestine negotiating team. As for the UofT emissaries he sent, they refused to meet the three demands of student protestors: disclosure, divestment, and the severing of ties with Israeli institutions established on illegally occupied Palestinian land. Instead, as the camp was in full swing, UofT hired a large team of lawyers to defame and dismantle the student encampment. UofT claimed “irreparable harm” had been done, accused the peaceful, multi-faith encampment of being “violent” and “antisemitic,” and sought an injunction to allow police to forcibly remove them. UofT’s public branding of “care” for students, and its DEI slogans, became an ironic performance that clearly contradicted these claims.

If inconsistencies between university branding and managerial practices manifest as irony, UofT’s response was unsurprisingly consistent with the university’s ongoing commitment to the “ties that bind” and to the political influence of Zionist donors. It was also in step with the rising anti-Palestinian racism and repeated attacks by Zionist groups on pro-Palestinian protests on Canadian campuses. More broadly, UofT’s dealing with the OccupyUofT students was consistent with the values of a settler-colonial university. Indeed, the St George campus, where the People’s Circle for Palestine stood, is built on Indigenous land that was expropriated through an “educational land grant” bestowed by the British Crown. In line with British colonial legal praxis, UofT’s high administrators and lawyers used property laws to build a legal case against students.

The People’s Circle for Palestine not only demonstrated connections to other student movements on campus; it connected students to the horrors of what is happening in Palestine, to UofT’s complicity in these crimes, and to an embodied habitus of intersectional solidarity.

At the encampment, words seemed to have a life of their own, flowing out from the tip of my pen onto the paper and forming themselves into poems. Perhaps the words were taking inspiration from how the bodies of people connected physically and spiritually through prayer and music to form new landscapes of poetics and politics of solidarity and resistance.

More recently, standing alone, in front of the blackboard, the words seem too shy and afraid to come out. Or perhaps, just like me, they are still too shocked from being welcomed by the political hot tea first thing in the morning: “Did you hear? They killed him!” Ismail Haniyeh is dead, assassinated last night in Tehran. The plan for the day suddenly changed; now, I have to teach a class about what has just happened and what has been happening over and over again for almost eight decades. Politics is often like that; it comes in like a storm without warning, leaving a ruin in its wake.

While at the encampment, we had to deal with storms and their aftermaths. Rainstorms would leave the camp a mess, everything wet and often dislocated. Protesting UofT’s complicity in the ongoing genocide through an encampment meant that acts of protest were now extended to cleaning, rebuilding, and drying our tarps in the sun. Sometimes, it was people who would storm the encampment: the Zionists accompanied by white supremacists, Indo-nationalists, or Iranian monarchists. In this case too, bodies would also come together, this time to sing, chant and build a human wall to guard the encampment.

The encampment can be characterized by this coming together after a storm. Alone, with dozens of eyes staring at us in judgment, we were voiceless. The shock and suffering suffocating the words in our throats. It was when we came together that we could finally let the words flow into chants, prayers, and songs and channel the suffering into streams of tears that fell on our faces. The encampment was about protesting the repulsive way the dignity and life of Palestinians was discarded, but it was also about creating a safe space where we could mourn what was lost and come together to rebuild a different, brighter future from the fragments of the ruin the storm left behind.

In coming together there is a meaning that goes beyond each individual person; the same way the meaning of a poem conveys something beyond the single words that are linked together in a verse. Sometimes at the encampment I joined in the line of physical resistance at the gates. Other times, I was part of the line at Friday prayer. At times, I was a joyful extension of the Palestinian dance circle, Dabkeh, and then there were times that I silently observed the Hamotzi prayer, connected to my Jewish allies through the act of sharing bread. Every time, I embodied something of the people next to me, I embodied the meaning that exists in our coming together.

Through the encampment, I hold a bit of Palestine within me; as I sing Mawtini (My Homeland, a Palestinian anthem) after every morning meeting. Through the encampment, I also bring Palestine closer, and see its connections to issues of racism, discrimination, and police brutality within my university, an issue that can no longer be dismissed with a simple “take extra care in how you interact with your colleagues.”

In the judging eyes that stare at me when I talk about Palestine, there is always the same silent question: “But you are not Palestinian, so why?” And it is true—I’m not Palestinian, but I’m a UofT student and through the encampment, I carry a bit of Palestine with me. Just as UofT has an embodied memory of resistance on the Land it has stolen from the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and the Mississaugas of the Credit. Perhaps, the encampment is just the first verse in the poem of decolonization and freedom.

What follows is a photographic essay. I am a historian and, as such, I am drawn to the potency of traces, texts and things humans leave behind. As the People’s Circle for Palestine was birthed, as it grew and as it was eventually dismantled, the outer part of the fence that surrounded it was turned into a living and breathing canvas on which a wide array of expressions of solidarity, activism, and decolonial care were attached. Every day I would walk or bike by, I would see new banners, new drawings, paintings, photographs, stickers and graffiti. I documented the life of the canvas-fence until the last day of the camp. It now lives on as a photographic archive, which complements the material archive created by the student leaders, who carefully archived the larger items during the dismantlement of the camp.

These posters, banners, and artwork, most of which were handmade by students, but also at times by faculty, artists, and community members (including children), highlight the intersectional potency of solidarity. Through them, the voices of those the university strives so hard to simultaneously extract from (be it through labour or through student fees) and, when it comes to demands for disclosure, divestment and the cutting of ties, silence are seen, and heard.

June 2, 2024: A woman draped in an Israeli flag walked past the entrance of the People’s Circle for Palestine. As she did so, she smirked at student protestors and said: “I hope you guys never need health care from UofT, that’s all I can say.” The woman turned out to be a medical doctor and a faculty. After a video of the incident went viral, she issued an apology to her colleagues and coworkers (but not to the students). She acknowledged that what she said, “was wrong” but that her “words do not consciously reflect any prejudices.” Her response embodies the violent irony of the inherent double standards of UofT’s administrative class. This irony cannot create new solidarities. It can only recreate existing settler-colonial violence.

July 2, 2024: The Ontario Superior Court of Justice declared the camp peaceful and found no evidence of antisemitism, hate speech, or violence from student protestors. While the injunction was granted on the claim the encampment prevented others from using it as a “recreational space” (for, a UofT lawyer put it, “What if you just want to have breakfast on the front campus?”), it also revealed the extent of the university’s lies, and exposed the “banal evil” demonstrated by its ruling class.

OccupyUofT dismantled the encampment and left peacefully on July 3, but their movement for disclosure, divestment, and cutting ties from Israeli institutions complicit in genocide, continues.

Rather than allowing the administrative opinion to be taken at face value, student protestors, be it at UofT or elsewhere, educate us on what “never again" truly means. They demonstrate the irony of institutional messaging and remind administrators that it is an obligation for the university to comply with international law and immoral for it to be complicit in apartheid and genocide. By doing so, they counter the university’s attempts to misrepresent the facts with curated messages sent to the “university community.” In comparison to UofT’s disembodied performances of decolonization and DEI, the People’s Circle for Palestine demonstrated how to truly embody moral courage, inclusiveness, and decoloniality.