Pathways to Elite Insecurity

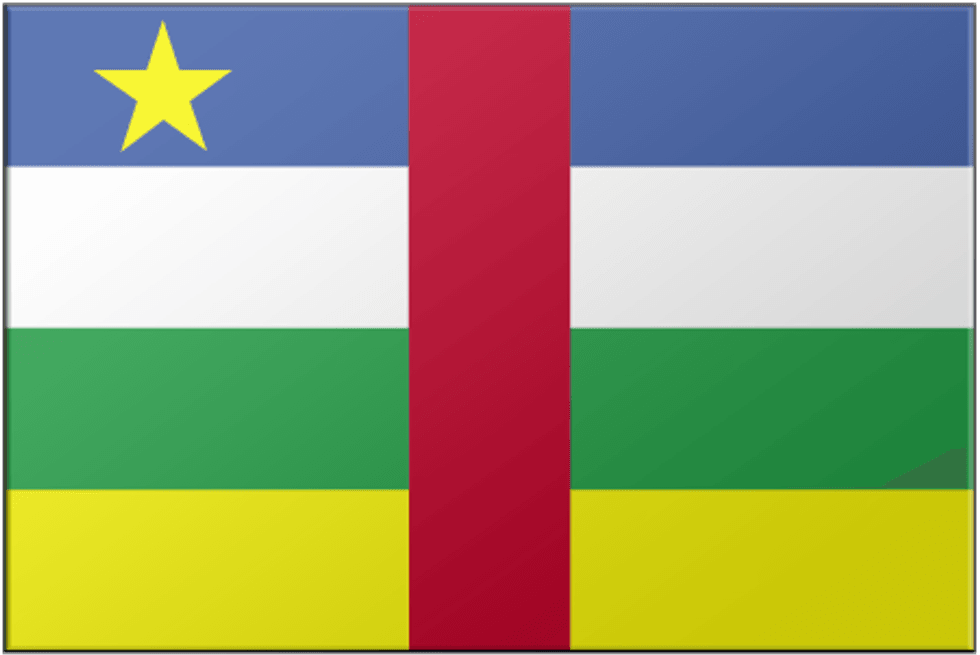

From the Series: The Central African Republic (CAR) in a Hot Spot

From the Series: The Central African Republic (CAR) in a Hot Spot

Atrocities between neighbours, Christians against Muslims: Central African Republic (CAR) today looks like a perfect illustration of the famous Latin adage “homo homini lupus est.” But the situation today must be understood in relation to the long history of intra-elite fighting and assassinations that ran in parallel to the more general distrust in society. Elites are of course fully part of the population, and family and friends of elites quickly became involved as further targets when elites were pursued or physically attacked and also as avengers. This piece sheds some light on the trajectories of elite insecurity, including elite behaviour, deficient state security, and outside support. This is not an exhaustive account—many more instances could be cited.

CAR has a small population and a small political elite—a rough guess would be around five hundred people. Virtually all know each other. This has not led to more trust. CAR elites have good reasons to be nervous about their security. A high number of assassinations and attacks on politicians and their homes and families have been reported over the last decades. CAR experienced one of the earliest coups in independent Africa (December 31, 1965). The erratic rule of “Emperor” Bokassa (1966–1979) included several unpredictable and sometimes-brutal assassinations, mostly of military elites.

Gen. André Kolingba (1981–1993) used arbitrary detention to cow his opponents, though he mostly refrained from political assassinations, despite facing a coup attempt masterminded by two later Presidents of the Republic (Ange-Felix Patassé and François Bozizé) in 1982. Kolingba used ethnicity as the basis for establishing whom he could trust, packing the army with his fellow Yakoma.

With the popularly elected President Patassé (1993–2003), things got worse again. The second mutiny of a sizeable part of the country’s army in 1996 provided the pretext for the assassination of former defense minister Christophe Grelombe. Grelombe was not the best-loved man in the country, as he was held responsible for some of the worst human rights abuses under Kolingba. But he was murdered together with his son, which made it look like a deliberate attempt to wipe out an entire political family. When former Prime Minister Jean-Luc Mandaba died in a French hospital and his son Hervé passed away shortly thereafter, many Central Africans interpreted these deaths as assassinations by poison, although the details of the deaths never became clear. Not only politicians were targeted: in 1999 the influential trade union leader Sonny Cole was shot at, arrested by the Presidential Guard, and beaten.

During the failed coup attempt against Patassé in May 2001, a handful of key personnel of the regime were killed, among them General Abel Abrou, Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces and the head of the gendarmerie, General Njadder Bedaya. In the following retaliation phase a bigger number of elite members were killed by death squads, including the Member of Parliament Théophile Touba and a member of the constitutional court, Sylvestre Omisse, the latter apparently because he had a name sounding Yakoma (although he was not actually Yakoma). In the period that followed the uprising, retaliatory acts targeted all affiliated with Kolingba. This included his friends and family, members of his political party, and the Yakoma in general.

Patassé’s downfall came when his formerly long-standing ally and former chief of staff Bozizé (who Patassé had chased from his position in late 2001 when he suspected him of plotting a coup) succeeded in taking the capital, Bangui, in March 2003. Under Bozizé as well, several acts of violence against elites were recorded. Ex-Prime Minister Koyambounou was reportedly beaten and threatened with a gun by Francis Bozizé, a son of the President. Koyambounou was later arrested under corruption charges. Another serious incident took place on March 22, 2005, shortly before presidential elections, near André Kolingba’s residence. Gunshots were exchanged between the security guards of the former President and unknown elements. The government later declared that soldiers on duty along the Ubangi River had accidentally shot and that no attempt on the life of Kolingba, a candidate in the elections, was made. Evidently, the interpretation was different on the side of Bozizé’s opponents.

Also under Bozizé, the fate of Charles Massi, a politico-military entrepreneur, made headlines. His family alleged that he had died in custody in January 2010 as a result of torture after having been handed over by Chadian forces to the CAR authorities in late December 2009. Massi had been a minister under both Patassé and Bozizé. He had run as a presidential candidate in the 2005 elections and, in 2009, assumed political leadership of a rebel movement. Massi was a controversial figure who straddled the civilian and armed opposition. His presumed assassination sent shockwaves through the entire political class.

Patassé might have had reason not to trust the army after three mutinies in 1996/97, but he made little effort to reform it. Instead he relied on his Presidential Guard, which in turn became much feared by his political rivals and civil society organizations. According to the official report, when the head of the MINURCA peacekeeping mission asked for restraint of the Presidential Guard, Patassé replied that it was the only force he could still count on and so he could not reform it. Under Bozizé the name of the Presidential Guard changed, but its members retained their brutal reputation. They were allegedly responsible for the worst human rights abuses in the provinces.

CAR was long linked to France by a partly secret defense agreement. While in other countries this could be seen as a kind of life insurance for the president and his inner circle, it was more ambiguous in the case of CAR; the balance sheet of French involvement shows is that there is no guarantee for those in power that they will be protected simply because there is a defense agreement.

Bozizé thus looked elsewhere for his own personal security. In the early days after his takeover he appealed to Déby to send a number of elite troops (allegedly about 150). South African specialists later were brought in during 2007 to train Bozizé’s Presidential Guard. In the end, it was the South Africans who desperately fought the Seleka rebels and suffered heavy casualties in early 2013.

Peacekeeping troops were not a reliable elite-protecting force either. A limited UN mission in CAR in the late 1990s (1,350 maximum authorised strength) had an equally limited mandate that was only extended to cover electoral assistance (legislative and presidential elections in 1998–1999). Though the 380-men strong sub-regional peacekeeping force established in December 2002 (Force Multinationale en Centrafrique, FOMUC) had as one of its original tasks to guarantee the security of President Patassé, it could not prevent the successful conquest of Bangui by Bozizé’s men in March 2003. The subregional peacekeepers failed again to stop the march on Bangui during the 2013 military takeover.

To summarize: CAR elites have learned to distrust each other, the national security forces, and also outside protectors like France, Chad, and international peacekeepers. They in fact face deadly threats, more or less constantly. Intra-elite distrust at least complements, but at times also exacerbates, the more generalised societal distrust in CAR.