Remote or Unreachable? The Gender of Connectivity and the Challenges of Pandemic Fieldwork across the Bay of Bengal

From the Series: A Collaboratory of Indian Ocean Ethnographies

From the Series: A Collaboratory of Indian Ocean Ethnographies

Episode 1 – An interlocutor called us from one harisabha, a weekly ritual gathering, of the Matua community in Bangladesh. He let us speak to one of the women over the phone who was also present at the harisabha. But the conversation was far from private: we heard the male participants by her side saying, “Switch to phone speaker! Talk on speakers!” When we asked her questions, men around her instructed her how to answer. Perhaps, they assumed she could not answer the questions correctly, she could give undesirable answers, or simply that she could not express her opinion without the cooperation of men.

Episode 2 – We asked one of our male participants if his wife would be available to speak to us over the phone. He insisted that the two of them should be interviewed together, even though we requested an interview with his wife alone. He asked us for the questionnaire and suggested that his wife would write back with responses. When we requested a call with his wife, he reasoned that his words would be enough.

Episode 3 – While speaking to a respondent’s mother on his phone, when we asked her which number we could use to call her, we heard her son in the background, “Obviously on my number!” She repeated his words.

The discourse on remote ethnography as a pandemic modality of research often underestimates power dynamics in the access to and use of technologies, and therefore the privilege of connectivity. In this essay, we reflect on the gendered dilemmas of doing online ethnography and phone interviews with members of the displaced, low-caste Matua religious community (see Lorea 2020b) located around the Bay of Bengal, particularly in West Bengal (India), Bangladesh, and the Andaman Islands. As part of a project on religious responses to Covid-19 and ritual innovations in Asia (see our blog CoronAsur), we were keen to understand how marginalized practitioners faced the challenges of lockdowns and responded to health guidelines that contradict their epistemology of healing. What emerged from our experience may provide ways to attune pandemic methodologies with the contextual intersections of gender, media, and power in the Global South.

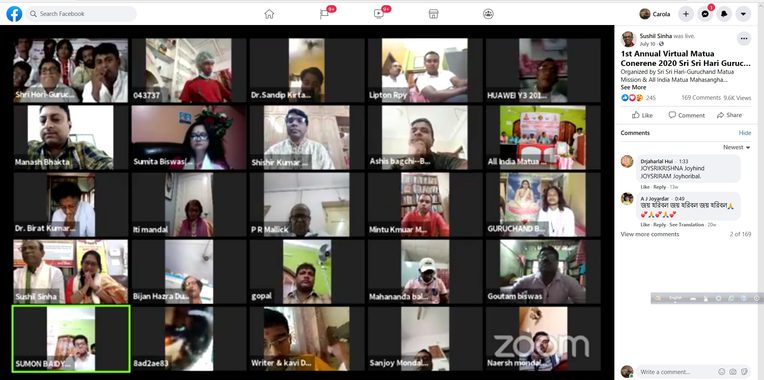

Like most religious communities during Covid times, the Matua usage of digital platforms (Facebook groups, YouTube channels, and Zoom calls) to recreate rituals and social gatherings in the cyberscape, skyrocketed in March 2020. But while the traditional festivals of the Matua community offer ample space to exhibit Matua women’s religious agency and authority in ritual performance (Image 1), these newly employed online platforms are overwhelmingly male dominated (Image 2). Livestreaming of sermons and speeches abound, but among hundreds of men’s voices, we were able to find only two women who had been invited.

Matua writers, mostly male, have defined their community as anti-patriarchal and feminist. Many Matuas believe that their gurus came on earth to endow women with dignity, while previous godly avataras failed to do so (Lorea 2020a). However, on these new digital venues of Matua religiosity, women (when present at all) are seen singing sacred songs or performing rituals from their homes, which are filmed and uploaded by man-handled technologies (Image 3). Their voices are reproduced, played, and listened to; but they remain unheard. While they are (over)seen from the boundaries of their homes, women participants told us that they listened to these newly mediatized Matua male voices, often from their brothers or husbands’ Facebook profiles, since they rarely had one of their own.

We postulate that digital ethnography relies upon media that inherently privileges a male-podium-speech in the way their sensory onto-epistemology works. In contexts where women are not socially enabled to express their voice through individual, articulated, assertive speech, online ethnography—just like logocentric interviews (see Jackson 2012)—can only be a participant listening to men's opinions. Technologies of communication like Zoom are ocular-centric and acoustically facilitate hierarchical and unidirectional speech. As scholars of sensory anthropology have demonstrated, androcentrism is embedded in most ocular-centric epistemologies (Devorah 2017). Thus, when religions shift to Zoom and social media platforms, this reconfiguration reinforces inequalities along patriarchal lines. Individual male voices come to the forefront. Videos of female participants portray women as emotional, melismatic singers to be seen, while male members are rational, articulated speakers over-seeing them.

This stands in opposition to lived practices in pre-Covid times. For the planning and the performance of rituals, especially big annual events and pilgrimages, Matua women travel far away from domestic duties to join religious festivals and participate with more ritual agency and authority. Their absence from homemaking labor is legitimized by the ritual exercise of devotion. This can be read in conjunction with female ethnographers' experiences of doing traditional fieldwork away from home, and the possibility of taking off from other roles. Just like our female interlocutors, we would normally take advantage of the ritual liminality of fieldwork periods (Kaeppler 1999) to take justified leave from ordinary domestic roles and from gender-biased care-giving roles both at home and in the workplace (Ferrant et al. 2014). These occasions of pause and exemption from domestic duties and household fatigue have come to a halt due to Covid-induced restrictions and the suppression of the most important Matua ritual gatherings.

Matua women in our remote field-work notes rarely have a telecommunicated voice, and even more rarely do they come with their full names. Our transcriptions are punctuated by references to Boudis (a kin-name for a married woman) without a personal name. They care for children, elders, homes, and fields, while our male interlocutors deploy the privilege of leisure and connectivity to engage in conversations with us. In our remote inter-views only a few members of the household appear visible and audible.

We could briefly talk with one of Carola’s fieldwork contacts, who is a primary school teacher in Orakandi (Bangladesh). She appears in our transcripts simply as Boudi, or wife (of the main interlocutor). With schools shutting down because of the Covid-19 pandemic, she started homeschooling her three daughters and giving online classes to her students. But most of her students did not have access to a smart phone with internet connection, as their families only owned one old generation cell phone (which they call “little phone”). Boudi called her students on the little phones on alternate days and helped them go through their lessons, but she worried that children from poor families will drop out (this is documented in Guru et al.’s essay on schooling in the southern regions of West Bengal in this series). She said that this is her way of showing devotion according to the Matua faith, whose main teaching is to love humanity (manushke bhalobasha).

Her worries were not unfounded. Since the beginning of our research in September 2020, we heard of at least seven school girls who got married, and one who committed suicide, in a Matua-dominant village in Bangladesh. With schools closed, young girls were suspected of idling away their time with (suspiciously non-Hindu) boys. Another side effect of the coronavirus is the viral spread of the “Love Jihad” rhetoric (Venkataramakrishnan 2020)—the politically motivated Hindutva-driven conspiracy theory whereby Hindu girls are unwillingly seduced and married by their Muslim lovers for the sake of conversion. Hindu parents and community leaders in several parts of India and Bangladesh are hardening young women’s restrictions from using phones and social media to safeguard the communalist honor by monitoring their interactions. Arranged marriages of underage girls are only one response to such anxieties. Another effect has been the increase in domestic violence. When young women are found spending time on the phone with unknown interlocutors, their safety is at risk. Keeping this in mind, we had to divide our interactions along gender and communal lines—for example, male Muslim researchers in our team could not talk alone on the phone with (Hindu Dalit) women interlocutors in order to protect their safety, and vice versa. In general, we could not keep women interlocutors on the phone for longer conversations, except for elderly widows.

One of our interlocutors, Ashalata, is an elderly woman in North 24 Parganas (West Bengal, India), who does not own a personal contact number. We needed to call one of her younger male family members in order to speak with her. Elderly women find it hard to hear and engage in phone conversations due to old age and lack of familiarity with the technology. Fieldwork in pre-Covid times allowed us to sit for hours in the kitchen with women, old and young, peeling potatoes and chopping vegetables while hearing their unfiltered and non-interpolated opinions. We would use immersive and multisensory (not merely ‘observing’) participation to understand their worldview in a “feelingful way” (Feld 1990 [1982], 237): not solely through logocentric utterances, but also through emotionally charged gestures and nonverbal communication which are often fruitful dimensions of ethnographic exchange with women (in contexts where their gender and culture does not encourage them to speak argumentatively for themselves) and elderly respondents (Jackson 2012).

While methodologically discussing phone interviews, Global North researchers often do not take into account the digital and technological divide exacerbated by gender inequalities (Burke and Miller 2001). In South Asian rural areas, a phone is often a commodity shared with the whole household (Mani and Barooah 2020), dwelling in the pockets of a man. While we easily reach young, able-bodied working males, their mediation is needed to reach women and elders.

All these issues inevitably influence our data collection and the ways in which we might challenge or reinforce gender hierarchies as we select and reiterate Matua voices through our ethnography across the shores of the Indian Ocean. Digital technologies are not neutral tools for academic inquiry with displaced communities around the Bay of Bengal—they are embedded in the politics of place, gender, and power and influence of ethnographic practice. In our research, we realized that existing power relations that forged gender inequalities were reproduced by new technologies of communication. In addition to the fields of socioeconomic disparity and class-caste divide, we witnessed how the pandemic has also exacerbated the display of politics inherent in the gendered access and use of communication technologies, such as access to mobile phones and individual ownership of a social media profile.

Burke, Lisa A., and Monica K. Miller. 2001. “Phone Interviewing as a Means of Data Collection: Lessons Learned and Practical Recommendations.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 2, no. 2: 1-8.

Devorah, Rachel. 2017. “Ocularcentrism, Androcentrism.” Parallax 23, no. 3: 305-315.

Feld, Steven. 1990 [1982]. Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics and Song in Kaluli Expression. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Ferrant, Gaëlle, Luca Maria Pesando, and Keiko Nowacka. 2014. "Unpaid Care Work: The Missing Link in the Analysis of Gender Gaps in Labour Outcomes." Boulogne Billancourt: OECD Development Center.

Jackson, Cecile. 2012. "Speech, Gender and Power: Beyond Testimony." Development and Change 43, no. 5: 999-1023.

Kaeppler, Adrienne L. 1999. “The Mystique of Fieldwork.” In Dance in the Field: Theories, Methods and Issues in Dance Ethnography, edited by Theresa J. Buckland, 13-25. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lorea, Carola Erika. 2020a. “Contesting Multiple Borders: Bricolage Thinking and Matua Narratives on the Andaman Islands.” Southeast Asian Studies 9, no. 2: 231–276.

———. 2020b. “Religion, Caste, and Displacement: The Matua Community.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. February 28, 2020.

Mani, Subha, and Barooah Bidisha. 2020. “Phone Surveys in Developing Countries Need an Abundance of Caution.” International Initiative for Impact Valuation. April 9, 2020.

Venkataramakrishnan, Rohan. 2020. “ ‘Love Jihad’: As Pandemic Rages, BJP States Turn Focus to Laws Based on Hindutva Conspiracy Theory.” Scroll.in. November 21, 2020.