Ressentiment, War, and the Anthropologist’s Silence

From the Series: Russia’s War in Ukraine, Continued

From the Series: Russia’s War in Ukraine, Continued

These days, even when social anthropologists leave—in a geographical sense—the place where they are doing field research, they often remain there: in private WhatsApp groups, Telegram chats, and so on. Researchers continue to follow the lives of the society they study, even without active involvement in discussing the issues that are important to one group or another. My research explores the interaction between religion, ethnic identity, and nationalism in one of Russia’s southern regions. I am also a member of several groups whose members exchange news, share recordings of sermons, make arrangements to participate in public events, agree to pray for a certain thing at a certain time, and so on.

On the evening of February 23, I was looking through chat logs, searching for material for an article I was writing at the time. The article was supposed to be about how various religious (or semireligious) communities reacted to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2022. I was collecting material on three groups who had offered up sustained protests against quarantine measures and demonstrated lasting dissatisfaction with the reigning political and ideological system. One group consisted of Russian Orthodox faithful, who were not associated with radical politics but who were pretty conservative (monarchism, Russian messianism, “traditional family values”). This was a WhatsApp group of seventy people. The second group had consolidated around ethnic religious revivalism in a republic in the North Caucasus (a Telegram channel with 20,000 subscribers). The third, and most diverse group, was a segment of the “Citizens of the USSR” movement, which insists that, legally speaking, the Soviet Union still exists, and every one of its citizens has the right to enormous riches and practically unlimited political resources. This group formed around a charismatic leader, Maria K., who attracts fans with her vivid ideas about the great power of the Russian language, their command of which makes the Eastern Slavs the masters of the entire Earth, according to a particular Cosmic Law (the YouTube channel has 77,000 subscribers; the Telegram chat has 6,500).

That evening, I was busy with work that is familiar to many anthropologists of religion, one that demands significant intellectual and emotional effort: I was trying to imagine the people with whom I was interacting in the field, not as “repugnant cultural others” (Harding 1991) but as “suffering subjects.” These minorities—a majority of whom adhered to extremely conservative views (compared to the views that are typical for the academic environment at my liberal university)—offered a stubborn but not-very-effective resistance to the larger society with its globalism, neoliberal economic system, consumerism, and other aspects of modernity today. Even when the members of these groups belong to a nominally dominant majority, such as the Orthodox in Russia, they usually feel marginalized, having chosen a “narrow path” in contrast to most of their contemporaries. This feeling can, of course, be represented in the idea of a “chosen people” (1 Peter 2:9), but more often it manifests in the bitter experience of what Nietzsche called ressentiment. This is when a person senses how helpless he is at solving the problems most important to him, and finds a solution in creating for himself an image of a powerful enemy whom he begins to blame for everything and to genuinely hate. Ressentiment sometimes presupposes a form of escapism, when people—religious believers, in this case—try to minimize their dependence on the larger secular world even while remaining in it, because they have no access to resources that could help them forge an autonomous existence.

In my article, I wanted to discuss how the actions of the official medical world during the pandemic—relying on the power of the modern state—were so decisive and effective that they easily tore down the invisible and (as it turns out) flimsy walls behind which people who did not trust the larger world had tried to preserve their own worlds. An acute sense of helplessness gave rise, in many, to a previously unprecedented protest against a system of governance that did not allow people to make decisions about their own body, health, and fate. I was trying to imagine the people who had waged partisan warfare for two years against an enormous machine forcing them to quarantine and get vaccinated, not as superstitious reactionaries but as desperate heroes who were trying to tell the world that more important and more terrible things exist than infectious diseases and the possibility of dying from them. In the correspondence within these groups of people I knew, I was searching for—and finding—evidence that this interpretation of antiquarantine resistance was quite rational and, in anthropological terms, humanistic. This was all about cultural relativism and an effort to understand the other, wasn’t it?

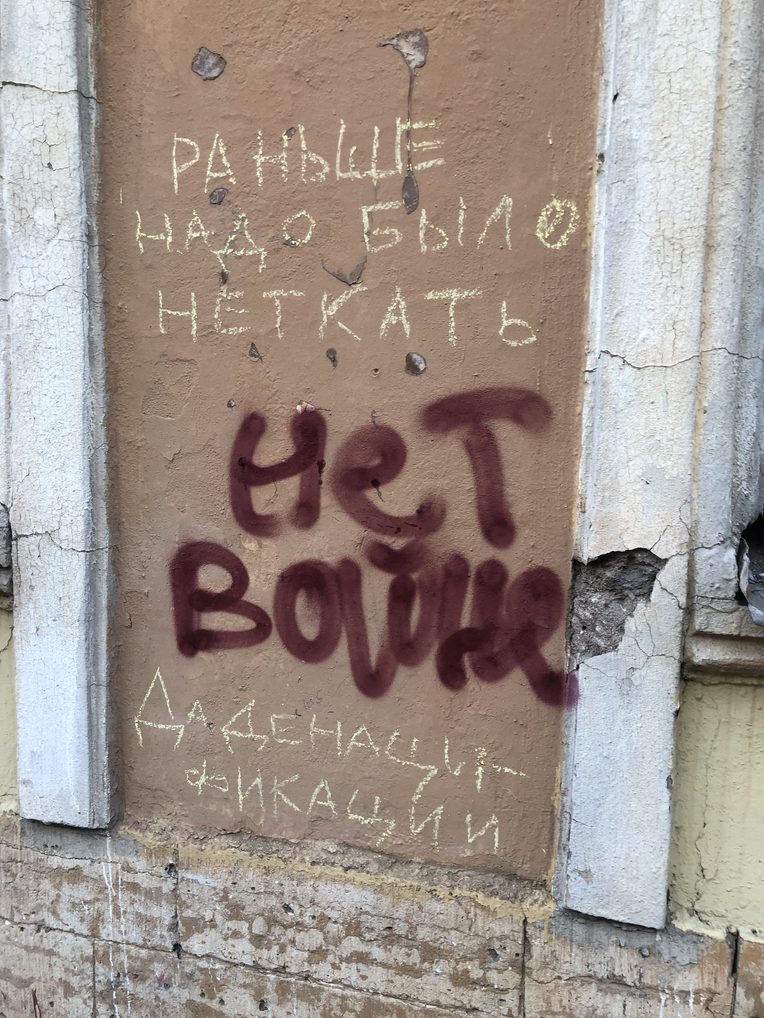

On the morning of February 24, my work on that article stopped. That morning brought a sense of terrible, irreparable tragedy into the lives of many. I tremble inside thinking about how tragic this day, and the following days, were for those living in Ukraine. These feelings pushed me, and many people I know, to protests in the street. On that day, it did not occur to me that anyone could understand the situation differently. It seemed that almost everyone would take a stand against Putin’s decision. But by that evening, it was clear that we had been deceiving ourselves. Several days of protests resulted only in multitudes of detentions (a majority, by the way, were detained and arrested not for their political activism but for violating quarantine rules). Eventually, people stopped going to the squares. In the silence that set in, the sounds of the triumphant marches played by government-controlled media, muffled before, became more audible to me. And a question occurred to me: Was social anthropology in Russia possible anymore, after February 24?

On March 10, after a long break, I opened my laptop and looked at the messages posted in the three groups I mentioned earlier. I had no idea what I would find there. Each of them was an opposition group in its own way, and I thought that sending Russian troops into Ukraine would trigger at least some protest among them.

I was shocked by what I saw. Triumphant marches poured off the screen. The members of the Orthodox and nativist groups were openly celebrating. They cheered Russia’s direct military intervention in the affairs of another country almost as if it were their personal victory, like the natural and long-awaited result of their many years of work praying and preaching. People who had spent many years eschewing all official propaganda filled the spaces of their online interactions with portraits of Putin and poems supporting him. Messages about new prophecies from Orthodox church elders convinced readers that the military actions were just and that the Russian soldiers would have an inevitable, if difficult, victory. I realized, my heart heavy, that this celebration was a direct consequence of that feeling of ressentiment that had defined the worldview of these people all these years. They were celebrating the victory of spirituality over materiality, the reign of idealism (it didn’t matter what kind) over rationality, revenge for years and decades of life lived according to the rules of cold international legal norms. These people couldn’t hide (and didn’t want to hide) their exultation. Now, finally, the political elite of their country had joined them to take action in the field where, they believed, they were especially powerful and experienced: the field of historiosophic moralizing. This conviction of their own moral superiority was built on the idea that their perceived enemies (the West, the “fifth column,” those who believed individual rights had primacy over the nation’s interests) always relied on rationality and pragmatic calculations in all their actions. And this automatically means that these rationalists are incapable of any moral feeling, moral judgment, or moral behavior.

Only Maria K., the flamboyant “Citizen of the USSR,” and her supporters spoke out firmly against the war. She said directly that an analysis of the current situation must rely on the power of reason, and reason told her that this war was organized not by the Slavs but by the people who could afford to “use their shekels” to buy all the world’s political leaders. In her words, “both Putin and Zelensky receive instructions from the same synagogue,” and the war was necessary for them to establish a “New Khazaria.”

I don’t think I’ll ever finish writing my article on COVID-19. Most of its protagonists are far too happy now for anyone to describe them as “suffering subjects” whose voices are almost inaudible to the “big, cruel world.” Their quiet prayers turned out to be indistinguishable from the speeches made by the official ideologues of the “Russian World.” And evidently, no social anthropology is necessary to analyze them.

Postscript: In many WhatsApp groups there is a habit of wishing each other a good morning by sending e-cards. They show either something sweet (like a bouquet of flowers), something sacred (an image of the Savior or the Virgin Mary), or something both sweet and sacred (a rural landscape with a beautiful church). They come with an inscription like, “Happy New Day. May God bless you.” I get cards like this from the moderator of the Orthodox group as well. This morning it wasn’t Christ or a sweet angel who smiled at me, but President Putin: “Good morning. All will be well with Russia!” A minute later a member left the group. I don’t know why.

Translated from Russian by Shelley Fairweather-Vega.

Harding, Susan. 1991. “Representing Fundamentalism: The Problem of the Repugnant Cultural Other.” Social Research 58 (2): 373–393.