SIN CESAR: Extractos de qué es, de cómo se hizo o más bien por qué lo hicimos

From the Series: Haptic Encounters of the Extrajudicial Kind: A Review Forum on the Photo-Book "Sin Cesar"

From the Series: Haptic Encounters of the Extrajudicial Kind: A Review Forum on the Photo-Book "Sin Cesar"

English Translation below

Lo más perturbador del espanto es que no constituye una excepción. Quizás por eso se escribe tanto sobre violencia y no por impulso contra su injusticia.

Sin Cesar es un relato de violencias. Una historia de incomprensión que deviene en vertientes, porque algunos libros no se escriben porque se sepa algo, sino para saberlo. Era mayo de 2018 cuando viajamos al lugar de los hechos, al lugar exacto donde aparecieron tres cuerpos muertos que el ejército asesinó e hizo pasar por guerrilleros en un falso combate[1], un “falso positivo”[2]. Allí comenzó este libro, sin saberlo y sin predisposición para ello. En el Copey, departamento del Cesar, Colombia, buscando unas coordenadas. Buscando al tiempo, un género, una manera de contar, que correspondiera a nuestro modo de ver el mundo. A cómo transmitir ese primer lugar que nos evocó una memoria convulsa sin ponerla a la vista.

Aquellos primeros días solo contemplábamos el escenario del crimen, ajeno a aquello que lo hizo posible. Solo mirábamos. Abrumados por el paisaje, por la emoción, conscientes de que las palabras son a veces demasiado escandalosas para hacer eco al silencio, y a la vez demasiado opacas como para referirse a la vorágine de la existencia (F. Melchor 2018, 9). Mirando con nuestros cuerpos y con el lente de una cámara fotográfica, hasta que el testigo apareció, y con él, también las palabras:

La voz se precipita hacia su silencio si no hay una escucha que llama, reclama o añora escuchar la palabra obstinada. Esa que pone las heridas del tiempo. Esa que narra.

La historia(s) de Sin Cesar nace de un hecho concreto en tiempos distintos. Una exhumación. Un encuentro. Un crimen de Estado. Una desaparición. Un “falso positivo,” que eran 3, que fueron más de 30. Narrados para trascender el hecho, al centrarse en la experiencia de quienes se topan con el rostro de la avaricia, la brutalidad, la impunidad o su corrupción, con la dimensión de la violencia rebasando cualquier relato anclado en la cordura, los números que creen describir el mundo, los testimonios o la denuncia.

La historia(s) es real. La de un campesino. La de muchas familias. La de gente que fue asesinada, desaparecida. La de quien disparó. La de quien buscó. La de quien quiso encontrar. La de quien quiso ocultar. La de quienes viven sabiendo.

Sola cada historia(s) pudo ocurrir en cualquier otro lugar. Pero esta historia(s) ocurrió aquí. Es real, aunque las historias, como ya lo señaló Sartre, no las cuenta la realidad, las cuenta el lenguaje humano y la memoria, la cual no se limita a conocer las cosas sino a pensar desde ciertos valores. Por eso narramos también a partir de “los recuerdos, sabiendo que estos no son un relato apasionado o impasible de la realidad desaparecida, sino que son el renacimiento del pasado, cuando el tiempo vuelve a suceder” (S. Alexiévich 2015, 15).

La memoria crece, extiende sus ramas, entre el presente y un tiempo que le precedió. Y aunque deseemos a veces que el silencio nos golpee y nos enrede, el horror y el dolor anuncian que se quedan, miran al tiempo de atrás buscando cuándo fue que se dañó el futuro.

Por ello, recordar es en sí mismo un acto creativo y situado, como Sin Cesar. Redactamos la vida, agregando o borrando líneas e imágenes. Narramos nosotros/as, y quienes nos narraron a nosotros/as, a partir de los recuerdos moldeados por el tiempo, obedeciendo consciente o inconscientemente a eslóganes, tendencias, modas, políticas e intereses. La vida, nuestra vida, su vida, se cuela entre nuestros recuerdos. Lo vivido, lo leído, lo visto. Es por eso como afirmaba Úrsula K. Le Guin (2018) que buena parte de lo que consideramos experiencia, memoria, conocimientos ganados a pulso, historia, son de hecho ficción.

¿Será entonces que todo es ficción en cuanto usamos el lenguaje para comunicarnos (Clarice Lispector)? Quizás, pero ya advertía Juan Villoro que no midiéramos los textos por su apego a la realidad, cuando son los relatos los que nos permiten vincular realidades para entender mejor y hacer más amigable el complejo y contradictorio mundo en el que vivimos, quedando insertada la idea de que la ficción, que no es lo mismo que la mentira, es otra verdad diferente que sirve para desentrañar las otras verdades posibles que no se ven en la superficie. Porque moldeamos la experiencia en la mente para darle sentido. Obligamos al mundo a ser coherente, a que nos cuente una historia.

Somos narradores, actores, creadores y también testigos. Tensión que quisimos problematizar en Sin Cesar, sabiendo por tanto que en demasiados casos las palabras nos alejan de la verdad y para otros muchos no las tenemos. Por eso, la necesidad apremiante de romper con el uso del carácter marginal de la imagen en las Ciencias Sociales, creando un espacio de encuentro y reflexión en el que dialogasen, necesitándose la una a la otra, la fotografía y la etnografía. El testimonio novelado y el textual. El diseño y su contenido.

Así en Sin Cesar hay estrategias etnográficas, hay técnica fotográfica, hay uso del archivo, hay montaje, escritura narrativa y diseño. Y hay subjetividad, tanta como angustia merece la realidad (Adorno), y así por mucho que se busque no se encontrará el “ideal de la pureza inhumana” (Le Guin 2018, 32) que es la observación.

Tras aquel primer encuentro, la historia(s) de Sin Cesar arrancó de esa vivencia personal, pero no por ello careciendo de pretensiones teóricas, de rigor analítico o de presencia epistemológica, queriendo además transcender lo meramente documental, en tanto discurso de verificación.

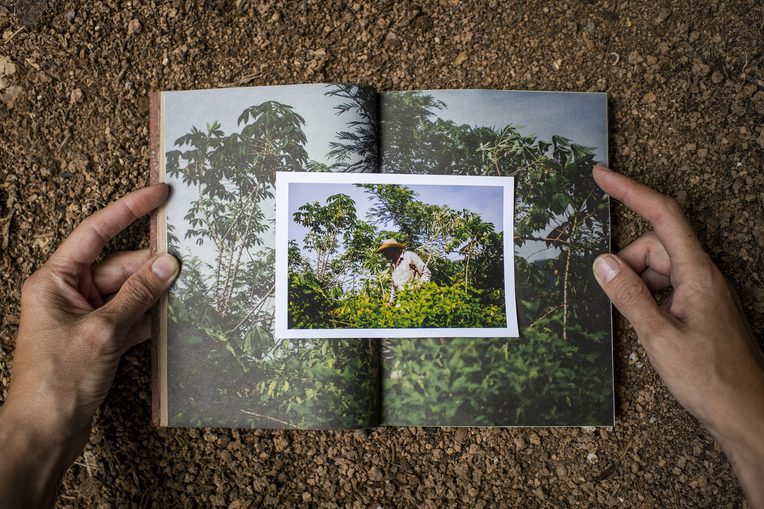

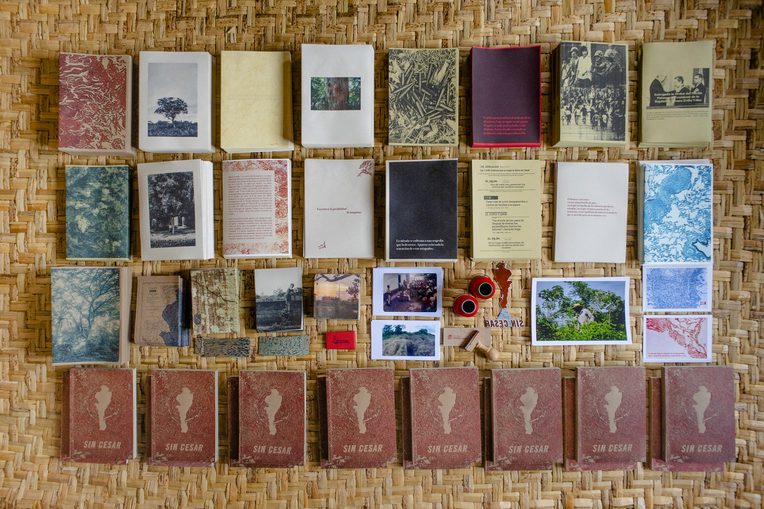

La apuesta por la que optamos, una hibridación discursiva sin paginar enfrentando al lector/a, como en la vida, a buscar por si mismos, a perderse y a encontrarse con la fuente más primaria, con ese diálogo de saberes de muy distintas disciplinas, donde las formas del relato, incluida su estética, buscan ampliar las dimensiones de los propios relatos. Lo que requirió escoger la técnica de inscripción, si de perdurar y compartir se trata, un soporte que se volvería problemático y manipulable, como un archivo. Algo, que pudiera componerse de muchos registros. Como lo es un libro artesanal, hecho con nuestras manos.

Porque Sin Cesar lo imprimimos, elaboramos y cosemos manualmente en el taller de la editorial Entrelazando, lo que nos permite tejer no sólo en la narrativa sino la materialidad del propio libro, su hechura. Incluyendo fotografías de archivos sindicales, una norma, un hallazgo en un expediente judicial, un trozo de carbón - cuya mancha hace táctil la complicidad-, imágenes satelitales de las plantaciones de caña y la minería, histológicas—que develan una cartografía herida cuando al ampliar los trozos de la muerte celular ponemos nuestros cuerpos para entender la violencia en los territorios-, una corteza, logos, y un sin fin de documentos que confirmaron las sospechas ayudándonos a reconstruir la historia(s).

De hecho fue la sospecha la que orientó esta investigación, en línea con Paul Ricoeur cuando hablaba de la “hermenéutica de la sospecha” para referirse a las filosofías críticas que recelaron del orden y las verdades universales que regían el mundo y demostraron así los intereses y estructuras que lo apuntalaban.

La sospecha como incómoda inquietud, la sospecha como ejercicio de resistencia, la sospecha de cómo ocurrió, y es que no es la “verdad histórica” advertía Héctor Schmucler (2019) la que intenta olvidarse, sino la responsabilidad de preguntarse por qué el crimen se hizo posible.

Y es que ante el brillo, la magia y los aplausos, nos tenemos que preguntar si al lado no hay horror, dolor y víctimas. Un cuestionamiento constante que en palabras de Juan Felipe García interpretando la teoría de Mick Taussig, sería un “montaje contra un montaje,” eso es para él Sin Cesar, al desvelar ese momento fulguroso de los héroes, para (de) mostrar que si alguien se quedó con unas tierras es porque exterminó a todos lo que tenían un proyecto de vida diferente.

Un montaje que busca amplificar un contrarelato que desafía, entre otras cuestiones, al statu quo de lo que es un “falso positivo,” de cómo se viene narrando desde un relato simplificador e incluso afín al Estado perpetrador, que justifica su accionar delictivo por unos incentivos, premios o ascensos, reduciéndolo a unos pocos, a “un quiebre ético corporativo” [3], y no a una política de Estado sistemática que viene sucediendo en casi todos los departamentos del país desde hace décadas, y que según el caso aquí abordado, su propio testimonio, tiene claras conexiones con las violencias territoriales, con la expropiación de los recursos, con el paramilitarismo, con la riqueza de unos pocos.

Los libros, construyen comunidad a su alrededor, expresa Cristina Rivera Garza (2022). Porque ni leemos, ni escribimos solos/as, sino que lo hacemos siempre con otros “enlazados por los hilos de un lenguaje que nos constituye y nos nutre y, en diferentes casos, nos limita o nos libera.” Y más aún cuando estos son distribuidos por sus autores, como Sin Cesar, de manera que todavía se abren más posibilidades a su vida social.

Esa es la apuesta de Entrelazando, hacer libros, que finalmente dejen el ejercicio en el lector/a de decir qué es SIN CESAR o de operar en su ambivalencia frente a la injusticia.

What is most disturbing about this horror is that it is not an exception. Perhaps that is why so much is written about violence and not out of impulse against its injustice.

Sin Cesar is a story of violence. A story of incomprehension that turns into slopes, because some books are not written because you know something, but because there is a need to know. It was May 2018 when we traveled to the site of the events, to the exact place where three dead bodies showed up, three people that the army had killed and passed off as guerrillas in a false combat [1], a phenomenon known as “false positives”[2] . That is when this book began, without knowing it and without any predisposition to do so. In El Copey, department of Cesar, Colombia, looking for coordinates. Looking for a genre, a narration style that would corresponded to our way of seeing the world. Looking to transmit that first place evoked a convulsive memory without putting it in sight.

Those first days we only contemplated the scene of the crime, oblivious to how it happened. We just observed. Overwhelmed by the landscape, by the emotion, aware that words are sometimes too scandalous to echo the silence, and at the same time too opaque to refer to the maelstrom of existence (F. Melchor 2018, 9). Looking with our bodies and with the lens of a camera, until the witness showed up, and with him, so did the words:

The voice rushes towards its silence if there is not a listening that calls, claims, or longs to hear the stubborn word. The one that puts the wounds of time. That which narrates.

The story(ies) of Sin Cesar stems from a specific event in different times. An exhumation. An encounter. A State crime. A disappearance. A “false positive”: that there were three, that there were more than thirty. Narrated to transcend the fact, by focusing on the experience of those who encounter the face of greed, brutality, impunity or its corruption, with the dimension of violence surpassing any story anchored in sanity, or numbers intended to make believe they describe worldly events, the testimonies or the denunciation.

The story(ies) is true. That of a farmer. That of many families. That of people who were murdered, disappeared. That of the shooter. Of those who searched. That of those who wanted to find. That of those who wanted to hide. That of those who live knowing.

Every single story(ies) could have happened anywhere else. But this story(ies) happened here. It is real, although stories, as Sartre already pointed out, are not told by reality, but by human language and memory, which is not limited to knowing things but to thinking from certain values. That is why we narrate also from “memories, knowing that these are not a passionate or impassive account of the vanished reality, but are the rebirth of the past, when time happens again” (S. Alexievich 2015, 15).

Memory grows, spreads its branches, between the present and a time that preceded it. And although we sometimes wish that silence would strike us and entangle us, horror and pain announce that they remain, they look back in time looking for when the future was damaged.

Therefore, remembering is in itself a creative and situated act, like the whole endeavor of Sin Cesar demonstrates. We baked life into the book, adding or deleting lines and images. We narrate on our terms, and those who told our story, from memories shaped by time, consciously or unconsciously obeying slogans, trends, fashions, politics, and interests. Life, our life, their life, slips into our memories. What we have lived, what we have read, what we have seen. That is why, as Ursula K. Le Guin (2018) wrote, much of what we consider experience, memory, hard-won knowledge, history, is in fact fiction.

Could it be then that everything is fiction as soon as we use language to communicate (Clarice Lispector)? Perhaps, but Juan Villoro warned us not to measure texts by their attachment to reality, when it is the stories that allow us to link realities to better understand and make more friendly the complex and contradictory world in which we live, inserting the idea that fiction, which is not the same as a lie, is another different truth that serves to unravel the other possible truths that are not seen on the surface. Because we mold experience in the mind to make sense of it. We force the world to be coherent, to tell us a story.

We are narrators, actors, creators, and also witnesses. Tension that we wanted to problematize in Sin Cesar, knowing therefore that in too many cases words take us away from the truth and for many others we do not have them. Therefore, the pressing need to break with the use of the marginal character of the image in the Social Sciences, creating a space of encounter and reflection in which photography and ethnography would dialogue, needing each other. Novel and textual testimony. The design and its content.

Thus in Sin Cesar there are ethnographic strategies, there is photographic technique, there is the use of the archive, there is montage, narrative writing, and design. And there is subjectivity, as much as an anguish deserving reality (as Adorno would say), so no matter how hard one searches one will not find the “ideal of inhuman purity” (Le Guin 2018, 32) in observation.

After that first encounter, the story(ies) of Sin Cesar started from that personal experience, but not for that reason lacking theoretical pretensions, analytical rigor, or epistemological presence, also wanting to transcend the merely documentary, as a discourse of verification.

The endeavor we opted for, a discursive hybridization without compelling the reader page by page, as in much of life, to search for themselves, to get lost and to find themselves with the most primary source, with that dialogue of knowledge from very different disciplines, where the forms of the story, including its aesthetics, seek to expand the dimensions of the stories themselves. This required choosing an inscription technique, a material affordance that would raise issues and allow for diverse handlings, like an archive. Something that could be composed of many records. Like a handmade book, made with our hands.

Because Sin Cesar is printed, produced and sewn by hand in the workshop of Entrelazando's publishing workshop, allowing us to weave not only the narrative but also the materiality of the book itself, its imprint in the world. Including photographs from union archives, a norm, a finding in a judicial file, a piece of coal—whose stain makes complicity tactile—, satellite images of sugar cane plantations and mining, histological—which unveil a wounded cartography when enlarging the pieces of cellular decomposition—, a bark, logos, and endless documents that confirmed the suspicions helping us to reconstruct the story(ies).

In fact, it was suspicion that guided this research, in line with what Paul Ricoeur calls the “hermeneutics of suspicion,” referring to the critical philosophies that distrusted the order and universal truths that governed the world and thus demonstrated the interests and structures that underpinned it.

Suspicion as an uncomfortable uneasiness, suspicion as an exercise of resistance, suspicion of how it happened, and it is not the “historical truth” that Héctor Schmucler (2019) warned could fall in oblivion, but the responsibility of asking why the crime was made possible in the first place.

And before the brightness, the magic, and the applause, we have to ask ourselves if the horror, the pain, and the victimization persist. A constant questioning that, in the words of Juan Felipe García interpreting Mick Taussig's theory, would be a “montage against a montage.” For him, Sin Cesar pokes the veil of the shining moment of military heroes, demonstrating that if someone were to usurp land it is because extermination ran its due course against all who had a different understanding of what inhabiting the land entailed.

A montage that seeks to amplify a counter-narrative that challenges, among other issues, the statecraft around the definition of “false positive,” how it has been narrated from a simplifying story and even akin to the perpetrator, which justifies its criminal actions by incentives, awards or promotions, reducing it to “a corporate ethical breach,” and not to a systematic State policy that has been happening in almost all departments of Colombia for decades. According to the case addressed here, in its own testimony, there are clear connections with territorial violence, with the expropriation of resources, with paramilitarism, with the wealth of the few.

Books build community around them, says Cristina Rivera Garza (2022). Because we neither read nor write alone, but always with others “linked by the threads of a language that constitutes and nourishes us and, in different cases, limits or liberates us.” And even more so when these are distributed by their authors, like Sin Cesar, in a way that opens up even more possibilities for their social life.

This is, in sum, what Entrelazando's project entails, to make books that leave the task of unveiling injustice in the reader's hands, or rather to have them make sense of what SIN CESAR is in their own view and to make its broad signifiers operational in the face of rampant impunity.

1. All phrases and words in italics are from the book Sin Cesar (Ed. Entrelazando, 2020).

2. “Extrajudicial executions [by the Colombian army]. State violence. Often, or sometimes, in collusion with paramilitaries. Fake combat scenarios. Change of clothes, boots freshly put on, shots in the trees, weapons put on once dead. All in the legality of a supposed combat, which requires the lifting of the bodies and all its officialdom, testimonies, burials, protocols and therefore also a legislation and an apolitical that endorses it. A criminal system that allows and prosecutes it. And all the unimaginable complicities” (Sin Cesar, 2020).

Alexiévich, Svetlana. 2015. La guerra no tiene rostro de mujer. Madrid: Penguin Random House.

Langa Martínez, Laura, and Ariel Arango Prada. 2020. Sin Cesar. Bogotá: Editorial Entrelazando.

Le Guin, Ursula K. 2018. Contar es escuchar: Sobre la escritura, la lectura y la imaginación. Spain: Circulo de Tiza.

Melchor, Fernanda. 2018. Aquí no es Miami. Mexico: Literatura Random House.

Ricoeur, Paul. 1975. Hermenéuica y estructuralismo. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Megápolis.

Rivera Garza, Cristina. 2021. “Speech for the Nuevo León Alfonso Reyes Award,” organized by the UANL, the Tecnológico de Monterrey, the Universidad de Monterrey (UDEM), and the U-ERRE, in conjunction with the Government of Nuevo León, through Conarte and the state Ministry of Culture.

Schmucler, Héctor. 2019. La memoria, entre la política y la ética: Texos reunidos de Héctor Schmucler (1979-2015). Buenos Aires: CLACSO.