Sin Cesar: The Healing Potency of a Book

From the Series: Haptic Encounters of the Extrajudicial Kind: A Review Forum on the Photo-Book "Sin Cesar"

From the Series: Haptic Encounters of the Extrajudicial Kind: A Review Forum on the Photo-Book "Sin Cesar"

Even as one who dreams that he is harmed

and, dreaming, wishes he were dreaming, thus

desiring that which is, as if it were not,

so I became within my speechlessness:

I wanted to excuse myself and did

excuse myself, although I knew it not.

Inferno. Canto XXX: 136–141

Translated by Alex Liebman

I will try to explain why Sin Cesar is a talisman. It is at once an object endowed with will and an instrument to protect itself from terror. The first thing to understand is that Sin Cesar is much more than just a book. The book format functions as an excuse, channeling a multiplicity of voices, images, and movements that persist in an environment saturated by “analysis” and “narratives” about the “armed conflict.” In this environment, sensitivity is sacrificed for explanation. Laura and Ariel have achieved something extraordinary with this magical artifice, telling a story of dispossession and forced disappearance in the department of Cesar in northern Colombia.

Among the many possible ways of approaching something as aberrant as State terror, they chose to weave. And the fabric is the key. In Sin Cesar we find a fabric in which the vegetable and the animal intertwine. We see the fragments and illuminations of that lattice of the life. Connections come to us through images, texts, and textures. The intimacy of the words is not accidental. Here one finds the blood that persists in memory, the bark with its scars, and the mineral bed of prehistoric streams.

Each page opens like a hole of light in the darkness that disappears instantaneously akin to Walter Benjamin’s “profane illumination” Begin with the cover. In relief, the sketch of the department of Cesar and in sustained capital letters the title of the book. In the surround, color and figures. At first it looks familiar: maybe a map, maybe a satellite photo, maybe the bark of a tree, maybe a pool of blood. We do not understand. From here on, we can expect a path of discovery.

Undoubtedly, the authors—who independently published the entire book, including its design and manufacture—have thought carefully over the composition of each page and the aesthetic and political meaning of each transition. Let’s pause to consider just the first six pages: the blood/bark/bed, people in movement and the earth with the sky. We are already located, with two turns of the page, in the center of this story.

And, as we continue to turn the pages, each one of these threads tightens and opens. Words are dissected to find their secret mechanisms. First it happens with “Cesar,” then with “Copey” (later with “Execution” and finally with “Archive”): text, image, map, photograph. The primordial elements have been put upon the table. And then a disconcerting transition occurs, perceived with the eyes and fingers: here the type of paper and the color change, opening the way to the first chapter.

The lyrical prose of the chapters, in turn, also rises like a vocal torrent, like a flush of roots that sprout from the ground (which is memory) and at the same time seek the fresh surface (which is language). Narrative moves from first to third person in a complex flow. A few words appear, disperse words, but when we understand what “in the center, always violence” means, we discover their combined strength.

Now a man moves between gigantic cassava bushes. In the middle of the two pages a red thread crosses his face, shadowed by a straw hat. “It is necessary to speak, fear steals our words.” It is the anticipation of the terror that falls over the following pages.

As a book about terrorism of the State, it is faced with the permanent danger of the banality of horror. But—surprise!—this is not an official report on historical memory. It is about something much more important, something akin to healing.

A fiber paper covers two small chronicles of May 2018 at two key moments of the book. Why? It seems to protect the words between cotton like a thick veil. Like a knot in the throat and retina, it later comes loose onto the thick paper with cryptic texture. They speak to us of voices and of bodies, of violence, deceit, disappearance, and the search. It is the exact opposite of banality.

The search. What story do so many trees narrate? They are witnesses with a language from another time, almost imperceptible, only communicable by the vestiges of violence traced on their surfaces. The red markings, the bullet holes, the runes of sun filtering through the tall leaves of a ceiba tree.

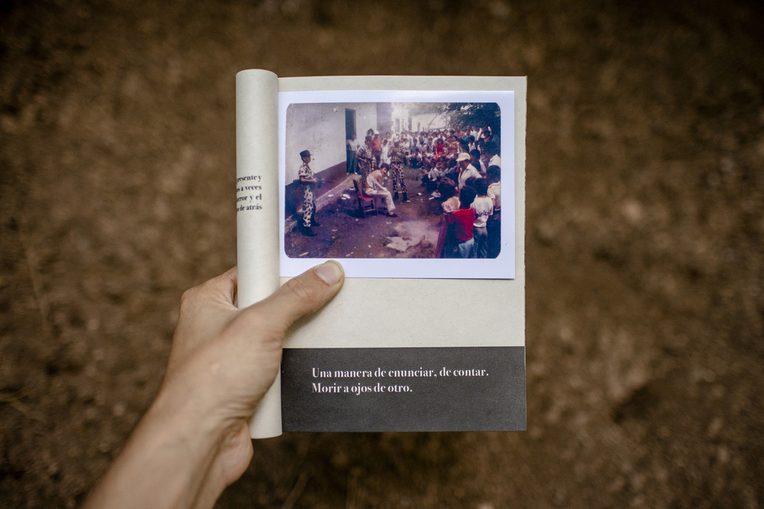

And then a new element enters, removing all else. New witnesses also carry their own language on their backs. Here the archive intertwines with what is already occurring, adding a layer of materiality to the story’s silences. We are facing the vestiges of agrarian, union, and worker struggles, exterminated to make way for progress. The classic story that is repeated at every moment in all corners of the world: primitive accumulation as a permanent process.

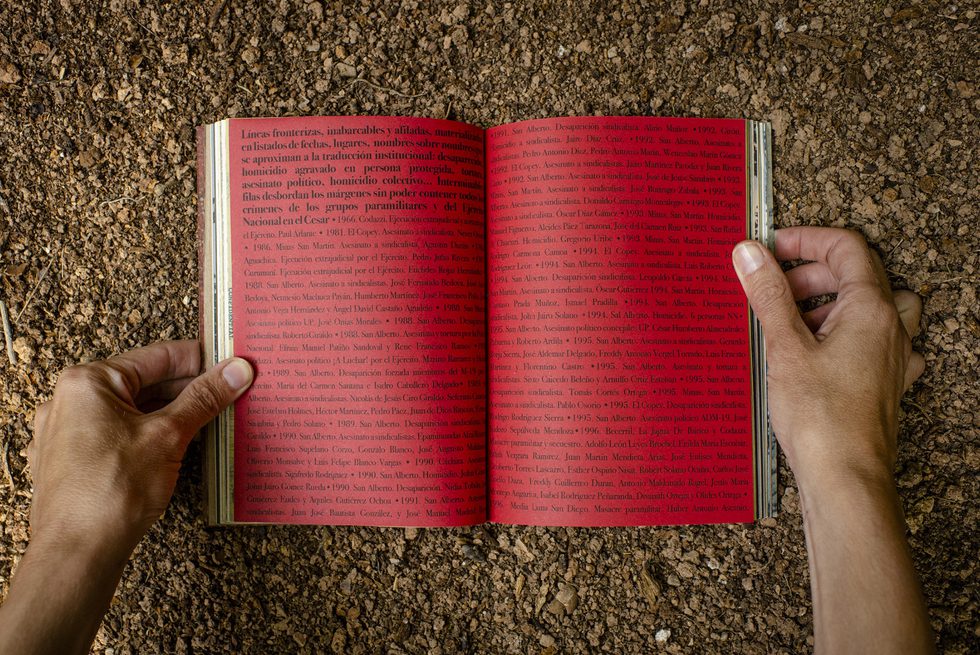

With a new turn of the page and a montage around a corpse, the relay of an indisputable fact: “extrajudicial executions” are only the perfection of a political project of domination decades in the making. In the words of the authors, what follows is “inexpressible.” The first and last names of two hundred ninety-five assassinations committed by the Armed Forces and paramilitaries in Cesar from 1966 to 2011. Six gruesome pages of thick red cardstock crammed with severed lives.

In this way, we arrive at the book’s halfway point and the center of so much death. The answer is traced through so many other fragments and moments: the many masks of progress. For Cesar, progress means African palm and coal. In thirteen testimonies, the story of a sacrifice zone is told, how development that reeks of smoke and appears like endless rows of the same plant is configured. On the one hand, the workers’ struggles for dignity; on the other, the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC, by its Spanish initials) in their impeccable uniforms. Development’s victory is overwhelming, demonstrated by aerial photos of palm plantations and coal mines.

The following part, chapter 3, is possibly the most painful. We see, in a very intimate process—barely illuminated, black and white, fragmentary texts, in a slower rhythm—a concrete case of the human sacrifice that capital demands. Again, the search. The hope of discovery. The suspicion, the contained horror, a sunset over a collapsed wall and inside the exhumation. “Even as one who dreams that he is harmed…” Dante says in Inferno, “and, dreaming, wishes he were dreaming.”

“Unceasing, the wound continues.” Closing the last pages of the book, a compendium of headlines screams the bureaucratic language with which impunity is so well disguised. The bureaucracy, always labyrinthine, appears in partial relief: it is revealed through headlines still recognizable today. But this too will pass. The time will come when they feel as far away as the photos of the union mobilization. They will be footprints.

How is this like a talisman? Without the materiality of the book, it is difficult to explain. But Sin Cesar is part of that literary kingdom that Michael Taussig calls “apotropaic writing”—that which is conjured to protect oneself from danger. Here there is a double jeopardy: the paramilitarized violence of progress and the violence of writing about violence. This is why I think the book has healing powers. It opens an important space to narrate, to listen. How often do we come across a book with this ability?

The intricately stitched inner booklets, the flyers that jump into one’s lap, the ironic prints, the folded posters, and the unexpected postcards are solely reinforcements of a sharp instrument. This tool pierces the body of those who approach it and who allow themselves to be moved by this spectral way of recounting pain. In the shade of a ceiba tree, with roots like mountains, Sin Cesar offers us a new path of intimate commitment with ongoing struggles. It tells, on the other side, lasting stories that do not betray the narrators and their experiences.

Alighieri, Dante. 2021. Infierno. Penguin clásicos. Madrid; España.