Single-handed

From the Series: HandsOn: Touching the Digital Planet

From the Series: HandsOn: Touching the Digital Planet

When I performed Beckett’s Not I in 1982, my face and neck were painted black, my lips stark white, amplifying the surrealism of the text, presentation, and staging. The challenge for me—for any stage actor—was to use my voice and lips alone, unsupported by body movement, posture, gesture, or expression. On the second of the three days on which I performed, anxious, I looked down my nose, unable to discern if my lips were visible. At the point of fainting (and this would not have been the first time), I went backstage, gulped down a cup of very sweet tea, returned and began again. Given the text and staging, my absence might have been interpreted as part of the performance.

In Not I the actor relies on voice and delivery: on tone, projection, sound, speed, diction, precision of timing. In radio, podcast and internet interviews, in contrast, although the voice is dominant, there are acoustic props: music, background noise to capture mood, other voices that come in to clarify or contextualize.

For me, Not I fitted with anthropological puzzles of narrative, recollection, and reverie. The life of the unnamed woman in Not I is not so different from testimonies that as anthropologists, we gather from people whose lives are, they say, “nothing of note,” constrained, ruptured, and so troubled that it is barely possible for them to speak at all. In interviews and idle chat, people tell us parts of a story, not others; we search for the logic that people give to their life stories at a certain point of time. As practitioner ethnographers, we worry about interpretation and editing.

The syntax and perseverations in Not I are the stuff of interviews, especially when interlocutors speak of that which is unspeakable. Here posture and gesture play important communicative roles. Our interlocutors and we all slump, shrug, shift, and shuffle through acts of speech. We hide our face, pick at a blemish, cover our eyes, wipe tears; we blink, wink, and sideways glance. We sway, step back, and especially, we use our hands, with and sometimes against our voices. Perceptible tension, clench and carry, grasp, and the tremble of fingers all complement the reception of voice, and support or worry interpretation. The challenge for the actor in Not I, like a zoom interview in the present, is precisely this: the body, hands especially, are unavailable for interpretation and effect.

Any change in corporeality ushers in existential reckoning and social re-evaluation, the risk of exclusion or the hope of inclusion. Those whose bodies change in undesired and derided ways, or newly become aware of their bodies as unusual, face particular challenges to common meanings of physical configuration and confinement. People speak of being ‘normal’ as they grapple with essentialist notions of worth and the tensions of corporeality and intellect, body and soul. We seek to redress bodily impairment through prostheses, physical therapy, and surgery (Grealy 1994); we work to accommodate changes in function, structure, sense, and proprioception (Manderson 2005, 2011; Manderson and Smith-Morris 2010). We take on appurtenances, including instruments incorporated into and muted by the body—a stent, an interocular lens, a dental implant—and other technologies that become part of an everyday habitus—spectacles, a hearing aid, an artificial arm and hand. Some of these changes are so quotidian that the landing in new form is very soft. Others, like the removal of a body part, or sudden functional decline or loss, require people to work assiduously to normalize their reconfigured self.

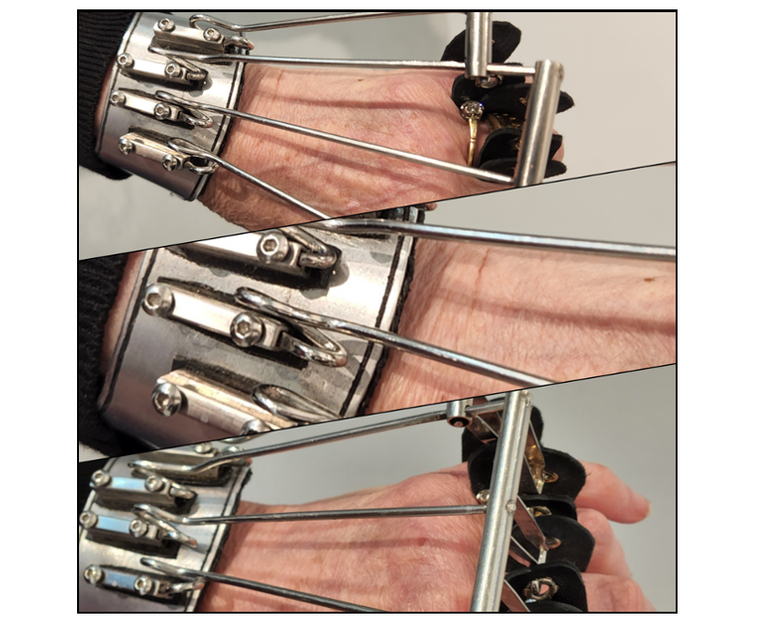

On my left hand, I wear a brace of aluminum, stainless steel and leather. Neither obviously jewelry nor prosthetic, it attracts and confuses. It invites engagement, though; it is a vehicle of introduction, story-telling, and memoir. But my brace and I are not fungible. Perplexed by the unexplained palsy, people look for palliation: Are you right handed? they ask. Well, yes. Good, then. Try getting up each morning with one hand.

Regardless of what we do, the vast, vast majority of us use our hands to work. We rely on hand motility, power, strength of grasp and clench, prehensility, dexterity; we support ourselves to balance with our hands and arms. Everyday self-care, care for others, cooking, cleaning, gardening, gathering, carving, drawing, writing . . . we do “do verbs” largely with our hands. When I lost the use of my left hand, I lost my repertoire of communication. A one hand gesture, a single flay, uneven grip, a pitch to the right, drew attention to the absence; my left hand became a spectacle that I had to work around. And I lost speed: one hand typing, one hand cooking, one hand clapping, these are slow hard tasks.

The resolution of my indisposition was a consequence of connection and good fortune, class and setting. For this reason, the story lacks the drama, uncertainties, self-revelation and existential resolution that characterize medical memoir and ethnographic story telling. The usual account, the one I tell, is less of my body and myself, and more of the brace as curiosity, artefact, and art work. The brace granted me and others permission to engage with bodily difference, through its independent life, its own provenance and pathways. Meanwhile, for me, it built social capital: it invited comments, smoothed over inequalities in the field, created a space for everyday conversation. People routinely admired it, and I basked in its glory. It gave me a new vocabulary, confidence and presence. It amplified my voice. But while I used the device intentionally as an object of beauty, to push against notions of the “disabled” body as all-defining and disability as abject, now I had conspired in and conceded to the brace’s definitional powers. At the same time, the brace is beautiful; I took advantage of my class and available cash, aesthetic capital, and social connections to create an object of desire that distanced me from others whose disabilities could not be so cleverly morphed.

With the demise of my radial nerve, I found the nerve to manage nerves and nervousness. Through serendipity, the nerve’s lost function and the replacement brace enabled other connections—nerve lines—with individuals and places. The brace, rather than a metonym of a ruptured nerve and inert fingers, carried me forward, activating other nerve lines to make things happen. Literal and metaphoric nerves converged, with evolving connectivities and fiber lines. The making of my distinctive, permanent brace, then making the documentary film Nerve (Woodson 2008), added to my insight that complicated my work on chronic conditions and disability.

The brace and its associated storytelling suggest the entanglement of materials, products, and acts of thinking, provoking and distilling. Ceremonial and everyday materials all enable alternative narratives of the body and self-perception, aesthetics, science and commerce. Individual artists have routinely used their own and other bodies to articulate personal crises and contradictions of the body, pushing bodily boundaries to critique the cultural environment that constructs meanings of the body and its demise. Other materials, artefacts and processes support us to operate in the world, offering them new vocabularies and grammars to engage in social life. They became the hands that carry the work of social life.

Grealy, Lucy. 1994. Autobiography of a Face. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin.

Manderson, Lenore. 2005. “Boundary Breaches: The Body, Sex and Sexuality Post-Stoma Surgery. Social Science & Medicine 61, no. 2: 405–415.

Manderson, Lenore. 2011. Surface Tensions: Surgery, Bodily Boundaries and the Social Self. Walnut Creek, Calif.: Left Coast Press.

Manderson, Lenore, and Carolyn Smith-Morris, eds. 2010. Chronic Conditions, Fluid States: Chronicity and the Anthropology of Illness. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Woodson, Wendy. 2008. Nerve: Conversations with Lenore. Amherst, Mass.: Present Company Inc.