In I Swear I Saw This, Michael Taussig (2011) chronicles his travels in Colombia through his mostly colorless drawings. He writes that he is “not much of a drawer,” though the drawings do, for Taussig, possess vigorous and carnal modes of being; they “come across as fragments that are suggestive of a world beyond, a world that does not have to be explicitly recorded and is in fact all the more ‘complete’ because it cannot be completed. In pointing away from the real, they capture something invisible and auratic that makes the thing depicted worth depicting” (Taussig 2011, 13). Here, drawings (and sketches, in particular) unfold as intimate and slightly arcane forms of cultural expression, embracing mimesis and its affective and magical qualities. Sketching entails not a reproduction of reality, but the avowal “I swear I saw, felt, and heard this.”

The anthropologist may draw, but drawers make audiovisual ethnographies too. Illustrator Judit Ferencz, for instance, sketches everyday encounters in Robin Hood Gardens, an East London housing estate (for U.S. readers, public housing complex) that is currently being demolished for eventual redevelopment. From their evocations of domesticity to the residents’ inventive use of public space, her drawings breathe an atmosphere of affection and familiarity. They capture gestures of cooking and play, and many are marked by a specific interest in the architectural details that shape the chores of those portrayed: from cupboards and door hinges to archaic stoves and waving curtains, these minutiae suggest that the estate is made up of lived spaces, rather than sites that urgently require intervention by urban planners and policies.

With her sparing pencil strokes, Judit Ferencz transforms a housing estate into a collection of homes, paying the utmost of attention to those who are dwelling within tthem. Though trained as an illustrator and currently completing a PhD in architectural design, Ferencz points in her work toward forms of praxis in a way that borders on anthropology. Her work, in short, presents a remarkable counterpoint to Taussig’s sketches. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of an interview that contributing editor Sander Hölsgens conducted with Ferencz about her working methods and how these might resemble the conduct of visual anthropology.

Sander Hölsgens: What brought you to research Robin Hood Gardens, and how did you get to know its residents?

Judit Ferencz: Robin Hood Gardens is a unique case study in that it combines the issues of social housing and, as the only realized housing project by the famous British architects Alison and Peter Smithson, issues of architectural heritage listing. It was finished in 1972 as social housing and it was refused heritage listing in 2009 and 2015. As a result, it is currently being demolished as part of a wider redevelopment scheme. I chose it specifically because of the unique combination of these issues. I am interested in processes that are often disregarded in conventional heritage practices, such as the social role of a building. This complicates the hierarchy of conservation values and offers a different temporality, embracing the complete life cycle of a building and the array of its functions across time.

Initially, I did not know anyone from the estate and drawing had a crucial role in getting to know people. This was especially true because the majority of the people who live in the estate have a Bangladeshi or Somalian background; many of the women don’t speak English and are considered to be stay-at-home wives. Since we did not share a language, drawing was a practical method for communicating with these women. It allowed me to invite people into my practice, even as it was a way for me to understand how the estate is experienced. I also think that the sketchbook and pencils created space for interaction in a more free and playful way.

SH: For anyone who conducts research on social or public housing, it seems that it would be difficult not to take a political stand on urban planning and large-scale redevelopment projects. Does your work include any commentary on these issues or do you try and shift your focus away from such themes, so as to free up space for the intimacies of everyday life?

JF: Through capturing the intimacies of everyday life, as you put it so nicely, I would like to show a different temporality than the conventional trajectories of large-scale development projects and architectural heritage decisions. Although research by University College London’s Engineering Exchange shows that refurbishment of social housing is financially, environmentally, and socially more beneficial, the councils overwhelmingly decided in favor of the demolition and redevelopment of Robin Hood Gardens. I hope that my work is sensitive to the social aspect of the demolition vs. refurbishment debate, takes into account the entire life cycle of a building, and communicates these issues to a wider, lay audience of all ages.

SH: Your drawings take on the form of sketches: you allow yourself to draw with only a few lines and even fewer colors. Yet these pieces aren’t rushed, as you show a deep interest in and attention to the smallest of gestures. I particularly revel in the drawings of a Bengali family, many of which take place in their kitchen. You show this room in its entirety, but also zoom in on the specificities of a recipe, including the cooking utensils and ingredients. Even hand movements and facial expressions are visible, which you display with the finest of lines. Could you describe the process of drawing scenes like these, and explain what appeals to you about the sketch as both a research method and an artistic mode of disseminating knowledge? Does the act of drawing create a sense of proximity to the people you work with?

JF: These drawings are of Halema, a resident of Robin Hood Gardens, who very kindly invited me to draw her preparations of a meal for a family celebration. I sat at her kitchen table drawing while members of her family were constantly passing by, looking over my shoulder to see the progress of the drawings. I still see in the drawings how I was trying to capture all of the details of the cooking, the people, and the place. It was a wonderful experience to be there and the drawings stand as a relic of that time. I remember that it was also quite stressful, as I wanted the drawings to live up to my joy of being there, as well as to the expectations of the family. Drawing certainly allowed for a greater intimacy through the moments I shared with Halema as she was cooking and I was drawing. These drawings also shaped the way that I subsequently started to approach my research methodology, where reportage is a first stage of research during which I draw without a precise outcome in mind. I then sometimes develop these drawings in another medium, such as self-made books, for dissemination purposes.

SH: You seem to go through the motions of conducting fieldwork, yet you’re hesitant to call yourself an anthropologist. What do you consider to be your field of research? Also, how has your relationship with the residents of the Robin Hood Gardens changed over time, and in what ways did this affect your working methods? Do you, for instance, attune your drawing techniques to the atmospheres and affective qualities of a place?

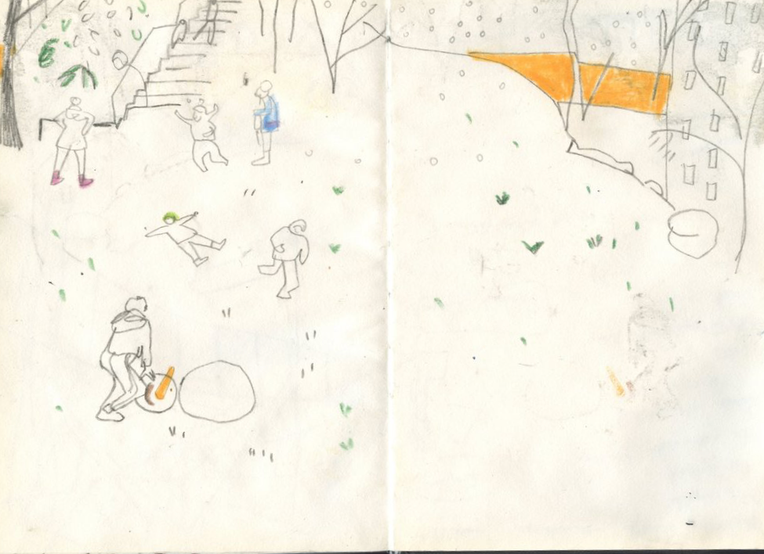

JF: I position my illustration practice within the realm of architecture, in an effort to capture and share how different historical moments and temporalities of a site can connect. This also allows me to explore how buildings guard, guide, and serve the lives of their inhabitants while they themselves have their own complete life cycle. The demolition of Robin Hood Gardens started in August 2017 and life is becoming gradually harder for the people who still live there. They are more isolated and vulnerable. I try to reflect on this in the drawings. For example, I was thinking about how one scene of children playing in the snow was framed by the orange screens surrounding the demolition area. It has also become more difficult to approach residents as a stranger, even as a stranger with sketchbooks, as the number of burglaries have increased as of late. I have taken to drawing in the social spaces of the building, such as the decks and the council offices.

SH: Michael Taussig (2011, xi), whose work I know you’ve read in close detail, is interested in the kinds of notebooks that “mix raw material of observation with reverie.” Your drawings seem to work along similar lines: they are sketches and therefore perpetually unfinished, as though they are visual reminders of your experiences, but one can simultaneously get lost in their wonderful details and configurations. Having seen a piece of yours on the Aylesbury Estate [another London estate targeted for redevelopment], your work sometimes take on the form of a dreamlike collage. I wonder how you would frame such a project. Is it a notebook, in Taussig’s sense of the word? How and for whom do you publish pieces of this sort?

JF: At the Aylesbury hearings, I could draw in a more abstract way because I was part of the audience. I felt invisible and therefore more free. Time passed very slowly as I struggled to follow the legal jargon and I think this feeling of distance from what was happening in the room might be the reason that the drawings became collage-like. I see them as notebooks in the sense that I was looking to understand the space and the event through the drawings, rather than looking to provide an accurate description of them.

I am still thinking about my audience for this kind of drawings. It usually means something to the people whom I draw or who are present when I draw; they like to identify themselves in the drawings and it is important to me to show and discuss the drawings with them. But I feel like I need to develop this work if I want to reach a wider audience. I recently made two small books that are publications developed from reportage drawings, but I still need to see if these work as I imagined them to, likely by disseminating them in council waiting rooms.

SH: Finally, what other projects are you currently working on, and are there any anthropological forms of conducting research that you’d like to explore in more depth?

JF: I am now working on a children’s picture book based on my archival research for Robin Hood Gardens. It recounts the whole life cycle of Robin Hood Gardens and each spread is a different stage in the life of the building, as told by a company of animals. I am really interested in how I can make this book interactive through workshops with resident children. Would that count as an anthropological form of research?

References

Taussig, Michael. 2011. I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.