Standing with Standing Rock

From the Series: Standing Rock, #NoDAPL, and Mni Wiconi

From the Series: Standing Rock, #NoDAPL, and Mni Wiconi

What affects one, affects all, so we stand together united.

–Nakai Clearwater Northup (Pequot youth)

We are a group of scholars and cultural workers from multiple subject positions who came together around our mutual concern for water, land, and Indigenous sovereignty. Together we convened a teach-in on #NoDAPL that was intentionally polyvocal, building on the passion and solidarity shared across local youth, elders, scholars, and community members. For us, the direct action of the water protectors underscores the need for spaces of exchange that are profoundly communal and collaborative: a circle.

In the spirit of this collaboration, we share below excerpts from our individual remarks rather than (re)write them in “one voice.” Our hope is that the different but not disparate intonations reflect the new alloys of strength that the teach-in revealed.

In the 1630s, Pequot homelands stretched across what is now eastern Connecticut, eastern Long Island and the periphery of Long Island Sound. They were the first to experience the intensity of settler desire, an avarice that culminated in the Pequot Massacre of 1637 and was followed by nearly three and a half centuries of elimination and dispossession. These are the roots of American Indian policy in North America. Today, Pequot tribal members are keenly aware of the legacy and ongoing challenges of settler colonialism in their homelands.

The recent #NoDAPL resistance movement evidences the history of struggle shared by Indigenous peoples everywhere. But through struggle comes resilience, and #NoDAPL has also precipitated a rearticulation of power that is giving voice to a new generation of youth leaders. In Native communities, older generations teach younger generations about their duty to protect the land. Without the land, there is nothing. Generations of Indigenous peoples have always taken up the fight for land, and while #NoDAPL may just be the latest chapter in this story, it is leading to a different outcome. Standing Rock is more than a community attempting to protect its water it is about Indigenous communities coming together. This is what Standing Rock is showing the world: Water. Is. Life.

The fight to protect the water around Standing Rock is an issue of environmental justice. The Dakota Access Pipeline was originally routed to cross the Missouri River just north of Bismarck, North Dakota—a city that is over ninety percent white. When Bismarck residents objected to their water supply being endangered by a potential oil spill, the pipeline’s river crossing was rerouted south onto land stolen from the Standing Rock Sioux in 1958.

This ostensibly localized struggle for justice is one that impacts all inhabitants of planet Earth, no matter their distance from Standing Rock. According to a recent report from Oil Change International, potential carbon emissions from the world’s existing oil, gas, and coal fields and mines stand ot take us beyond the 2° C of warming set as the allowable limit by the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris, to which the United States agreed. Thus, any effort to build new fossil-fuel extraction and transportation infrastructure is an implicit violation of the Paris agreements. The fight against fossil fuels is a fight for our planet, for justice, and for a livable future. Standing Rock is standing for the planet, and we must stand with them.

Native peoples in the Americas understand the universe as alive and sentient. All phenomena are understood to be a distinct expression of life force, or spirit. Since all persons—the human and the other-than-human, such as plants, animals, rivers, winds, and mountains—are expressions of spirit, they are recognized as interconnected and contingent. They are relatives. The people seek to honor life force through prayer and ceremony because it has given them life and continues to secure their survival. This field of connectedness, often referred to as the spirit world, responds dialectically to minute (and concentrated) propitiations by the people in order to effect change on their behalf. In turn, the people act as stewards of the land by protecting and nurturing the life force within it. Oceti Sakowin’s opposition to the DAPL has centered on the creation of the Standing Rock Sacred Stone Camp, or Spirit Camp, because the lands in question are historically sacred but also because ceremony is being conducted there every day. At its heart, the camp’s fight to protect the water is about ensuring the future life and well-being of Native and non-Native people and of the land. It is a decolonial assertion of stewardship. The gathering at the camp collectively honors this sacred duty. In ceremony, their power coalesces. They sing, they dance, and they pray this protection into being.

Capitalism is the excuse made to normalize settler colonialism as the theft of land and labor sustains the myth of progress. This foundational violence of U.S. Empire is repeating in Standing Rock today. Within the history of U.S. Empire, the question of racialization—how anyone came to be white or black or brown—is implicated in Native dispossession. This is why the #BlackLivesMatter movement has pledged solidarity with Standing Rock, underscoring that the struggles for Black emancipation must go hand in hand with the struggles for Native sovereignty, connecting the DAPL to the criminal pollution of water in Flint, Michigan. In the face of ongoing and regime-made environmental disasters, this gesture of anticolonial solidarity reveals that colonial power authorizes newer rounds of segregation, devaluation, and expendability.

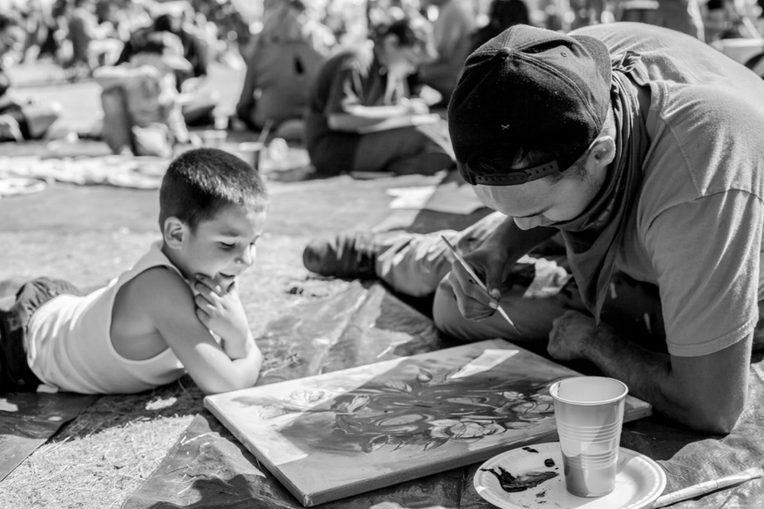

Just as the mediated images from #BlackLivesMatter have propelled both the movement and its detractors, images of Indigenous agency and solidarity are flowing from Standing Rock, providing an archive of source documents for histories of our present. The colonial gaze prepares for settler colonialism, securing its future through claims that the Indian has vanished. Live media of Indigenous agency is thus crucial to the writing of anticolonial history from the viewpoint of those who are risking their lives to be and remain anticolonial in the wake of state and corporate terror.

As our remarks unfolded in real time at the teach-in, they not only brought to light shared passions, but also the multiple sites of mobilization around water and all of the ways in which it gives life. Thus, we consider this teach-in to be more than a one-off event. Rather, it is a structure around which to strengthen relations and plan continued engagement. Our circle has been widened.

The order in which the authors of this essay are listed reflects the alphabetical order of their last names, and does not indicate the relative priority of any one author’s voice.

Natalie Avalos is an ethnographer of religion whose research and teaching focus on Native American and Indigenous religions in diaspora, healing historical trauma, decolonization, and social justice. She received her PhD in Religious Studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara and is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at Connecticut College. She is a Chicana of Nahua/Apache descent, born and raised in the Bay Area.

Sandy Grande is Professor of Education and Director of the Center for the Comparative Study of Race and Ethnicity at Connecticut College. Her research interfaces critical Indigenous theories with the concerns of education.

Jason Mancini is Director of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, Adjunct Professor of Anthropology at the University of Connecticut, and Visiting Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Connecticut College.

Rijuta Mehta is Assistant Professor of English at Connecticut College. Her teaching and research interests include theory and history of photography, postcolonial literatures in English, South Asian visual culture, South Asian feminisms, cultural and social critique, and regional literatures in translation.

Michelle Neely is Assistant Professor of English at Connecticut College. Her research and teaching focuses on questions of nature, culture, and democracy in American literature before 1900.

Christopher Newell is Museum Education Supervisor at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. He also sings with the Mystic River Singers, performing at powwows across the United States.