The Border as War in Three Ecological Images

From the Series: Ecologies of War

From the Series: Ecologies of War

Located at the western terminus of the US-Mexico border, Tijuana is a dry, desert city, and for much of its short history it has depended on water from the Abelardo Rodríguez dam. When the rains come, though, they are fierce. Every year, the hills crumble in landslides. Houses collapse. On the flats, floods have been recurrent.

One winter night in 1980, amid torrential rains, officials ordered the dam’s floodgates opened to release the excess water that was quickly accumulating.[1] For a decade, the settlements that dotted the bed of the Tijuana River had stood in the way of an ambitious development project, aimed at transforming Tijuana into a properly modern city. The flood was, in effect, the last eviction. No warning was given. The water dragged some of the drowned all the way across the border into the United States (Valenzuela Arce 1991).

In 1980, local officials weaponized Tijuana’s disaster ecology against its poor. Such a violent mass eviction might happen anywhere in Mexico, but here it was bound up with the border. Again and again, newspapers and officials cited the shame of having a squatters’ settlement be the first sight to greet US visitors. They celebrated the settlements’ elimination in these same terms.

Taken up in Mexico, a censorious US gaze becomes literal aggression. But the aggression of the border was already literal: even then, its militarization was underway (Chaar-López 2019). As an instrument of slow war—US-Mexico relations not with diplomacy but with other means—the border recruits Mexican violences into itself, co-opting and transmogrifying them. As this dynamic developed historically, so did ecology’s role in it.

Pie de página is a very short film. The shot that sticks in my mind is this: a stick poking at a pinkish goo. The goo is in the earth—it is the earth. It sticks to the stick. It is what the earth has become when mixed with human remains boiled down in lye. “These hills are full of bodies,” a friend tells me, a little wildly. It is 2017.

The shot is from a disposal site revealed by the Pozolero, a man who in 2009 confessed to dissolving some 300 corpses.[2] Mexico’s War on Drug-Trafficking began with Felipe Calderón’s presidency in 2006, but the Pozolero was at this job for years before. The remaining goo, of course, does not permit individual identification. Instead, it transforms the very matter of Tijuana’s hills, permeating them with the putridity of violence.

Tijuana is naturally “hot” (caliente, full of dangerous illegal activity), it is said, because it is a border city and, thus, a strategic bottleneck for illegal goods. It is no surprise that Tijuana should have been the theater of one of the war’s first military operations. But Mexican drug trafficking was fairly low-stakes until the United States closed Florida as a gateway for Colombian cocaine in the 1980s (Andreas 2009). When the route shifted, the border became a central stage for the US War on Drugs.

Guerra (war) is not a term I heard often in Tijuana, but one man did use it to flip the dominant narrative: the War on Drug-Trafficking was, in fact, a war on Tijuana’s poor. A Vietnam veteran and US deportee, he meant it more literally than I grasped. Later, I heard limpia (cleansing) used, matter-of-factly, to describe the extrajudicial killing of petty criminals and drug users under Calderón.

When my friend speaks of the hills, she does not just have the Pozolero in mind. The corpses he processed are a synecdoche for all the other bodies dumped there, the by-product of violence as an operational resource for both organized crime and the state. As a result, one no longer sees the hills as they were. One sees a land filled and commingled with the toxic waste of war.

In Zamora, Michoacán, many people dislike trees. They seem to see not fresh leaves but a mass of garbage in potentia, waiting to fall to the ground to be swept up. “¡Grandes! ¡Feos!” (Big! Ugly!), a woman vituperated to her neighbor.

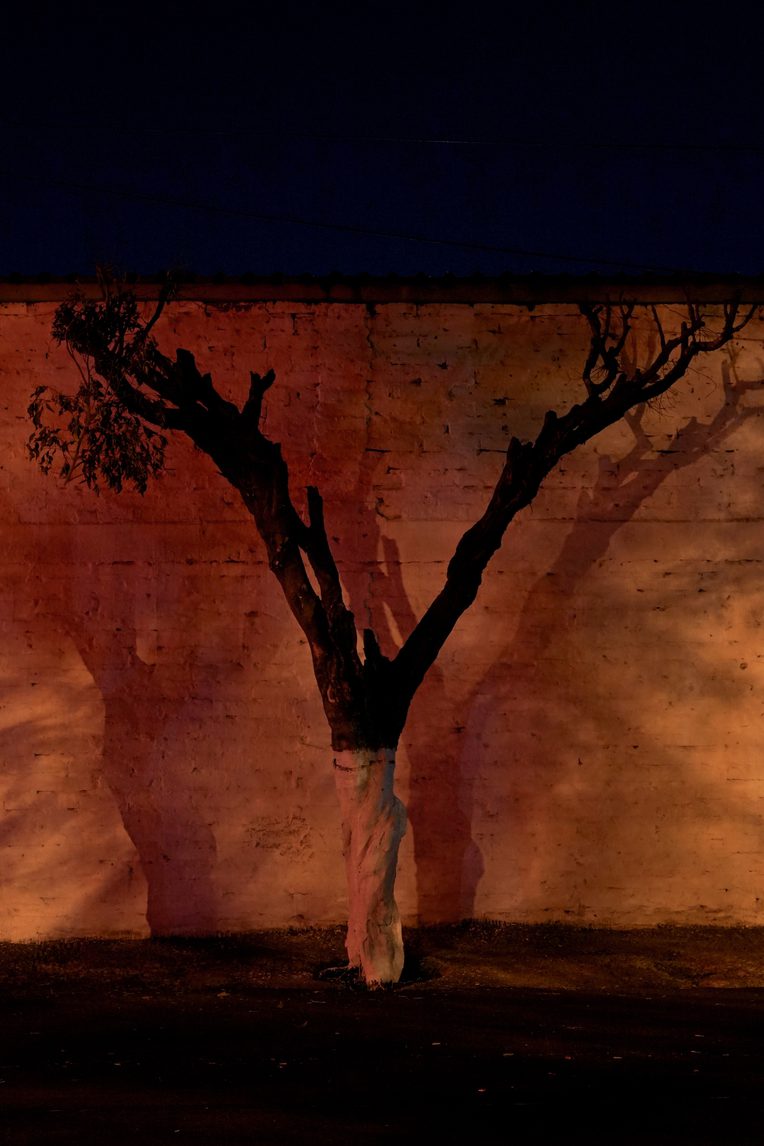

Michoacán was where the war’s military operations began, but Zamora was relatively calm when I moved there in 2010. In 2016, assassinations abruptly became a daily occurrence in this small city, placing it among the most violent municipalities in the country. In this context, the trees began to look downright sinister.

A hot dog vendor told me how two assassins waited for their victim among the trees. Even though the ones she meant were just a couple of scrawny ficus, for her they seemed to add a telling darkness to the scene. She went on to describe several killings in the vicinity, including one down a side street. Addicts hung out there, she told me, until several large trees were cut down. When I pressed her, she acknowledged military policing began about that time; however, she stuck to the trees as the main factor.

For this woman trees were metonymically linked with danger and crime. For a former taxi driver, they were killers themselves. He told me about a dead tree that fell on a car, killing the parents and orphaning their children in the backseat. “No tree taller than a person should be allowed!” he exclaimed. We spoke that day of murder, too, but he reserved his indignation for the trees.

Where those responsible for killing cannot be mentioned for fear of reprisals, trees can become a speakable locus of anxiety. As with the hills, ecological sight is transfigured: threatening trees are a phantasm produced by militarization and the ensuing fragmentation of sovereignty. As the wars that began at the border spilled south, Mexico as a whole has become one big border zone, and its ecological materiality bears witness to this change.

[1] For a chronicle of this episode, see Valenzuela Arce (1991).

[2] A pozolero makes pozole, a soup of lye-soaked corn.

Andreas, Peter. 2009. Border Games: Policing the U.S.-Mexico Divide. 2nd ed. Cornell Studies in Political Economy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Chaar-López, Iván. 2019. "Sensing Intruders: Race and the Automation of Border Control." American Quarterly 71 (2): 495–518.

Ovalle, Paola, and Alfonso Díaz Tovar. 2014. Pie de Página. Etno.mx; 2 veinte 22; Laboratorio de Análisis de Datos Visuales y Textuales, Instituto de Investigaciones Culturales, Museo Universidad Autónoma de Baja California.

Valenzuela Arce, José Manuel. 1991. Empapados de Sereno: El Movimiento Urbano Popular En Baja California (1928–1988). Tijuana: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.