The Invisible Mask: Kampo Pharmaceuticals and Chinese Medical Practitioners during the Coronavirus Crisis 2020 in Japan

From the Series: Responding to an Unfolding Pandemic: Asian Medicines and Covid-19

From the Series: Responding to an Unfolding Pandemic: Asian Medicines and Covid-19

“I am disappointed by the government recommending everyone just to wear masks and wash their hands. It would be more important to advise people on how to keep a healthy daily routine and how to make their immune system strong. Like through wearing the invisible mask of Ban Ran Kon, or taking other immune system–boosting kampo medicines,” says Ms. Kishikawa, the owner of a kampo pharmacy on a busy main road cutting across Nishi-jin, the old Kimono-weaving district of Kyoto. I am with Sayu, a friend, translator, and local resident who is connecting me to kampo practitioners in Kyoto. It’s March 2020. I have been intrigued by the quietness of kampo shops near our house, in contrast to social media accounts and news from within the People’s Republic of China (PRC) sharing information about the fruitful role Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is playing as part of an “integrated” approach to prevention and treatment for Covid-19 patients. Sayu herself is a longstanding user of kampo medicines, which in her and other Japanese acquaintances’ view includes TCM medicines. She is taking some extra these days, to keep herself and her daughter safe.

From where we sit, talking with Ms. Kishikawa at a low table, I see an advertisement for Ban Ran Kon herbal tea powder and lozenges. Mienai masku (“invisible mask”) stands in large letters above a Japanese-style drawing of an apron-wearing housewife, Ban Ran Kon lozenge in one hand, a blue and white packet of them in the other; the backdrop a white mask with little viruses depicted toppling over on both sides.

Alongside this image, Ban Ran Kon is described as safe for children and a “household medicine,” its effects both antibacterial and antiviral, including the alleviation of fevers and general “detoxification” (Japanese: gedoku 解毒; Chinese: jie du). Two panda bear mascots wash their paws, gargling what is presumably Ban Ran Kon tea. While in Japan the panda symbol appears in many China-related fields, here it signals ISKRA kampo pharmaceutical company and indicates to Kyoto residents that this is a kampo pharmacy as opposed to a biomedical one. Many kampo pharmacies look externally very similar to smaller biomedical pharmacies otherwise, and it is Ms. Kishikawa’s biomedical licence that allows her to sell kampo drugs. This bespeaks the increasing use of over-the-counter (OTC) kampo products in lieu of handcrafted personalized kampo medicines, and the closely-entwined development of kampo and “cosmopolitan” medicine for over a century (Lock 1980).

A face mask–wearing ISKRA panda greets us when we arrive at Sayu’s preferred pharmacy in a residential area of northern Kyoto. Locals call it a kampo pharmacy (kampo yakkyoku), although it brands itself as “Chinese Kampo Three-Star Pharmacy [中国漢方三ツ星薬局].” Sayu refers to the owner as her “Chinese doctor” rather than a kampo practitioner.1 Mr. Katsuyama is a Japanese TCM doctor, holding the relatively easy-to-obtain “International TCM Practitioner license” (class A; 国際中医専門員A) and running the pharmacy for over thirty years,2 after initially training as a biomedical MD and working in a conventional pharmaceutical company.

I interview Mr. Katsuyama while his wife serves customers. He explains that Covid-19 is not considered a new disease in TCM. Rather, it fits well into established disease categories within the Chinese medical canon: um byo (温病) or “warm diseases” (in TCM referred to as wenbing), specifically the sub-category, funetsu byo (風熱病) “heat-wind diseases” (in TCM, refeng yi, or “heat-wind epidemics”). Although he is careful not to say Chinese medicines are “effective” to treat coronavirus, he does suggest the relatively low death rate from Covid-19 in the PRC relates to the state-mandated use of TCM remedies in treating hospitalized patients.3 He recalls such treatments and also TCM-based protection measures in the PRC response to the SARS epidemic (2002/2003).4 Mr. Katsuyama does not know a single report of any hospitalized Covid-19 patient in Japan receiving kampo drugs or therapies, nor of any current clinical trials.

Mr. Katsuyama and Ms. Kishikawa are both cautious when talking with patients about kampo therapies for Covid-19, since kampo companies and associations warned practitioners against making claims about kampo’s effectiveness in this regard. This reflects long-standing legal restrictions on kampo, such as on the use of the terms “effective” (kiku 効く) and “efficacious” (koukateki 効果的). Hence ISKRA advertises products using the potent, culturally legible image of an “invisible mask” as a symbol for protection. These legal limitations create an uncomfortable double-bind for many kampo practitioners, who, active in various medical networks, have gained detailed information on materia medica and formulas used to treat Covid-19. The pharmacists I visited have however experienced stable or lower customer numbers during recent weeks owing to the broader legal context, fewer people going out and many online kampo purchases.

The practitioners I interview all highlight Japan’s reliance on China for raw ingredients of kampo drugs, more-or-less the case since Chinese medicine first arrived in Japan (sixth century CE). Although movements arose to rely on local Japanese materia medica,5 today most ready-made kampo products are again PRC-produced. Moreover, due to high local (PRC) demand for Covid-19-related therapies, several kampo

and TCM products have disappeared entirely from stock in Japan, and prices of others have increased.6

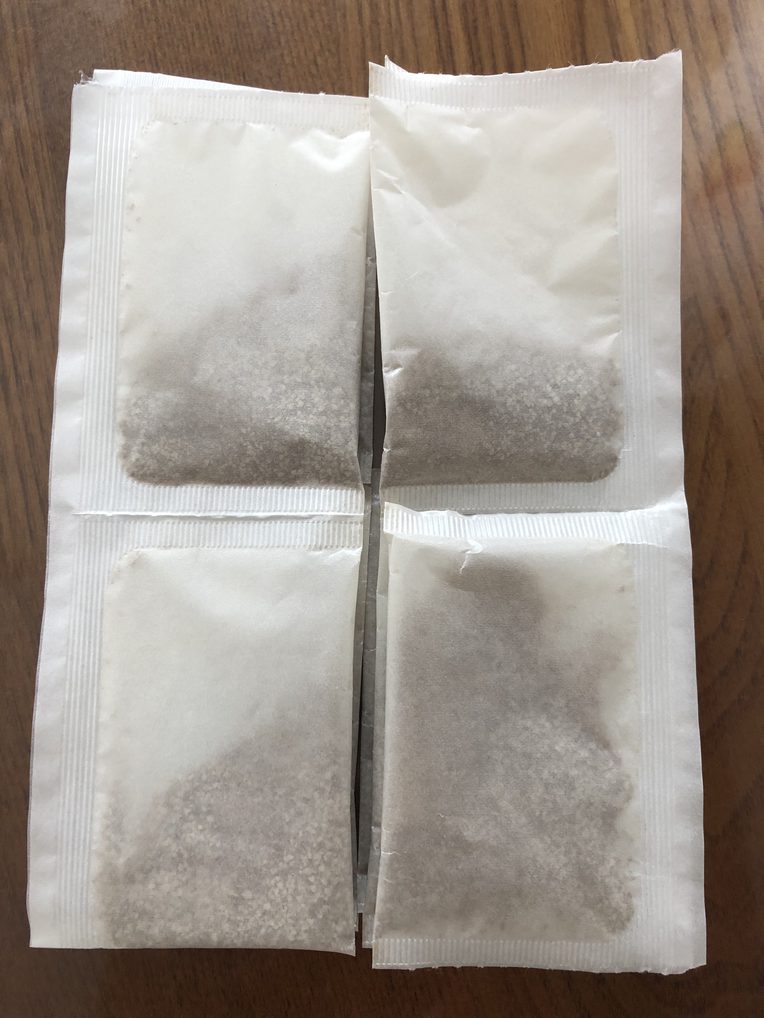

Meanwhile, kampo pharmacists who still prescribe and/or prepare personalized kampo compounds are hidden from view. In contrast to the above-mentioned treatments, such handcrafted kampo medicines (usually powders in sachets) are unlabeled. Customers tend to have long-standing relationships with such practitioners, paying higher prices despite the (legally) limited leeway for pharmacists to diverge from standard formulas.

When kampo is not meant to be considered efficacious and remains largely invisible, there are wide-ranging implications not just for kampo medicines, practitioners, and patients, but also for society at large. As this essay goes to publication, the number of people tested positive for Covid-19 in Japan is for the first time rising dramatically. Perhaps attention will turn again to kampo as individuals and society struggle to better understand and to heal the many effects of Covid-19.

Many thanks to the research participants, in particular Mr. and Ms. Katsuyama, Ms. Kishikawa, and Sayu, for their generosity in time and spirit. I am grateful to the editors of the series and to Gretchen de Soriano for commenting on earlier drafts. Special thanks furthermore to Junko and other patients willing to tell me about their experiences using kampo.

1. Kampo in Japanese literally refers to medicine of the “han,” pronounced as kan, i.e., medicine from the Han [漢] or “Han Chinese.” The term was initially used to differentiate local and Chinese medical knowledge from Portuguese and Dutch medical knowledge, which first arrived in Japan during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

2. The International TCM Practitioner licence is obtainable in

many countries outside of the PRC from organizations affiliated with

the Chinese government. Even though the licence Mr. Katsuyama holds

allows prescription and on-site production of kampo compounds, he and other TCM practitioners tend to rely mainly on ready-made pharmaceutical products.

3. Note, however, that the PRC’s official death toll from Covid-19 is likely to have been significantly underreported (see Campell and Gunia 2020; IANS 2020).

4. Marta E. Hanson (2010) describes these efforts in detail, including a host of clinical trials and expert reports after the SARS crisis was controlled; she analyzes how and why these have been conveniently “forgotten” by U.S. media and also seemingly by the WHO.

5. On this see, for example, the extensive work of Makoto Mayanagi and the on-line archive of Kampo history (mainly written in Japanese but with some articles with English summaries).

6. The ISKRA website

explains to readers their difficulty in supplying their best-selling

products due to the closure of its collaborating factory in China. At

the same time, they also attempt to allay any potential customer

concerns about contamination, stating that their other products are

entirely safe, and that “none of the workers (and their families) in

their Chinese collaborating companies had tested positive for corona.”

Campell, Charlie, and Amy Gunia. 2020. “China Says It's Beating Coronavirus. But Can We Believe Its Numbers?” TIME, April 1.

Hanson, Marta E. 2010. “Conceptual Blind Spots, Media Blindfolds: The Case of SARS and Traditional Chinese Medicine.” In Health and Hygiene in Chinese East Asia: Policies and Publics in the Long Twentieth Century, edited by Angela Ki Che Leung and Charlotte Furth, 228–54. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

IANS. 2020. “Coronavirus Casualties May Be Higher in China than Reported.” Telangana Today, March 23.

Lock, Margaret M. 1980. East Asian Medicine in Urban Japan: Varieties of Medical Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press.