After months of community opposition and protest, on March 7, 2013, the School District of Philadelphia’s School Reform Commission (SRC) voted to close twenty-three public schools and to merge or relocate five others (Herold 2013). An appointed governing board, the SRC,1 cited overarching budget constraints, facility disrepair, and a shrinking district school population due to the expansion of charter schools as justifications for this wave of school closures. Just over a month later, on April 18, the SRC voted to close an additional elementary school, bringing the total number of schools scheduled to close at the end of that school year to twenty-four (DeNardo 2013). These twenty-four schools, located almost entirely in low-income communities of color, amounted to about one in ten of every district-managed school in the city, and their closures displaced nearly ten thousand students (Gym 2013).

At the end of May in 2013, celebrated Philadelphia photographer Zoe Strauss put the word out to her network calling attention to the pending closure of these schools and requested assistance in photographing them in the few weeks that remained before they were permanently shuttered in June. This call marked the beginning of the online community group, the Philadelphia School Closing Photo Collective (hereafter the Collective). The individuals who responded to this call and participated in the Collective in other ways were everyday Philadelphians, among them professional and amateur photographers; artists, poets, and academics; public school students and their parents, teachers, and nurses; public school activists and advocates; and community organizers and independent media journalists. In just several weeks’ time, the Collective was created, grew, and got organized entirely through a Facebook group page. Its singular mission was to create a visual and public archive of schools slated for closure; there were otherwise no guidelines to shape the images Collective members captured. Gaining access to the closing schools in order to photograph their interiors and the spaces in use by the people who worked and learned in them was difficult. The initial posts on the Collective’s Facebook group page document the depth of consideration members gave to the issue of photographic consent and the lengths they went to secure it.

While only eighteen Collective members took and shared photographs of the closing schools, many more participated by using the group’s Facebook page as a type of informational bulletin board for local public education advocacy around a range of issues. We, the authors of this essay, are Collective members: two of us photographed three schools prior to their closure and all of us have photographed closed schools years after their closure. Together, Collective members photographed twenty of the twenty-four closing schools and took over fourteen hundred photographs, most of which were shared on social media and on a now-defunct webpage that members created to house their images. We spent two years locating and cataloging these photographs and we secured permission from each Collective photographer to donate this body of work to Temple University’s Urban Archives, where the photographs now reside with full public access.

Public Art, A Right to the City, and Archival Activism: The Work of the Collective

We understand the Collective—it’s origins and the initiative it undertook—through several distinct but related frameworks. The brainchild of Zoe Strauss, the Collective parallels some of her early public art projects creating accessible art experiences for people in her neighborhood. Using decaying spaces of her deindustrialized city as a canvas, these projects “explore[d] the everyday” amid what “mainstream media and city planners termed ‘blight’” (Uzwiak 2018, 21). These projects and her photographic work reflect Strauss’s attentiveness to “the displacement, violence, and resilience that mark contemporary urban (American) life, especially for poor and working-class people—histories often erased from official recollection as neighborhoods shift ownership via capital expansion or contraction” (Uzwiak 2018, 21). In inviting others to create a visual and public archive of schools slated for closure, Strauss enlisted others in looking at the very things she herself examines in her own photographic work while also creating a photographic archive to sustain a collective memory of these (once) public spaces. Regardless of the intent of each Collective photographer or their position on the closures themselves, photographing closing schools from the vantage point of those affected and making these images publicly available is an act of collective power and a claim for a public Right to the City (Lefebvre 1996; Harvey 2003, 2008). More than just an individual right of access to the urban resources that already exist, the Right to the City is a common right to change the city through the exercise of collective power and, in so doing, to change ourselves and create a “qualitatively different kind of urban sociality” (Harvey 2003, 939). If the coming together of disparate individuals to create a photographic archive documenting closing public schools can alter the urban experience, the Collective’s archive itself, Julia A. McWilliams (2017) argues, offers an opportunity to shape collective understanding of urban public schooling by not simply cataloging closed public schools but by offering avenues to contest hegemonic narratives used to justify public school closures. As archival activists have argued, archives become the basis for the validation of the stories that we tell ourselves—stories that build solidarity, group cohesion, and shared value systems—and produce what Andrew Flinn (2011) refers to as a “usable past,” one that can be leveraged to confront and transform injustices in society. The anthropological photo essay provides a platform for this social justice work.

The Marketization of Education and Racial Capitalism

Our analysis of the photographs in this anthropological photo essay draws from critical education scholarship and discourses on racial capitalism. Shaped by a market-centered “social imaginary” (Lipman 2011, 6), the marketization of education (Bartlett et al. 2002) is evidenced by policies such as high-stakes, standardized testing; school choice; divestment in public systems of education; and public school closures. Through these policies, longstanding educational inequities across racial/ethnic, language, and socioeconomic groups are individualized and framed as an “achievement gap” rather than an accumulated “education debt” owed to historically marginalized students that is historical, economic, sociopolitical, and moral in nature (Ladson-Billings 2006). Michelle Fine and Jessica Ruglis (2009) build off this analogy arguing for “a recognition of the thick racialized dialectics of ‘merit’ and ‘lack’ cultivated in public education” through market-based policies that “unleash and legitimate a perverse distribution of educational opportunities and deprivations onto racialized bodies” (Fine and Ruglis 2009, 20). Racial capitalism—an historical understanding of modern capitalism’s evolution whereby “racialism would inevitably permeate the social structures emergent from capitalism” (Robinson 2000, 2)—is a framework that “illuminates the social forces driving neoliberal education policies” (Lipman 2017, 5). Because “[capital] can only accumulate by producing and moving through relations of severe inequality among human groups . . . these antinomies of accumulation require loss, disposability, and the unequal differentiation of human value, and racism enshrines the inequalities that capitalism requires” (Melamed 2015, 77). Eve L. Ewing’s (2018) recent work on school closures in Chicago, for example, contrasts the framing of neighborhood schools as “failing” and “just bad schools” by educational technocrats and political pundits with neighborhood school communities’ furious responses to their impending closure. She argues that while neglect, racial segregation, and changes in federal and state housing policies paved the road to closure, the onus of “failure” was placed squarely on the communities attending these schools, in turn eliding the integral roles that these institutions have played in maintaining the social fabric of Chicago’s communities of color and a deep Black history that extends back to the Great Migration. The photographs selected for this photo essay take up the challenge of her ethnography for a discursive reorientation that focuses on the assets of these schools and their communities, the structural violence enacted throughout the closure process, and the devastation following closure.

“Picturing” Policy: Our Methodological Process and Positioning

Shortly after the closures, Collective members organized two gallery exhibitions of their photographs. However, opportunities for a more collaborative reading and interpretation (Lassiter 2001) of these visual texts with the photographers themselves and others exist as a potential to be realized. That the photographs are archived and publicly available through Temple University’s Urban Archives invites use by others to investigate, augment, and sustain discussions and develop new narratives about mass school closures that decenter official, and partial, discourses about our shared society (Hariman and Lucaites 2016). The participatory nature of the Collective’s work might be situated within scholarship on shared anthropology (Rouch 2003), collaborative ethnography (Lassiter 2000, 2001, 2005), and participatory visual and digital research (Gubrium and Harper 2013; Gubrium, Harper, and Otañez 2015)—each of which decenters a singular authoritative scholarly anthropological voice and centers collaborative sense-making and community knowledge. At its core, however, the Collective was not an ethnographic research project, though the photographs they produced can be analyzed as ethnographic texts, as we do in this photo essay.

As scholars of education and advocates for public schools, our read of the Collective’s images is informed by the theoretical framework we outline above, as well as our education-related work outside of the academy and the public and private spaces in which we have been educators and students ourselves. In cataloging the Collective’s photographs so they could be archived, we individually viewed all of the images produced and then collectively identified key themes across them. We each chose five photographs from the entire body of work that attracted us in either an aesthetic or conceptual way and together we aligned images to our thematic categories. Opportunities to talk with each photographer and understand the context behind each image taken have been limited to online interactions with those who responded to our inquiries. And at times we let our questions remain in our interpretive read of each image presented in the photo captions.

While several themes overlap, we have chosen to group the photographs into three major categories: before closure, during closure, and post-closure, to operationalize what Francesca Russello Ammon (2018) refers to as “picturing” policy processes as they unfold. In her work, she posits that photographs are a medium through which urban renewal practices and decisions can be captured and used to stimulate knowledge production and public conversation around their impacts. The photographs Collective members took memorialize the then soon-to-be closed public schools, in all their complexity. The images presented here explore a thematic gamut. We see in them the human cost of the closures, counter narratives challenging official and popular discourses that frame urban schools and the students of color they serve as deficient, the role of public schools in creating a Black middle class, accumulation by dispossession, public investment and divestment, and public schools as places of growth and quiet love. While the majority of photographs in this photo essay were taken by Collective photographers, we have also added several images of repurposed schools to sustain a conversation about how the state of public education for low income children of color can reveal much about shifting wealth and power relations in urban political economies. Given the concentration of the closures in overwhelmingly poor, historically Black neighborhoods, to whom these former public institutions once belonged documents how school closures reflect a racialized ceding of publicly owned assets to gentrifying entities like private developers. In this way, the images presented in this photo essay not only serve to memorialize the public schools that were closed, but also represents the next evolution of our work that seeks to render visible who benefits from their erasure.

Note

1. The SRC had governed the Philadelphia School District since 2001 when it was taken over by the state. After years of pressure by community groups and recent pressure from Philadelphia’s Mayor Kenney, the SRC voted to disband itself in November of 2017 and a locally elected school board resumed control of the city’s public schools in 2018 (Graham 2018).

Download “'This is about racism and greed': Photographs of Philadelphia’s Mass School Closures” by Amy J. Bach, Julia A. McWilliams, and Elaine Simon as a pdf booklet.

Photos

[It] is a place of quiet love.

—Debra Perry (as cited in Herold 2013)

Perry’s statement is in reference to Bayard Taylor Elementary School, where she was working as a kindergarten teacher for nearly three decades. This statement was given during the public comment period prior to the school closure vote by the SRC on March 7, 2013. In the end, her school was spared closure. However, Walter G. Smith Elementary was not offered the same fate. In the final weeks before closure, this image captures the intimacy between the subjects of this photo as reflected in their posture—leaning into a trust that binds them within the darkness of an emptying classroom. Framed by the light of the window, this image gestures to the hope and “quiet love” that emerges from the human moments between students and their educators in public schools. Ewing (2018) argues that these are the assets that often go overlooked in the “cost savings” and utilization audits that drive the narrative around school closure. Framed as “just bad schools,” the relationships between elders and children in historically Black schools are elided. This image of a student and his teacher, either after school hours or at lunch time, offers an important counter narrative, like Ewing, to framings of these schools as violent, decrepit, and “failing.” The classroom is well-kept, the floors are clean, there is light that is attempting to penetrate the darkness through the window. While disinvested, threatened by closure, and surely struggling with the problems that accompany serving families living in deep poverty, it still persists as a space of growth, guidance, and potential. As Ewing points out, these are the facets of public schools that communities have fought—through protest, hunger strikes, and grassroots organizing—so hard to preserve.

Three student portraits produced by Leidy Elementary’s students lean against a copy of da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, blocking most of the piece with the exception of her eyes that give an approving gaze to the genius rendered in front of her. The vibrancy of their portraits both eclipses the Mona Lisa and represents a resistance to the culture of high-stakes testing and accountability that shaped the road to school closures in Philadelphia. The students, in spite of the defunding of art curriculum in lieu of “testable” skills, continued to produce through murals, mosaic making, and art, filling their schools with color and making a mark on these buildings. Leigh Patel (2016, 400) writes that within oppressive social structures, “education has the potential to serve and shield spaces of unruly learning.” Such “unruly learning” here manifests in the lack of prescription across the portraits, as each of the students that produced the work embraces elements of shading, highlighting, and color selection in diverse and brilliant ways. Creativity, effervescence, and Black artistic potential are traded in this framing for a focus on academic deficiency, scarcity, and dysfunction.

In this image we see several faces from the ninety-ninth and last graduating class, the Class of 2013, during their “Great Walk,” a tradition where graduating seniors walked the perimeter of the school to bid farewell (Bach 2016). Erected in 1914, Germantown High School served not only the expanding Germantown section of Northwest Philadelphia but communities along the Route 23 trolley line including Olney, Ogontz, Tioga, Mount Airy, and Chestnut Hill. Once home to a large German community, the neighborhood became African American following the white flight of the mid-twentieth century. While its struggles mirrored those of neighborhoods thrust into the tumult of urban change and race relations in the latter half of the twentieth century, for the flourishing part of its history the school represented a catalyst for white and Black middle-class mobility as well as a community anchor and mainstay in a historically Black neighborhood. There is hope and promise in the colors of the students’ robes as well as the green and white balloons ascending upward. The composition of the image indicates movement as the arms reach upward, a symbol of the aspiration of the graduating students. The students’ faces are joyful, looking skyward to auspicious futures. While the image lifts, it is also melancholy, as the black balloons foreshadow the death of a tradition that has existed for the last century. As the students stand in a circle, the familial nature of relations contrast with the building behind them, a school that has weathered budget crises, disinvestment, and population decline for the last thirty years, going from a school of three thousand students at its peak, to less than seven hundred by 2013. The students are looking above to both pay homage to the ancestral legacy of Germantown, but also to bid farewell.

The vantage point from which this photograph was taken communicates a sense of grandeur and importance of this building, a public school. Of the twenty-four public schools closed in 2013, half were on the National Register of Historic Places. Created after the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which was a response to the mid-twentieth century development and demolition “when federal highway and infrastructure projects and urban renewal significantly impacted or destroyed many historic neighborhoods in the nation’s oldest communities” (Kergesie 2017), the National Register identifies in order to preserve buildings of cultural, historic, and architectural importance. The image is filled with light, as sunshine streams through the stained glass windows. The marble walls also reflect the light, illuminating the contrasting metal detector below. While the space reflects the lofty goals of public education when this building was raised, the metal detector nods to the criminalization of the predominant population in the school, African American youth, that came to represent a majority in the latter half of the twentieth century. The photograph is paradoxical: the design of the building with its high ceilings, grand staircase, and stained glass windows mark those who use the space as important, however the newer addition of a metal detector reduces the young people attending Vaux to deviants, unworthy of moving about the space freely.

The eye is drawn to the containers collecting rainwater pooling from the ceiling and the forlorn mop that forms a temporary barrier across the hallway. There is a normalcy to the image as students walk around the sopping newspapers, a regular fixture of the landscape in a deteriorating building. Framing the containers are faded inspirational quotes (“Failure is not the worst thing in the world, the very worst is not to try.”) as well as older posters that struggle to hold onto the walls. The space is dark, as indicated by the use of the camera’s flash, with little natural light. The composition of the image is heavy and severe, with little color beyond the red lockers. The space is still functional, as the broken locks on the lockers have been replaced by hanging locks, yet there is also an exhaustion to the effort, as our eyes circle back to the dripping rainwater and the tide of corrosion that overwhelms the space. The image is ultimately a commentary on austerity and the human spirit as children and their educators fade into the background, attempting to save a space that cannot keep up with the elements. One cannot help but see a corpse on life support here, efforts to sustain it thwarted by the inevitability of its end. Pepper Middle School was closed with twenty-three other schools in June 2013 and now sits vacant on a flood plain, awaiting demolition.

The young man at the center of this image looks with calm certainty at the camera holding a sign with a succinct message about the school closures as simple and functional as the repurposed cardboard and black marker used to make it. He has come to the school district building to protest the pending school closures. He wears a t-shirt from Germantown High School, a school celebrating ninety-nine years of service to its predominantly African American community while also preparing for its potential closure, a decision that would be handed down with the SRC’s vote on this day. The twenty-four schools that were closed displaced young people from their neighborhoods, sending them to schools that mostly performed no better than their shuttered ones (Jack and Sludden 2013; Research for Action 2013), and created “education deserts” in high-need city neighborhoods (Simon 2013). Philadelphia educates the vast majority of Pennsylvania’s poor and high-needs students without the sufficient financial resources required to do so (Jablow 2015). Rather than tax the state’s growing natural gas industry, then-Governor Tom Corbett chose to cut more than $860 million from public education in the 2011 budget (Denvir 2014). Since 2011, Philadelphia absorbed 35 percent of statewide funding cuts even though it educates only 12 percent of the commonwealth’s children (Ward 2014). Overall, these cuts reduced Philadelphia’s per-pupil funding by over $1,300 per student in a district that already spends far less per student than many of the wealthier, and whiter, surrounding suburbs. Historian Tom Sugrue (as cited in Denvir 2013) explains: “Philadelphia, like most big urban school districts, has long depended on state and federal funding, both of which are subject to the vagaries of partisan politics, anti-urban sentiment and austerity . . . essentially, our education policy amounts to segregating minority and high-poverty students in struggling school districts, starving school budgets, experimenting in various untested forms of school governance and then blaming teachers and students when the schools fail.”

Several Collective photographers were able to negotiate entry into schools and were given permission to take photographs of the teachers, students, and staff members going about their daily business of teaching, learning, and working. These photographs map faces onto the closures and reveal the human element of education overlooked in the current educational context where high-stakes, standardized test scores serve as proxies for quality and meaning. In this image, the principal of Fairhill Elementary School sheds tears over its pending closure. Overcome with emotion, she crouches down in a dimly lit hallway of her school, the take-out coffee at her feet an energy source to propel her through a long day at the helm of her school. The cinderblock wall against which she leans and linoleum flooring, inexpensive construction materials, are kept clean. The mural to the left, silhouetted bodies in motion, is a colorful and lively addition to what is otherwise a somewhat drab space. This school is and has been cared for by the people who work and learn in it.

The photographer’s decision to anonymize the individuals in these images draws the viewer’s eye to the text on the bodies of these headless figures—text which becomes the subject of the images and that offers cynical perspectives on the school closures by the very people affected by them. In this school in the process of closing, the individual in the image on the left wears a repurposed sign intended to mark materials to be thrown away clipped to their lanyard. Substituting one’s school identification card for a sign reading “School District of Philadelphia—Trash” may be an expression of disdain for the school district’s disregard for its human capital as well as an expression of stigma and shame. This individual shows the photographer they are being discarded along with the school. Teacher layoffs attributable to the 2013 closures are difficult to determine, as the closures were followed by what Philadelphians called a “doomsday budget” that was approved by the SRC for the 2013–2014 school year, which laid off nearly 3,783 employees including 676 teachers, 283 counselors, all 127 assistant principals, 1,202 aides, school nursing positions, and left no funding for basic supplies such as books and paper (Erb 2013; Gabriel 2013; Strauss 2013). Some of these positions and monies for resources were ultimately restored when the federal government released $45 million in aid but not until after it was held hostage by then-Governor Corbett on conditional concessions from the teacher’s union. When a sixth grade student suffered an apparent asthma attack at a school with no nurse on duty and later died, the governor released the funds (Denvir 2014).

In the image on the right, an individual wears a Bok High School class of 2013 t-shirt and a backpack. Likely a student from the school, the t-shirt showcases a senior bravado that is both celebratory of the achievement of graduation and unsentimental in its recognition of the finality of Bok High School, offering an additional narrative about the closures from the perspective of students. The explosion depicted is presumably a bomb being dropped on the school. The school is closing, yet the t-shirt of the very last graduating class of this historic high school seems to revel in its complete erasure.

This image of a school mural in progress started just days before the end of the life of a school shows beautiful defiance in the face of the school closures. The art teacher in this image, set to be laid off at the end of the week this photograph was taken, included all the students of the school in making this mural. The vibrant colors and outline of the yet-to-be-painted word “Soulful” convey a positive message of hope, potential, and strength. The circular forms with students’ handprints on an exterior wall of the school are a public show of connectedness—between the students themselves and the students and their school. Calling each student individually to mark their handprint on the mural, the art teacher told each one as they pressed their painted palms to the brick of their school, “You were here.”

Photographs by the Collective document the massive logistical and physical work involved in closing twenty-four schools and reallocating their resources, both human and material, to other places or disposing of them. Photographs of boxes filling entire school gymnasiums, piles of discarded equipment and supplies, and overflowing school dumpsters filled with books and curricular materials raise questions about official narratives justifying the closures for reasons of efficiency and financial savings. In this uncomfortable image, young children are involved in the strenuous work of moving their own school while it is still in session. Students carry plastic crates packed full with books, papers, and other materials down the school steps and out the door. The posture of one young boy mid-stair shows the weight of the crate he carries. In enlisting its children to pack up and move their own classroom materials, rather than use them for learning until the last day of school, we read in this image a surrender, a school that has given up under the weight of an inequitable school system.

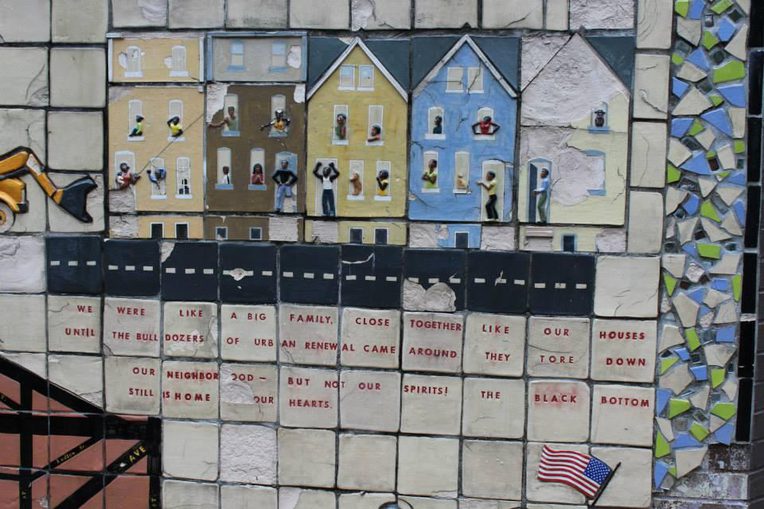

From its inception, University City High School (UCHS) was a controversial project. Part of the early 1970s Science Center development between 34th St. and 40th St. and Market St., planners envisioned UCHS as “the” science magnet school that would serve the children of both the neighborhood and the Science Center and the University of Pennsylvania’s employees’ children. However, in order to make way for the building of the Science Center, a historically tight-knit African American community known as “Black Bottom” was razed. This image, a student-produced mosaic at the main entrance to the high school commemorating this neighborhood, gestures to the deleterious impact that mid-twentieth century urban renewal policies had on poor Black communities in Philadelphia. Unfortunately, UCHS never realized its potential, becoming a heavily segregated school that was labeled “failing” and slated for closure with the twenty-three other neighborhood schools throughout the city. Its consequent demolition reminds us of the erasure of communities like Black Bottom, as the artwork that children left to memorialize the community have also been reduced to rubble. The demolition of UCHS also offers additional evidence for what Lawrence J. Vale (2013) terms “twice-cleared communities,” or communities labeled as blighted and subsequently razed in order to build newer and more modern public housing, and then, in turn, similarly labeled and razed again. Drexel University has purchased the vacant lots where the school used to stand and is partnering with a private company to build a mixed-use development to include residential, commercial, and educational facilities. Whereas the first round of urban renewal preserved a public commitment to education in the form of UCHS, Elaine Simon (2013) draws a comparison between this wave of public school closures and the failed “urban renewal” policies of the recent past, which similarly decimated urban neighborhoods and displaced low-income residents of color without any direct benefit to them.

This rendering documents the future of a twice-cleared community. Currently in pre-development, uCity Square will sit on the site of the now-demolished University City High School, which was itself built on the site of the razed African American community, Black Bottom. The imagined use of this future space depicted in this rendering shows who belongs in this development, and who does not. Professional people on cell phones with to-go coffee cups walk in business attire. A woman in a head scarf walks towards the sleek buildings in the background that catch the light of the sun. A man of color pushes a stroller in a sleeveless white t-shirt, clothing that contrasts with the professional attire and collegiate clothing worn by many of the other figures. The wide walkways and plaza in the background prioritize pedestrian over vehicular traffic. An expensive-looking modern car is stopped next to a cyclist in a brightly painted bike lane, both yielding to pedestrians crossing the street without any traffic light or sign instructing them to do so. The white trail of an airplane shoots upward toward the heavens in the sky. This is progress. This is the future (and it is bright). The predominantly working class and poor African American community that once used this site for residence and schooling are nowhere in sight.

Julia de Burgos Magnet Middle School was originally one of the oldest high schools in Philadelphia, founded in 1890 as the Northeast Manual Training School. Designed by Lloyd Titus, the school was intended to provide vocational training to poor and working-class boys in the industrial trades. The school’s subsequent transition to Thomas Edison High School in the late 1950s offers a window into changing demographics as white residents fled the city. The school, becoming heavily segregated and neglected, by the 1990s was infested with rats and named the “worst high school in Philadelphia.” By 2001, the district leased the school to private management through Edison Inc. The school was closed in 2002 and left vacant until a fire claimed the property in August 2011. Purchased by Orens Brothers and Mosaic Development Partners in 2013, the school was demolished and the lot used for the building of a shopping center. The vantage point from which this photo is taken shows this building to be a massive, hulking presence in the neighborhood it occupies. The discarded tires on the front step, the graffiti as high as an individual can reach, the caved-in roof are all indications this vacant school was most likely a nuisance to its surrounding community in the years since it was closed and left to rot. We read in this image a community so devalued in the eyes of the city that it did not receive protection from a derelict space, and a city with so little regard for the building itself that it did not bother to find an avenue for reuse. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, this once-grand public school, now demolished, documents the changed nature of investment in public education and serves as a bellwether for more recently closed schools in neighborhoods less desirable to developers.

The Public Works Administration (WPA) erected Bok Technical High School in 1938 as a vocational high school to prepare students for careers in the trades and culinary arts. Its limestone yellow brick looms over blocks of South Philadelphia row homes, an impressive 340,000 square foot property in the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of “East Passyunk.” After its closure the school was sold for $1.75 million to developer Lindsey Scannapieco who began transforming the eight-story building into a commercial space for local businesses. As the neighborhood newspaper, the Passyunk Post, announced, “you can get your haircut at Fringe Salon, drink some beers on the rooftop, get in a workout at a boxing gym, send your child to preschool and plenty more” (Farnsworth 2016). Philadelphia’s twenty and thirty-somethings have flocked to Le Bok Fin, the new rooftop bar that uses the former culinary training facility to prepare $6 “Paris” hot dogs, $8 baguettes, and $12 charcuterie plates as part of its pop-up French menu. Spaces in this former school are also available to rent out for weddings. The site has become a site of fierce contest between old time residents of the formerly working-class periphery of the school and “New Philadelphians,” a term used to describe the recent influx of young residents that enjoy bike lanes, high-end craft beer, and exposed brick walls in their living rooms. “New Philadelphians” commend developers like Scannapieco for preserving historic buildings like Bok Tech by repurposing them for commercial use while critics underscore that the working-class communities of color who once benefited from the social mobility that a public vocational education provided are the last to access and benefit from the space in its current form.

In this image, the wedding party in colorful bridesmaid dresses on the rooftop of this former school are much brighter than their surroundings. They are a splash of individual possibility and promise, against a grim (public) background of the city. In wearing sunglasses, these white women are blind or indifferent to the school on which they stand. They victoriously claim this once-public space for their private party.

Conversations in Philadelphia around who benefits from school closures and their subsequent redevelopment echo scholarly concerns with the shifting relationship between urban space and the new economy. Critical scholars like Pauline Lipman (2011) have likened closures and their repurposing to David Harvey’s (2007) notion of “accumulation by dispossession,” where capital and power become concentrated in the hands of the wealthy at the expense of the public. In cities this has meant the privatization of formerly public spaces, institutions, and services, depriving poor communities of color of their Right to the City (Harvey 2012). This image catalogues the recent redevelopment of one of the twenty-four closed schools in 2013, Abigail Vare Elementary School in the Pennsport neighborhood of South Philadelphia, into luxury townhomes (i.e., “Abby Row”). Several remaining elementary schools near the former school have reported overcrowding in recent years, all serving predominantly working class Latino, African American, and white children. In spite of this crowding, the sale of the building precludes the district from reopening the school, therefore bringing into relief the impossible reclamation of former public institutions once they are privatized.

References

Ammon, Francesca Russello. 2018. “Picturing Preservation and Renewal: Photographs as Planning Knowledge in Society Hill, Philadelphia.” Journal of Planning Education and Research.

Bach, Amy J. 2016. “The Philadelphia School Closing Photo Collective: Photography as Documentation, Public Participation, and Community Resistance.” Streetnotes 25: 322–35.

Bartlett, Lesley, Marla Frederick, Thaddeus Gulbrandsen, and Enrique Murillo. 2002. “The Marketization of Education: Public Schools for Private Ends.” Anthropology and Education Quarterly 33, no. 1: 5–29.

DeNardo, Mike. 2013. “Philadelphia School Board Votes To Shut Down M. H. Stanton Elementary School.” CBS Philly (blog), April 19.

Denvir, Daniel. 2013. “Who’s (Still) Killing Philly Public Schools?” CityPaper, May 22.

———. 2014. “How to Destroy a Public-School System.” The Nation, September 24.

Erb, Kelly Phillips. 2013. “Did School Layoffs; Budget Cuts Contribute To Girl’s Death?” Forbes, October 11.

Ewing, Eve L. 2018. Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Farnsworth, Taylor. 2016. “You Can Now Get Married at South Philly’s Most Talked about Former School.” Passyunk Post (blog), August 16.

Fine, Michelle, and Jessica Ruglis. 2009. “Circuits and Consequences of Dispossession: The Racialized Realignment of the Public Sphere for U.S. Youth.” Transforming Anthropology 17, no. 1: 20–33.

Flinn, Andrew. 2011. “Archival Activism: Independent and Community-led Archives, Radical Public History and the Heritage Professions.” InterActions 7, no. 2.

Gabriel, Trip. 2013. “Budget Cuts Reach Bone for Philadelphia Schools.” New York Times, June 16.

Graham, Kristen A. 2018. “Local Control Is Here: New Philly School Board Holds First-Ever Meeting.” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 9.

Gubrium, Aline, and Krista Harper. 2013. Participatory Visual and Digital Methods. Walnut Creek, Calif.: Left Coast Press.

Gubrium, Aline, Krista Harper, and Marty Otañez, eds. 2013. Participatory Visual and Digital Research in Action. Walnut Creek, Calif.: Left Coast Press.

Gym, Helen. 2013. “School Closures Rock Philadelphia.” Rethinking Schools 27, no. 4.

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. 2016. The Public Image: Photography and Civic Spectatorship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Harvey, David. 2003. “The Right to the City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27, no. 4: 939–41.

———. 2007. “Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 610, no. 1: 21–44.

———. 2008. “The Right to the City.” New Left Review 53: 23–40.

———. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. New York: Verso.

Herold, Benjamin. 2013. “SRC Votes to Close 23 Schools, Spares 4.” Philadelphia Public School Notebook (blog), March 8.

Jablow, Paul. 2015. “When It Comes to Education Funding, What’s the Deal with Philly Schools?” WHYY(blog), June 17.

Jack, James, and John Sludden. 2013. “School Closings in Philadelphia.” Perspectives in Urban Education 10, no. 1.

Kergesie, Cory. 2017. “National Register of Historic Places (Sites).” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 2006. “From the Achievement Gap to the Education Debt: Understanding Achievement in U.S. Schools.” Educational Researcher 35, no. 7: 3–12.

Lassiter, Luke Eric. 2000. “Authoritative Texts, Collaborative Ethnography, and Native American Studies.” American Indian Quarterly, 24, no. 4: 601–14.

———. 2001. “From ‘Reading Over the Shoulder of Natives’ to ‘Reading Alongside Natives,’ Literally: Toward a Collaborative and Reciprocal Ethnography.” Journal of Anthropological Research 57, no. 2: 137–49.

———. 2005. “Collaborative Ethnography and Public Anthropology.” Current Anthropology 46, no. 1: 83–106.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1996. “Right to the City.” In Writings on Cities, 63–181. Translated and edited by Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lipman, Pauline. 2011. The New Political Economy of Urban Education: Neoliberalism, Race, and the Right to the City. The Critical Social Thought Series. New York: Routledge.

———. 2017. “The Landscape of Education ‘Reform’ in Chicago: Neoliberalism Meets a Grassroots Movement.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 25, no. 54: 1–28.

McWilliams, Julia A. 2017. “Collective Memory and ‘Remembering’ School Choice: The Role of Archival Activism.” Paper presented at the American Anthropological Association Annual Meeting, Washington, D.C., November 29–December 3.

Melamed, Jodi. 2015. “Racial Capitalism.” Critical Ethnic Studies 1, no. 1: 76–85.

Patel, Leigh. 2016. “Pedagogies of Resistance and Survivance: Learning as Marronage.” Equity and Excellence in Education 49, no. 4: 397–401.

Research for Action. 2013. “School District of Philadelphia School Closings: An Analysis of Student Achievement.” Philadelphia: Research for Action.

Robinson, Cedric J. 2000. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Rouch, Jean. 2003. Ciné-Ethnography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Simon, Elaine. 2013. “Are School Closings the New Urban Renewal?” Philadelphia Public School Notebook (blog), March 4.

Strauss, Valerie. 2013. “Philadelphia School District Laying off 3,783 Employees.” Washington Post, June 8.

Uzwiak, Beth A. 2018. “Make of This Whatever You Want: Violence and Intimacy in Zoe Strauss’s I-95 Project.” Photography and Culture 11, no. 1: 19–39.

Vale, Lawrence J. 2013. Purging the Poorest: Public Housing and the Design Politics of Twice-Cleared Communities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ward, Sharon. 2014. “A Strong State Commitment to Public Education, A Must Have for Pennsylvania’s Children.” Pennsylvania Budget and Policy Center (blog), April 30.