This War Has Become a Part of Us

From the Series: Russia’s War in Ukraine, Continued

From the Series: Russia’s War in Ukraine, Continued

It is often difficult for me to find the right words to describe the situation when there is no war. And now, on the eighteenth day of the war, as I write this, finding the right words seems utterly impossible. There are only feelings, emotions, and affects left. Like this unrelenting feeling of nausea that has been pulsating in my stomach and my chest since I woke up on February 24. It doesn’t release its grip on me. I don’t know if it ever will. I am scared. I cry often. I hate. I have never been so vindictive and bloodthirsty. I have never been so afraid and felt so helpless.

Yet, I have also never been so busy. Today I have to coordinate the delivery of medical kits to my friends in the territorial defense forces. I have to find a place to stay for a couple of people fleeing the war, translate for a journalist, and do a hundred other things that will come my way that I don’t know about yet. Every day is like that now.

This war has brought out the best in us. We organize, we support, we put on hold the grudges we held before. We hug more, we care more deeply, and smile more sincerely. We muster the courage, we offer more help, we share more, and share more readily. We offer our bodies, our spirits, and our skills for the common cause. We do all this all the while feeling guilty for not doing enough.

Dima (a pseudonym) is now weaving masking nets for the military. Dima has an opioid use disorder. He has been taking buprenorphine for over a decade. He also spent a few years in various prisons: he was sentenced a couple of times for drug possession and dealing before he joined a medication-assisted treatment program for opioid use disorder. He jokes that his prison time comes in handy now. “I learned to make masking nets there.”

For a couple of years now, Dima has had a part-time job as a social worker in a harm-reduction program that distributes syringes, needles, and alcohol pads to people who inject drugs. He also spends a couple of hours every day at the office weaving masking nets. His clients and friends come to join him. They bring whatever material supplies they can find so the masking nets come about faster and better. Dima and his friends all speak Russian. When I call Dima to ask if he needs any help, he tells me in Russian that some dark-colored cloth would be nice. He adds in Ukrainian, “Everything will be Ukraine.” This is a short-and-sweet version of the sentiment, “Ukraine will win and everything will be fine.”

This war has also brought out the worst in us. We fear and hate. We cry for our homes that have been destroyed and for our friends who have been killed. We don’t choose words anymore. We have become impatient and rude. We are quick to jump to conclusions. We have become more suspicious, distrustful, and cynical. We judge and discriminate. Inadvertently or unwittingly, we put each other in harm’s way.

The war has revived and strengthened patriarchal stereotypes and roles: Men-as-protectors and women-as-nourishers. Men between the ages of eighteen and sixty cannot leave the country, as they may be conscripted. They cannot leave even though the viis’kommaty (military district offices) are overwhelmed.

My husband met Zakhar (a pseudonym) in a never-ending line in a viis’kommat in X city in Western Ukraine. Zakhar fled Kharkiv together with his wife and their child. Their home has been destroyed. But when the family arrived in X, they had to separate. Many local people and organizations do not want to host men. Zakhar’s wife and child were taken in and found a new home. But Zakhar sleeps in a railway station now. It is a no-win situation: he won’t be conscripted any time soon and he won’t easily find a place to stay. Displaced from his home by Russian forces, he is made homeless by his fellow Ukrainians.

The billboard near a railway station in X reflects and reinforces this sentiment about internally displaced men. It openly calls on displaced men who came to X to “Go back! Protect your home and your country!” As if those who live in X have a lesser responsibility to protect their country. As if it is somehow Zakhar’s fault that he happened to live closer to the aggressor.

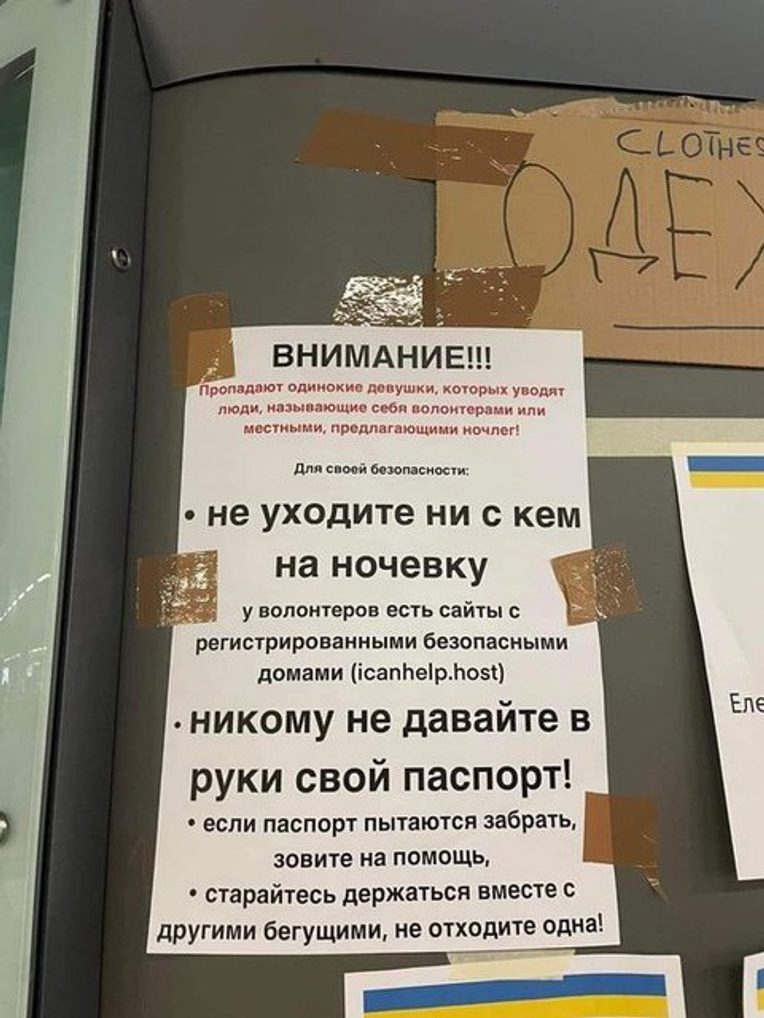

At the same time, there are reports about women traveling alone and women with kids who have disappeared from the railway and bus stations in Germany and Poland. “Do not give your passport to anyone!” The announcements in Russian and Ukrainian yell this information at the refugees as they arrive (see image below). Traffickers disguised as volunteers have already started to prey on exhausted and trusting women as they flee the war.

This war has divided families. It makes us feel helplessness and hatred. It also refines our survival instinct and our cooperative skills.

I started writing this piece on the fifteenth day of the war. I am finishing it on the nineteenth. Something always comes up and I never finish it. There is always something more important to do.

I don’t remember anymore what day or date it is today. I only know that today is day nineteen of the war. The war changes your perception and reckoning of time.

* * *

This text is patchy, incomplete, and fragmentary. But this is how everything feels right now. Unfinished, imperfect, shattered. I still cannot find the right words to describe it all. The feeling of nausea has become a part of me. As I finish this text, it is past midnight again. I still can’t find and still don’t care about the right words. The only thing I care about now is whether there will be another air raid siren tonight.