Trenches Equivalent: Waging Sri Lanka’s “War of Position”

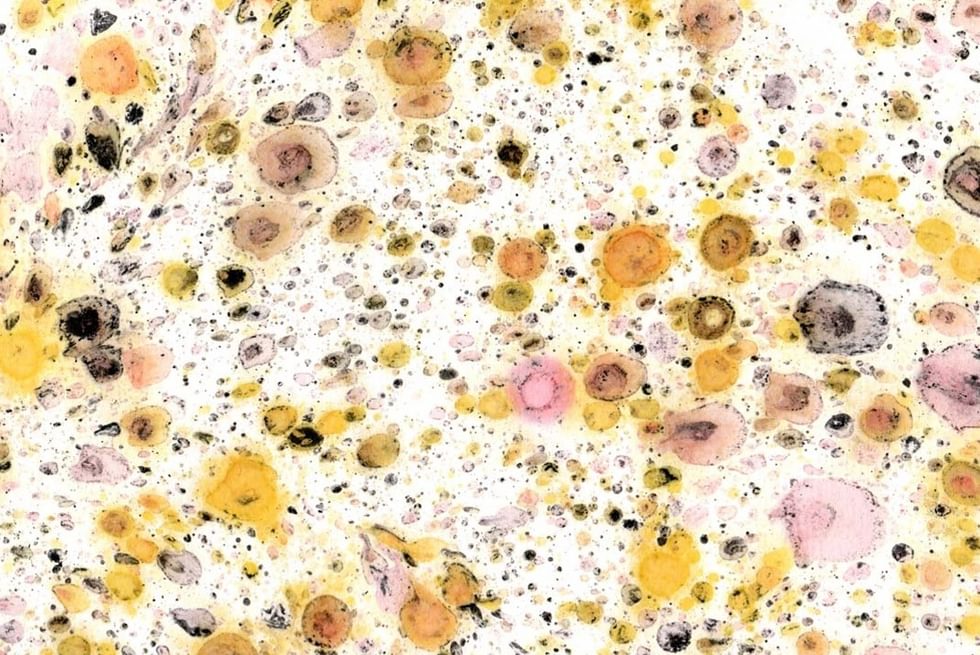

From the Series: Substitution

From the Series: Substitution

In 2018, I sat with Vijeyeletchumi, a Hill Country Tamil plucker in her tea estate line-room home. Lifting her skirt, she revealed a trail of four open wounds running from her toes to her calf: leech bites from Sri Lanka’s tea trenches.

She tore a shriveled, moistened piece of tobacco into two and covered the largest pink wound on her calf with one piece as an antiseptic and coagulant. Smearing light pink, slaked lime from a small packet onto a betel leaf, she placed the other piece on top of it. Folding the contents into a square, she placed it into her mouth and began to chew. The next morning, she took off work to walk to the estate clinic for medicine.

In December 2021, Sri Lanka signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Iran to settle a $251 million USD debt for outstanding payments on oil purchases from 2011. The MoU permitted the state-run Ceylon Petroleum Board to pay $5 million USD worth of Sri Lankan rupees in monthly tranches to the state-run Sri Lanka Tea Board (SLTB). SLTB would work with exporters to ship Iran the tea equivalents.

“Tea for oil” was the first time Sri Lanka repaid its foreign debts with an agricultural commodity. The government claimed the “trenches of USD 5 million equivalents” would not violate international sanctions on Iran as tea was categorized as a foodstuff item “on humanitarian grounds.”[1]

In August 2023, the Petroleum Board transferred the first $5 million USD-in-rupees tranche. During those nineteen months, signatories anxiously assessed Iran’s accretion of sanctions on their petroleum networks but also Sri Lanka’s economic-cum-political crisis. In July 2022, civilian protests had forced then-president Gotabhaya Rajapakse to resign and flee the country. Weeks after, Parliament appointed Ranil Wickremesinghe president, a seasoned politician and former Prime Minister. In March 2023, months before the first shipment, Wickremesinghe’s government introduced the Anti-Terrorism Bill (ATA) to expand presidential powers over civil society.

While the state explicitly suppressed citizens’ rights, the tea industry deployed subtle, consensual tactics of repression. In August 2022, plantation trade unions-cum-political party leaders flocked to the side of the president at a lavish tea party to open Parliament. In March 2023, as the government gazetted the ATA, plantation companies held a Best Tea Harvester competition for employees. The winner, a worker named R. Seethayammah, plucked 10.42 kilograms of tea leaves in twenty minutes. Her prize-winning rate, 52.3 kilograms per hour, received “the highest score of 82.6%.” Managers donned her with a green sash and gold-plated tiara, and she took home a 300,000-rupee (about $900 USD) cash prize. That month, the Sri Lanka Tea Board sold 61.5 million kilograms of tea—roughly $260 million USD in sales. In September 2023, the same month SLTB sent Iran its first tea tranche, SLTB auctioned nearly 200 million kilograms, amassing $700 million USD in sales.

The international community lauded Sri Lanka’s replacement of the crisis and debt with political suppression and profit accumulation. In February 2024, Donald Lu, Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs, remarked:

There’s no greater comeback story, than the story of Sri Lanka . . . a year and a half [ago], you will remember a country in crisis . . . mass riots in the street . . . lines for petrol and for food snaking around the corners . . . If you’ve been to Sri Lanka lately, it’s a very different place! The currency is stable. Food and fuel prices are stable. They’ve gotten reassurances on their debt restructuring, and the IMF money is flowing. How did they do that? . . . with a little help from their friends.

Said friends were Sri Lanka’s international lenders like China and the United States—not Vijeyeletchumi and Seethayammah—even though the latters’ blood had stopped the state from bleeding dollars.

2023 marked two hundred years of Hill Country Tamils’ struggle for rights in Sri Lanka. The reckoning carved out spaces to publicly reconstitute the plantation’s “tormented chronology” in the country (Glissant 1999; McKittrick 2021, 183–5). From the Mannar to Matale Walk and Malaiyagam 200 Declaration to the Rooted Exhibition, each node reassembled sites where the state, nationalist movements, and militarization had activated the plantation’s violence. Each also exposed Sri Lanka’s stubborn anchoring to the plantation’s “earthworks” (Gramsci 1971: 238). The substitutions above expose the state’s teeth as they intimately and quietly break the skin of workers who pluck the tea leaves that keep the country’s oil and currencies flowing.

Plantation trenches continue to shelter state tactics of hegemony. Stuart Hall notes how the state wages Gramsci’s “war of position” from the “‘trenches’ and the permanent fortifications of the front” (Gramsci 1971, 243; Hall 2019, 40). In the trenches, like a leech, the state cuts a “vestibular gash” (Weheliye 2014, 44) in the flesh of workers positioned only in its rear lines. Its anticoagulant greed keeps their blood flowing, replacing “rapid fire-power of cannons, machine guns, and rifles” (Gramsci 1971, 234) with workers’ consensual prize-winning, but never on target, plucks.

Workers contest to be the fastest, only to repay the state’s debts in bought-leaf tea. Moist tobacco and slaked lime plaster their wounds and unowned line-rooms, but when chewed together, meld labor ecologies of shame. For, to earn a wage, workers need stimulants to keep plucking in the elements. Plantation unions front foremost as political parties, tethering themselves not to collective action for a living wage, but to majoritarian alliances and their politics of adjacency. Substituting platforms of liberation for high tea with the architects of suppression, such tranches and trenches in Sri Lanka’s markets of authoritarian austerity leave only tobacco plasters and gold-plated tiaras for workers like Vijeyeletchumi and Seethayammah.

In November 2023, two months after the first tea-for-oil tranche, Sri Lanka signed another bilateral agreement—this time with Israel. The agreement authorized the hiring of 10,000 Sri Lankans to replace the nearly 20,000 Palestinians who were banned from working on Israeli farms. Earning remittance dollars in Israel, the migrant workers’ earnings would, in turn, support Sri Lanka’s economy. Aware of Israel’s mass killing of Palestinians in Gaza and ongoing settler sieges in the West Bank but unable to survive in debt trenches at home, one prospective Lankan migrant justified his choice, referencing his country’s own civil war: “we can face anything.”

[1] "Trenches," substituted for its cognate, tranche, is a typographical error in the Plantation Ministry's media release and captures well the substitutive relations between the tea industry and Sri Lankan state.

Glissant, Édouard. 1999. Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays. Translated by J. Michael Dash. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Gramsci Antonio. 1992 (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. Edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International.

Hall, Stuart E. 2019. “Gramsci’s Relevance for the Study of Race and Ethnicity.” In Essential Essays, Volume 2: Identity and Diaspora, edited by David Morley, 21–54. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

McKittrick, Katherine. 2021. Dear Science and Other Stories. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Weheliye, Alexander. 2014. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.