Warship Russia and the End of Profanity

From the Series: Russia’s War in Ukraine, Continued

From the Series: Russia’s War in Ukraine, Continued

My friend Maryna, a Ukrainian Sign Language interpreter, has been posting short videos via Facebook and Telegram since the start of the war. A few days in, she ended her video with a unique “send-off.” Switching from Ukrainian to Russian, she deliberately signed and spoke the words “Русский кoрабль—иди нахуй!” [“Russian (war)ship—go fuck yourself!”].[1] The now-famous catchphrase[2] of Ukrainian resistance to the war originated on the day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as a warship approached the small military outpost on Snake Island in the Sea of Azov. As the story goes, the ship contacted the small contingent of troops on the island, introduced itself, “I am a Russian warship,” and instructed the Ukrainian soldiers to lay down their weapons and surrender. The soldiers’ retort telling the warship where to go quickly became the grand metaphor for Ukrainian resistance and refusal to capitulate in the face of an invading force, a “warship Russia.”

This embracing of profanity woven into slogans is, of course, not new to the Ukrainian context. In 2014, I gathered extensive material on profanity during the Maidan period, including the complex and clever ways people played with “masking” and “unmasking” just enough profanity to communicate anger and disrespect while staying just this side of legal and social conventions that restrict public profanity. Then, in March 2014, after the Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea, the membrane of civility broke in the lightning-fast diffusion of a one-line “folk song” whose only words were “Путин хуйло, лалалалалалалала” [“Putin is a dickhead, lalalalalalalala”]. Soon, a video of 60,000 people singing the song at a soccer match went viral. A few months later, the Ukrainian Minister of Foreign Affairs was fired after being caught on camera using the phrase in conversation with protesters. The capacity of the public sphere to absorb profanity had stretched to its limit; a new government, even one more aligned with the position of Maidan protesters, could not accommodate one of its representatives crossing this profane line, even in a moment of unprofessional but giddy comradery.

When I spoke with Ukrainians about the playful and not-so-playful ways that profanity became an unprecedented part of public discourse during this time, they inevitably identified it as a historical moment when rage broke through: profanity as a violent retort. The EuroMaidan protests, peaceful before sliding into state-sponsored violence, the annexation of Crimea by Putin, the descent into ongoing conflict in Donbas, all represented a steady escalation of tensions, violence, and rage. Unmasked profanity spilling into the public sphere, people assured me, did not represent a fundamental abandonment of civil discourse. It was, in its own way, violence: symbolic, but drawing on the same emotional resources. Like rage, it would pass. Constraints on polite speech, keyed to aspects of gender, class, and status, would return.

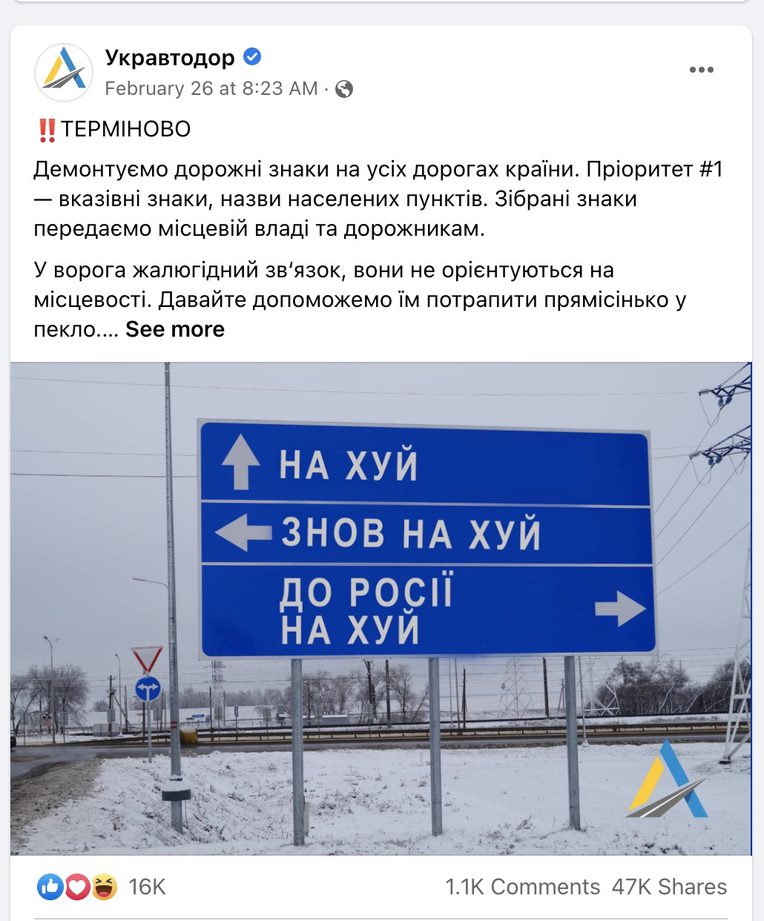

And it seemed for a while it had. Hashtags and asterisks once again covered key letters in “nonnormative vocabulary,” the eight-year war in Donbas outlasted several ceasefires, Ukraine elected a comedian-turned-politician, a pandemic occupied the world. Then, in late February, a full Russian invasion of Ukraine was answered by defiant profanity. And this time, unlike in 2014, the profane catchphrase was embraced even by official media outlets, most famously when the Ukrainian State Agency of Automobile Roads encouraged civilians to remove and alter road signs in order to confuse invading forces. Now we are seeing unmasked profanity not only in the public, but in the state-sanctioned sphere.

Such willingness to accept profanity was deliberate and subject to extensive metacommentary. In the first week of the 2022 war, women, in particular, would post unmasked profanity with a declaration that they should not be judged for doing so, equating this profanity with patriotism. In this state of exception beyond the extreme limits of the norm, people are willing to sit with profanity in new and unexpected ways. It has become a weapon against losing hope: a rallying cry.

The Ukrainian Postal Service sponsored a contest for the design of a stamp commemorating the catchphrase of this war and posted the winning design, a Ukrainian soldier silhouetted against the backdrop of a Russian warship, defiantly holding up a middle finger. Through acts such as this, official sanctioning of profanity offers a social commentary on the position Ukrainians now occupy: they are living in profanity, a place where violence is part of everyday life. This resistance has “filtered out” to other domains, such as in the orthographic demotion of proper nouns by eliminating initial capitalization in words like “russia” and “putin.” As with profanity, these usages also “filter up” and are adopted in diverse locations in the architecture of state power; for example, in a widely circulated video, well-known educator, Ukrainian language textbook author, and “popularizer” of Ukrainian Oleksandr Avramenko underscored the permissibility of spelling “Russia” without capitalization.

In 2014, the taunting lilt of that “folk song” about Putin was just that: a collective snub, a moment of “call the bully out and speak truth to power.” The shouts were meant to hit like a verbal Molotov cocktail being tossed at Putin. In 2022, profanity has been leveraged into something more, into a shield against losing hope. The news from Ukraine gets progressively worse as the catastrophic human toll escalates, but humor, wordplay, and continued belief in the possibilities of Ukrainian sovereignty still come through in creative ways. A recent cartoon entitled “University entrance exam (ZNO) in Ukrainian History 2050” shows a nervous student reading through multiple choice answers to the question, “Where were the famous words ‘russian warship, go to…’ spoken?” In that cartoon is a world of futures in which profanity ends, and Ukraine endures.

[1] This expression is based on a root word хуй (xuj), meaning dick (penis) and the command go to. Maryna, who has remained in Kyiv to provide support to members of the Deaf community, has given permission for me to reference and link to her videos.

[2] The story of the phrase’s origins even has its own Wikipedia entry.