Weaponizing Trafficking: Building a Bureaucratic Wall

From the Series: The Damage Wrought: Immigration Before, Under, and After Trump

From the Series: The Damage Wrought: Immigration Before, Under, and After Trump

The Trump administration systematically dismantled the anti-trafficking legal regime. Not only did his administration create a tangle of administrative red tape to apply for trafficking visas (which protect trafficking survivors who labored under conditions of force, fraud, or coercion), but it also issued new guidance that targeted survivors for deportation if their applications were denied.

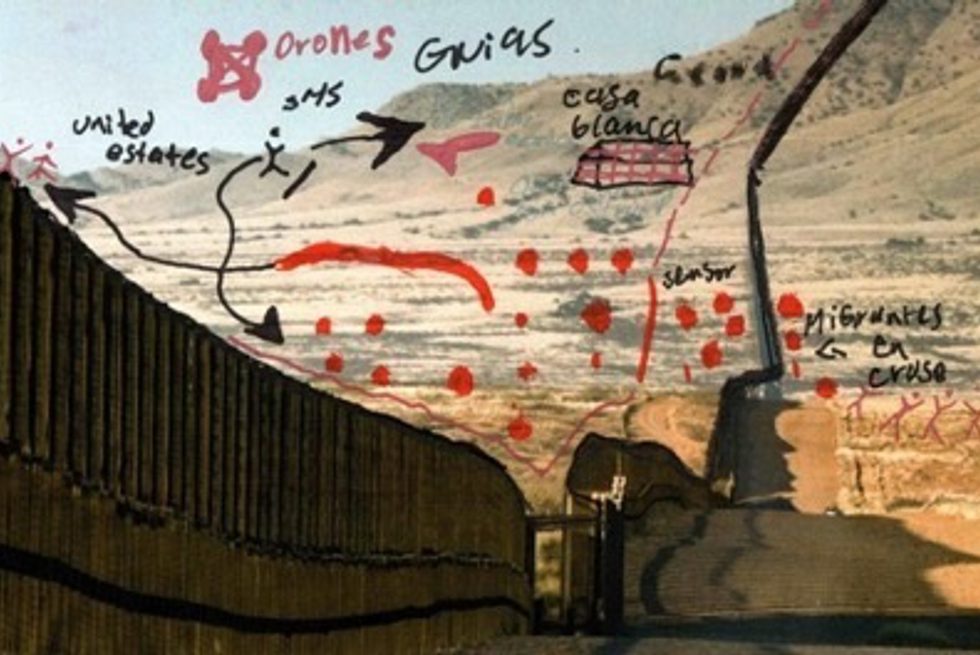

Trump also weaponized trafficking. Pushing the misogynistic narrative that trafficked women and girls were bound and gagged with tape in the back of vehicles crossing the U.S.-Mexican border, he manipulated the issue of trafficking to justify building his fever dream—his “big, beautiful” wall. He became obsessed with tape, referring to it ten times over the course of twenty-two days. The Washington Post wrote about “the eerie specificity” with which Trump talked about the tape: “In Trump’s telling, the adhesive is sometimes blue tape. Other times it is electrical tape or duct tape.” In the Cabinet Room on January 11, 2019, Trump luridly described human trafficking as “grabbing women, in particular—and children, but women—taping them up, wrapping tape around their mouths so they can’t shout or scream, tying up their hands behind their back and even their legs and putting them in a back seat of a car or a van—three, four, five, six, seven at a time.” Trump’s tape talk generates and fortifies his reality to justify his actions (McIntosh 2020).

While President Trump peddled the sensationalized narrative that a border wall would protect women and girls from nefarious actors, behind the scenes his administration threatened to deport trafficking survivors. A memo in November 2018 tied trafficking visa applicants’ fate to other disposable and deportable migrants in the United States. It warned that if a trafficking visa were denied, applicants could be issued a Notice to Appear. Overnight, trafficking survivors went from occupying a protected status rooted in victim-centric legislation (e.g., the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, or TVPA, first passed in 2000), to being criminalized lawbreakers. An attorney in Washington, D.C., described this monumental shift: “it used to be that if you were denied a T visa the paper work would get stuffed into the back of a drawer. But the Trump administration started going after survivors.” The administration also “did whatever it could to not issue T visas,” explained attorneys in New York. “It was death by a thousand paper cuts. Fees that used to be waived weren’t any more. Paperwork was returned asking for more evidence. We had never seen anything like it.” This orchestrated slowdown, a wall of a different sort, left applicants both in suspended animation and exposed to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The administrative wall blocking trafficking survivors from legal protection was part and parcel of myriad machinations to achieve zero migration. “The administration simply made it too dangerous to ask for protection,” explained the D.C.-based trafficking attorney. She and other attorneys advised clients to not even apply for trafficking visas. They did not want to risk putting them on ICE’s radar, especially since ICE and other surveillance workers (local police, Border Patrol, self-deputized proxies, vigilantes) do whatever it takes to surface undocumented migrants, including deploying techniques of concealment, subterfuge, and deception. Beyond high-profile immigration raids, most apprehensions, detentions, and deportations start with surveillance workers lying in wait and lying. In a book I’m currently writing, The Border Is Everywhere: Policing Everyday Life in an Era of Mass Deportation, I argue that undocumented individuals are not living in the shadows, as is so often claimed, but rather, the shadows are where law enforcement stakes them out. At dawn in Jacksonville, Florida, ICE agents wait in unmarked vehicles at gas stations for Latinx workers to emerge from their unmarked construction vans to get their morning coffee. As they return to their vans, ICE agents descend, often without any identifying clothing or insignia. These policing encounters are over in minutes, with few witnesses and little media reporting on how migrants have quietly been disappeared into the vast hidden machinery of the deportation regime.

Through both bureaucratic surveillance and physical stake outs, state agents (and their proxies, like hotel and DMV workers who have given ICE guest lists and lists of driver’s license applicants with “south of the border names”) operate as surveillance workers who stealthily brutalize migrants with impunity. The U.S. immigration regime is a surveillance regime. As with all applications for immigration protection, the T visa process (like applying for DACA) is a surveillance technique (Alvarez Almendariz, this series). Applying for immigration relief means handing over personal data. The risks inherent in this surveillance process intensified during the Trump administration, but began long before his presidency and continue today.

Carving out exceptions for a particular few, such as trafficking survivors, moreover strengthens the carceral logic at the heart of the current immigration system. By constructing categories of “severe” and “less severe” forms of exploitation, for over twenty years the TVPA entrenched binary conceptualizations of worthiness (Brennan 2014). Meanwhile, millions of undocumented migrants labor under conditions of exploitation, just not enough exploitation to meet the TVPA’s bar. Rather than argue over which forms of suffering demand the most immediate redress, we need widespread protections for migrants across labor sectors. Otherwise, undocumented migrants remain vulnerable to widespread, pernicious, and unchecked forms of exploitation—including trafficking.

Trump’s administrative wall will not be easily torn down. The afterlife of his administration’s zero migration policies, including their off-stage attack on trafficking survivors, has wrought long-term damage. But it’s not new. Trafficking survivors, attorneys, social workers, and migrants’ rights organizers argue that targeting trafficking survivors for deportation builds on and compounds long-existing disincentives for undocumented migrants to seek protection. Obama’s deportation spree, Secure Communities Programs that allow local police to work as immigration enforcers, and the detention bed mandate are just some of the ways the U.S. government, regardless of the administration, terrorizes migrant communities. Trafficking into forced labor is preventable. But punitive immigration policies unravel efforts to combat trafficking and locate forced labor survivors. We need policies that offer protections—not handcuffs.

Brennan, Denise. 2014. Life Interrupted: Trafficking into Forced Labor in the United States. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

McIntosh, Janet. 2020. “Introduction: The Trump Era as a Linguistic Emergency.” In Language in the Trump Era: Scandals and Emergencies, edited by Janet McIntosh and Norma Mendoza-Denton, 1–44. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.