This post builds on the research article “Golden Snail Opera: The More-than-Human Performance of Friendly Farming on Taiwan’s Lanyang Plain,” which was published in the November 2016 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Sander Holsgens: “Golden Snail Opera” is visceral, affective, textural. You call it a more-than human performance. This ecological interest opens up to a layered, mysterious audiovisual portrait of the underwater snail. Later, the video presents microscopic images, all of which remain unexplained. I found myself thinking of the film as a response, albeit in a different medium, to Eduardo Kohn’s (2013) How Forests Think. Does that characterization resonate with you and, more generally, how does one work toward an anthropology beyond the human?

Golden Snail Team: What a delightful way to think about this: a Sound + Vision–style response to How Forests Think.

But Kohn isn’t alone. It’s an exciting time for those of us working on more-than-human sociality, because all kinds of ethnographic and theoretical approaches are popping up. One way to think about the dynamics of this confluence is the new sense of permission to cross imagined disciplinary borders. For example, Kohn develops unexpected overlaps between semiotics and biology. In our piece, we open ground on which ethnography can join natural history, on the one hand, and aesthetic practice, on the other. We’re interested in landscapes as sedimentations of more-than-human activities. To watch all kinds of beings making worlds, and the structured consequences of cross-kinds interactions, we need this space where empirical observation stretches to include not only what we’ve thought of as biology, but also ghosts.

Genre and message come together here. Whether through performing, watching, or reading, we ask participants to move their attention back and forth between the film and the script. We have composed a dialogue across these two media. The point is the polyphony—the back-and-forth attention not only to different media but also to different kinds of humans, different living beings, and even different nonliving beings.

We’re glad you noticed the mystery. Anthropologists too often assume that people know exactly what they are doing. Instead, we offer world-making in which every kind of participant, human and nonhuman, has only a partial grasp of what’s going on. Texture and affect emerge from the indeed visceral dilemmas of this situation.

SH: Could you explain why you decided to publish a script that is composed to be read aloud alongside the video piece, rather than including a voice-over? Was this structural decision made to encourage those engaging with the film-text to do so in a performative manner? Is there an affective relationship between the spoken text and video that a voice-over might not have been able to achieve?

GST: People keep asking why we don’t just record a more professional version—or better yet, omit the performance all together. But performance—indeed, amateur performance—is important to this piece. We publish a script to encourage others to perform. The piece is about how different ways of being intersect, and it’s the performance that shows you this coming together and divergence as a process, rather than as a fact. In speaking the parts, even badly, performers show how multispecies living-in-common emerges. It’s the embodied coming to coordination, rather than the completed, perfect mosaic, that matters.

We’re also drawing here on legacies of amateurism that bring us to a promising intersection of natural history and ethnography—and this really matters in this moment of Anthropocenic environmental threats. Natural history and ethnography are both fields that reject the professionalism of the twentieth century’s great utilitarian transformation of scholarship across the natural science/social science divide. We argue that these amateur, holistic, and self-consciously naïve fields can be stretched and revived. By opening up natural history and ethnography through dialogue with one another, we might attend to and defend that multispecies livability threatened by industrial agriculture and other Anthropocene insults.

We are inspired, too, by the informal settings, amateur sensibilities, and queer confusions of identity in Taiwanese opera, as we describe in the note to readers at the beginning.

SH: I’m interested in the ways you blend action-cam material and expansive soundtracks with carefully composed, static long-takes and time-lapses. Formally, “Golden Snail Opera” seems to build upon a diverse range of filmic approaches: sensory ethnography, slow cinema, experimental video art. Could you describe the process of filming it, and expand on how you think these different filmic conventions relate to or perhaps complement each other?

GST: Sensory ethnography and slow cinema are open-ended practices, in which new films continually set new precedents. This has allowed us to work out our own approach. We learned through experiments, such as our snailcam. Joelle and Isabelle built the snailcam out of a battery-operated spy camera and some velcro, though this ultra-light rig still ended up being too heavy for the golden apple snails. The terrestrial snails around the paddy roamed free and grew large, though, and we recruited the help of a giant African snail who was undaunted by the weight. Then we discovered the spycam has a 30-centimeter focus point, so everything before this depth is out of focus. It wasn’t our intention to make the shot blurry, but given that snails are blind except for light and dark, and that they “feel” their way forward through a combination of other senses, de-privileging the visual was actually an essential step in trying to understand another way of being. It may look like experimental video art, but this wasn’t the intention; instead, this was a way to work with the chaos and spontaneity that comes from giving up filmic control and applying this indeterminacy toward a representation of being. Ultimately, we tried to embed our arguments within the very filming and recording, looking for techniques which allow a making-with instead of making-at. This is not just about putting a camera, however small, on top of an animal, seeing how smoothly a snail glides. Rather, it is about pushing the limits of knowing within an audiovisual realm.

SH: Reading the script aloud while the video piece was playing, I noted the literary quality of the writing. There are contextual hints—one might call them suggestions of thick description—but the emphasis is on something more intimate, perhaps even experiential. You write, “Movement: it flows, like drowned souls in the water.” Indeed, you announce a particular kind of phenomenology by writing, “I am the mud; I am the seasons; I am the snail; I am the rice stalk on which they lay their eggs. I do them and I do them in!” Insofar as this is a collaborative project between four scholars, I’m wondering how moving passages like these came about. More generally, what importance do you place on the literary qualities of your work?

GST: Writing is never an ornament; it’s central to making an argument. We aimed to use the rhythms of language, just as we did with the film, to express the situated, sensory engagements of the characters and their interactions with each other. The ghost needs a different voice than the other characters, because it speaks from an unknowable position and without a fixed identity. The ghost’s voice drags, stalls, and stabs; it stretches and collapses time; it breaks the rhythms of both professional and ordinary speech. Juxtaposed with the ghost, the pedant and the farmer also have rhythms. One goal, for example, was to show scholarly prose as strange, that is, pedantic, rather than just business as usual.

Writing this way was challenging: a tribute to distance-defying technology. The team was scattered across three continents, with Tsai and Chevrier in Taiwan, Carbonell in California, and Tsing in Denmark. We managed to find times to meet across all of those time zones and, indeed, we worked in these telemediated face-to-face meetings for many hours. We switched back and forth between film and text, so the text could reflect developments in the film even as the film spoke to the text. It was exhilarating! We had to learn each others’ senses of humor as well as scholarly commitments. When a phrase or film section rang true to one collaborator but not others, we negotiated. And, of course, we all had fun with the ghost.

SH: In the endnotes, you refer to a particular strand of visual anthropology, which you describe as based on “image-sound.” You cite Lucien Taylor’s (1996) “Iconophobia,” and you rethink Anna Grimshaw’s (1997) and David MacDougall’s (1997) interest in a kind of filmmaking that allows for ambiguity. How, more specifically, do you position your work within this theoretical and methodological framework?

GST: Filmmaking stimulates thinking; it’s not just entertainment. At the beginning of our film, we plunge people into an unfamiliar experience through a camera mounted on a snail. By making people watching five minutes of uninterrupted snail footage, the film allows viewers to slow down to the rhythms of the snail. We cannot see very well, we cannot hear very well, we don’t know what this is, and we have to allow it to wash over us. Just when we are finally getting used to this strange new world, we are then confronted with an image we finally recognize: a puddle of water with a reflection of a rice plant. Then we’re plunged into water, and we see our first glimpse of the creature we were just getting to know: the golden apple snail. This is the heart of sensory ethnography, the chance to move beyond what’s possible on the page. Our film asks for an active engagement. Viewers must work to figure out where the image, and the sounds, take us.

Film can draw us into an experience that may be indeterminate. The film we made does something that writing can’t: it shows us things that we don’t understand. Our theoretical framework builds upon this by stressing relational curiosity and the ecological consequences of living in common, perhaps creating a new methodology for ethnographic documentary filmmaking, one that’s based on a multispecies, multilinear approach: making-with, researching, and learning about the world through film.

SH: Lastly, it’s fantastic to hear you’re also presenting “Golden Snail Opera” as a live performance. Could you tell me more about this? How and in what capacity will the piece be performed?

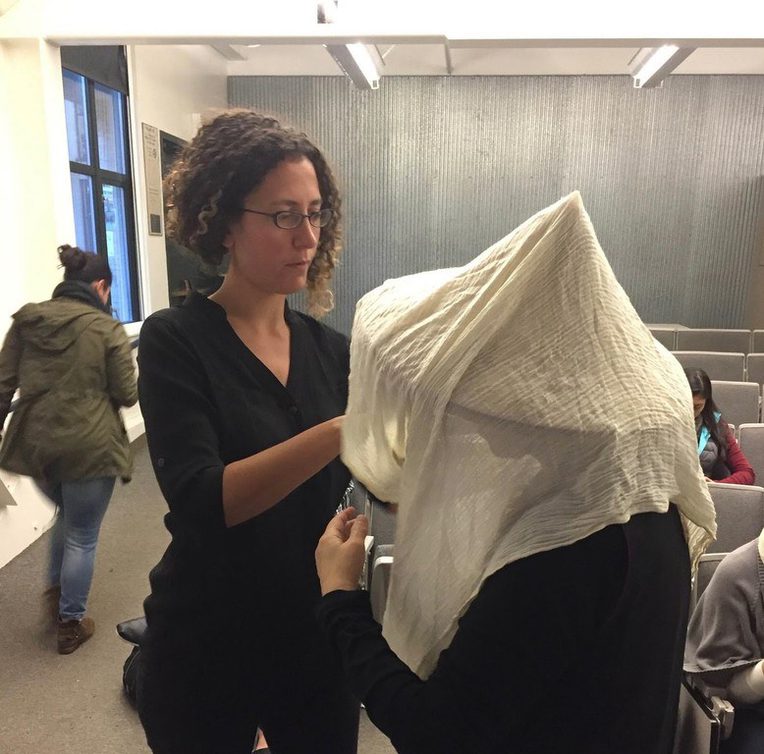

GST: In various combinations and versions, team members have performed the opera in several settings: at a rural inn as part of a student-and-faculty field trip; at a conference on development; in a classroom. In the photo you’ve reproduced above, which was taken before a performance, Isabelle (Pedant) adjusts a costume for Anna (Wanderer). We’re hoping that others will be inspired to perform, too. We are particularly excited about classes in which students read the roles; we think the piece would be a great teaching tool. Perhaps there are other settings, too, in which it will be fun to perform: an anthropology or STS party. Certainly, we are planning to continue to perform it. Yen-Ling and Joelle are planning a Chinese version to be shared with the friendly farming community at the annual village forum. Both audiences and performers continue to inspire us!