Wildness

From the Series: Lexicon for an Anthropocene Yet Unseen

From the Series: Lexicon for an Anthropocene Yet Unseen

Two decades before the idea of the Anthropocene gained global traction, the environmental historian William Cronon (1996) made a call to think not of wilderness, but wildness. In a decade of scholarship that largely focused on the adverse social impacts of conservation, Cronon took a step beyond critique. Quoting Henry David Thoreau, who wrote that “In Wildness is the preservation of the World,” Cronon (1996, 86–89) suggested that wildness “can be found anywhere,” that it is “within and around” each of us. It can be found in a backyard garden; it can be found in the city; it can be found in a front lawn. Wildness need not reject the human.

In the Anthropocene, the wild meets domestic and the native and invasive blend. This is nothing new, except that now we seem to accept intermingling and disturbance as inevitable facts. Consequently, sociocultural anthropology—a field that grapples with the complexity of being—is well suited for research in the Anthropocene. Intermingling occurs in time as well as space. When traced back in time, crops and domestic animals have wild ancestors. Endangered species are kept in zoos and breeding grounds to ensure future propagation. Given enough time and the right kind of space, the domestic becomes feral and approaches wild again. For some people, wildness evokes a sense of loss for what once was; for others it is simultaneously an axiom of hope for what will be: restoration, renewal, rewilding.

Rewilding is often conjured as an antidote to the Anthropocene’s human dominance of geographic space. Yet the irony is that rewilding projects are human-driven (see Marris 2011; Lorimer and Driessen 2014). In one approach to rewilding, nonnative species substitute for the roles once held by extinct corollaries. For instance, Paul Robbins and Sarah Moore (2013, 12) describe how an endangered ebony species is being restored through “island rewilding” in the Indian Ocean. Scientists (Griffiths et al. 2011) have introduced a nonnative giant tortoise to disperse the endemic ebony’s seeds, a role once filled by a now-extinct native tortoise. The ebony trees are nurtured by a human-mediated relationship with another wild—but not native—species. Different forms of wildness meet.

Conceptually, wildness can transgress borders between human and not human, nature and culture. Walking through the Massachusetts landscape more than 150 years ago, Thoreau ([1854] 1995, 233) foreshadowed the contemporary ethos of rewilding. In Walden, he reflected on an edible groundnut that had been used as food by Native Americans: “In these days of fatted cattle and waving grain-fields this humble root . . . is quite forgotten.” Yet if humans were to step aside, Thoreau envisioned a different future:

Let wild Nature reign here once more, and the tender and luxurious English grains will probably disappear before a myriad of foes . . . but the now almost exterminated ground- nut will perhaps revive and flourish in spite of frosts and wildness.

In this vision the domesticated gives way to the wild through human absence, but Thoreau also understood wildness as a human trait. “Life consists with Wildness,” he wrote in the essay “Walking.” “The most alive is the wildest.” In this sense, wildness transcends distinctions between humans and nature to emphasize life. Wildness does not entail an absence of humanity but rather vivaciousness: a quality that can apply to people as well as plants, wheat fields as well as prairies, dogs as well as wolves.

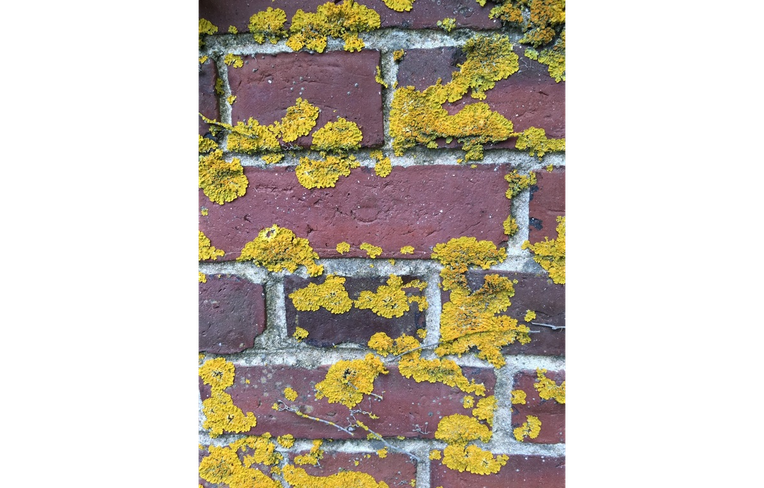

Through life, wildness encompasses the domestic and the tame, as well as that which is beyond human control. Building on Thoreau, Cronon (1996, 69, 89) further demonstrates why the concept of wildness is so apt for the Anthropocene. Unlike societal conceptions of wilderness, wildness is not dependent on the fiction of untouched spaces, devoid of human history. Yet the idea that wildness can crop up anywhere, even in the most ostensibly tame places, upsets human efforts to order and predict the world. For instance, as wildfires burn larger and longer, people evacuate cities not knowing to what they will return—this, too, is wildness. Wildness in the Anthropocene is exuberant, transgressive, vivid; it blends categories.

While wildness can flourish in the most human of places, for some conservationists the wild remains a clarion call to push back against anthropogenic change. Yet nonhuman species also push back. In nature’s agency and its ability to adapt and grow, wildness transcends categories (such as native and nonnative) that we ascribe to species. This agency is expressed in Ashley Carse’s (2014, 208) work on the Panama Canal. If sustained efforts to manage invasive water hyacinth were stopped, he notes, “the canal would be impassible in three to five years.” Left alone, this aquatic weed would clog a crucial artery of global trade. Exuberant, growing unbidden, the water hyacinth is emblematic of wildness in our current era.

If the Anthropocene will have a lexicon, it should be a wild one. It should be a set of terms that pushes our thinking beyond simplified ideas of human dominion. We should be unsettled just the right amount, in this so-called human era. We should not lose sight of ourselves as actors who create new forms of wildness even as we erase others. By carefully situating ourselves within not only social but also ecological webs of interconnection, we can guard against the grandiosity and anthropocentrism of the Anthropocene. This epoch named for ourselves—is it a cautionary term, or, as Cymene Howe and Anand Pandian suggest, “the ultimate act of . . . self-aggrandizement”? Do we laud our capacity for lasting change at the same time as we deplore and fear it?

Who does not long for a little bit of wildness?

Carse, Ashley. 2014. Beyond the Big Ditch: Politics, Ecology, and Infrastructure at the Panama Canal. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Cronon, William. 1996. “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” In Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, edited by William Cronon, 69–90. New York: W.W. Norton.

Griffiths, Christine J., Dennis M. Hansen, Carl G. Jones, Nicolas Zuël, and Stephen Harris. 2011. “Resurrecting Extinct Interactions with Extant Substitutes.” Current Biology 21, no. 9: 762–65.

Lorimer, Jamie, and Clemens Driessen. 2014. “Wild Experiments at the Oostvaardersplassen: Rethinking Environmentalism in the Anthropocene.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39, no. 2: 169–81.

Marris, Emma. 2011. Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World. New York: Bloomsbury USA.

Robbins, Paul, and Sarah A. Moore. 2013. “Ecological Anxiety Disorder: Diagnosing the Politics of the Anthropocene.” Cultural Geographies 20, no. 1: 3–19.

Thoreau, Henry David. 1995. Walden: An Annotated Edition. Edited by Walter Harding. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Originally published in 1854.