Young Mexican Border Crossers’ Grammar of Resistance

From the Series: The Damage Wrought: Immigration Before, Under, and After Trump

From the Series: The Damage Wrought: Immigration Before, Under, and After Trump

As the Tigres del Norte song says, If they catch me today, I'll be back tomorrow. And if they catch me again, I will be back the day after tomorrow. Wherever you go, don’t be scared, because you’ll die where you’re meant to.

—David, a seventeen-year-old Mexican border crosser

Among the most impacted by President Trump’s zero tolerance immigration policies have been young border crossers, often referred to as “unaccompanied minors.” The label unaccompanied minors conjures images of passivity, such as photos of Latinx children wrapped in Kevlar blankets and crammed into cage-like holding facilities. The term also erases young people’s ethnic and national diversity, as well as their active strategies and networks of accompaniment, solidarity, and care, evidenced in David’s opening words. Young border crossers are guided by stories of crossing in popular music, as well as by advice from fellow young crossers. Young people from South America, Central America, and Mexico have a long history of crossing the border alone or in caravans, often to escape life-threatening conditions related to forced gang participation in their home countries, conditions that have been perpetuated throughout Latin America for decades by the U.S. government. Although the presence of young crossers is not new, their dehumanization and punishment intensified under the Trump administration. This included fast-track deportation schemes and policies that forcibly separated children from parents, resulting in children going through their deportation hearings alone.

The intersection of policy and nationality complicate the experiences of young Mexican border crossers in particular, who rarely qualify for asylum. Young Mexicans are usually immediately sent back across the border by immigration authorities. During the COVID-19 pandemic the U.S.-Mexico land border was officially closed and Amnesty International reported that while unaccompanied children were not supposed to be removed from the United States, “Mexican children continue[d] to be swiftly returned to Mexico under another law, and remain almost entirely without access to asylum procedures.” In response, one of the primary strategies of resistance employed by young people was to remain positive and patient as they attempted multiple crossings. As seventeen-year-old Javier reflected, “You must smile despite everything. I just want to feel the American dream. There is only one life, attempts [at border crossing]—a thousand.”

This narrative comes from a reflective writing activity led by Glockner in 2019 with young Mexican border crossers who had been deported by the U.S. Border Patrol to Mexico. Young border crossers’ communal and individual encounters with authorities on both sides of the border provide insights about their perceived fragility as well as the disposability of their Brown, “undocumented” and “illegalized” bodies. Many were aware of the racialized conditions that they would face when crossing and offered advice to others regarding socially constructed dangers along the way. Sixteen-year-old Marcelino explained, “I can only tell [my Mexican peers] to be very careful when attempting to cross, because they really risk their lives. They suffer from cold, hunger, heat, thirst. Freedom! No to racism. No more deaths.”

Young border crossers’ narratives show a subaltern “grammar of resistance” as they employ a series of devices that confront and defy racist, xenophobic, and criminalizing discourses. They replace these discourses with narratives of self-worth in which they claim their right to migrate to lead a life of “honesty and hard work.” As seventeen-year-old Renaldo explained, “I came to help my family. I have suffered a lot. I’ve tried it five times, but I still don’t give up. I have been kidnapped once, but I don’t give up, I know I’m strong. My story is true. Have courage, life goes on!” Renaldo and other young crossers’ words challenge hegemonic narratives about which lives are valuable and what reasons are (in)valid to cross to the “other side.”

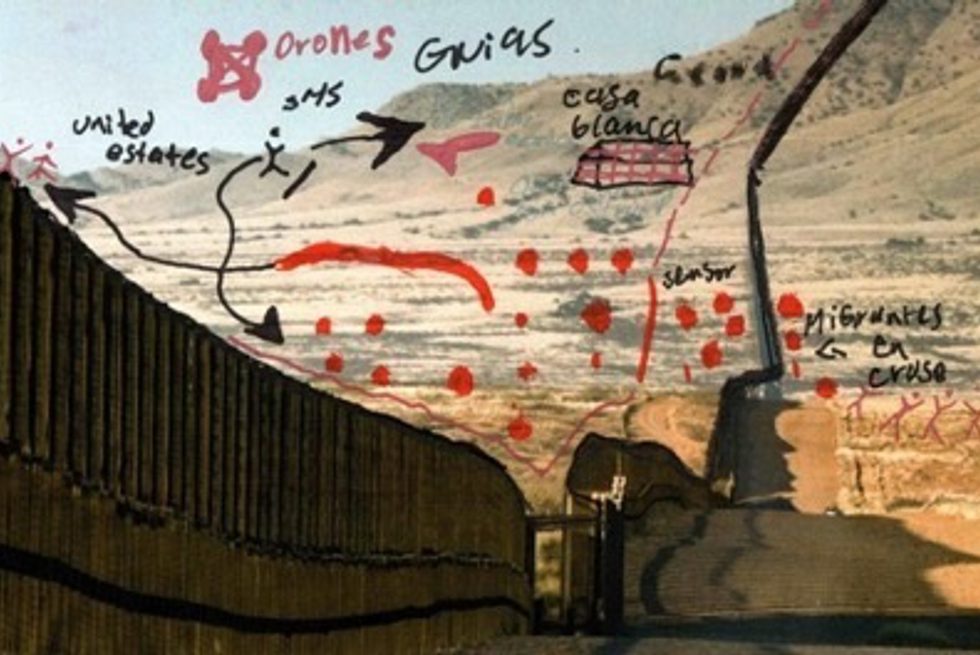

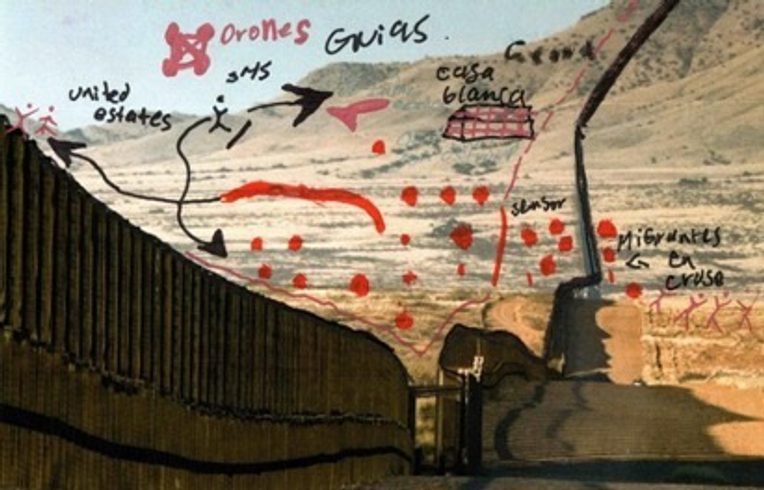

This grammar of resistance also includes words that describe the range of responsibilities young people take on to help keep one another safe. Some of its terms include: coyotito (immigrant guide), brincador (“wall jumper” who helps people climb the border wall), halconcito (lookout), and agüero/aguador (water carrier). The illustrated photos below created by participants in Glockner’s writing workshop capture how young Mexican border crossers creatively build a network of young people to mitigate the dangers they may encounter.

Young border crossers work together to stay safe and in control of their passage to the United States. These acts of care, strategy, and solidarity are also acts of emancipation. They dare to defy assumptions about them, and instead narrate their own stories. Young Mexican border crossers offer just one example of young people’s grammars of resistance as children on the move throughout the Americas.