How Oil Palm Plantations Deforested the Tesso Nilo Forests

From the Series: Firestorm: Critical Approaches to Forest Death and Life

From the Series: Firestorm: Critical Approaches to Forest Death and Life

Environmental issues such as deforestation in late modern society must be understood in relation to society and political economy. In the Indonesian province of Riau, the Tesso Nilo forests were once the largest contiguous forest in Sumatra. After gaining international recognition for holding some of the world’s most diverse plant life and providing priority Sumatran tiger and elephant habitats, the Indonesian government worked with the World Wildlife Fund to formalize the creation of the Tesso Nilo National Park in 2002.

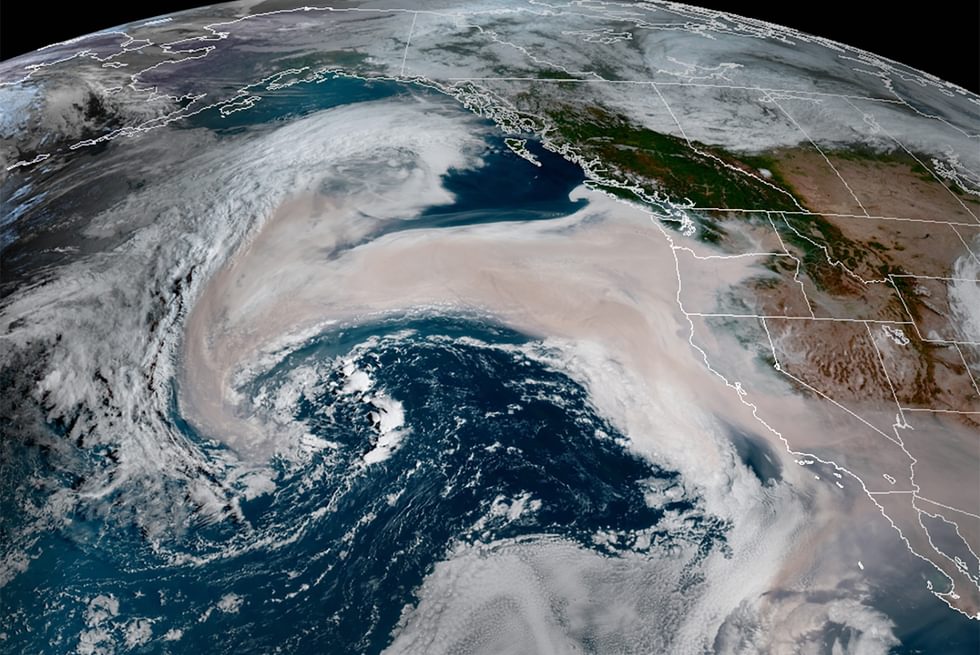

Roughly three-quarters of the forests in the national park have been cut down in the last decade, with nearly all it replaced by oil palm plantations (Kartodihardjo and Muhammad 2019, 254). In a complex interaction between industrial logging, large-scale oil palm plantation companies, and smallholder family farmers, the forests fell. Forest fires due to land clearing for new plantations occurred in the Tesso Nilo area. Satellite imagery shows quite a large area burned in 2012–2015 both within and outside companies’ concessions. Some of the forests burned in the Tesso Nilo National Park area. These fires clearly also contributed to deforestation in this area.

The forest changes are related to government agriculture policy. Both the central and local governments encouraged and facilitated the development of oil palm plantations in Riau in the 1990s. At the early stage, they promoted the development of large-scale oil palm plantations by inviting big investors (both domestic and foreign) to come to Riau, eventually remaking Riau with the largest oil palm plantation area of any province in the country (2,210,000 hectares in 2017, with 1,530,000 of them managed by smallholders [BPS 2018]). Agribusiness built oil palm mills to press the oil palm fruits into oil, but it was these mills that opened an opportunity for independent smallholders to establish their small-sale plantations and sell the oil palm fruits to the company mills. Forty-six of them operate near Tesso Nilo Landscape and Tesso Nilo National Park.

It is important to remember the industrial oil palm plantations came after the logging of the forests. Then came nearly two thousand households of smallholder cultivators, mainly migrants from nearby communities and further afield from North Sumatra. The logging operations in the 1980s cleared many canopy trees, and even more importantly built a series of access roads, called Jalan Poros, deep inside the forests connecting Tesso Nilo to the Trans-Sumatra Highway.

Smallholders followed the road, transforming the deforested hills into agricultural land. Because of high land prices in their homeland, they decided to move to Tesso Nilo where they heard from their relatives and friends that cheap land was available to buy. They purchased two to three and even more hectares of land for around four million rupiah per hectare. It seemed that to them that Tesso Nilo was their future: They brought their family members with them to live in Tesso Nilo. The cultivators and the inhabitants of new settlements believed they had rights to the land they cultivated and lived on. For local people indigenous to the area, the land is their kinship group’s (suku or perbatinan) customary land to which they have utilization rights granted by their kinship group leaders: Batin, Datuak, or Ninik Mamak.

The migrants bought land mostly from Indigenous kinship group leaders, whom the migrants thought to be the owners of the land. As evidence of ownership to the land the migrants hold letters of land purchase from Batin, Datuak, or Ninik Mamak that were approved by village officials and Surat Keterangan Tanah (Letter of Land Status, SKT) issued by village and sub-district officials. A group of cultivators in Palalawan District even obtained land certificates for 1,080 hectares land within the national park from a district Land Agency in 1998/1999. The local government issued Kartu Tanda Penduduk (identity cards, KTP) for the migrants, and the district government issued a regulation to make their settlements inside the national park new villages of the district. During the 2002 election for the Palalawan district head, candidates sought political support from migrants who lived and cultivated land in the national park. All of this created a perception that migrants’ control of the land was legal.

Even while the government was formalizing the new migrants’ land control and settlements, officials in the National Ministry of Forestry, the government of Riau Province, and the government of Palalawan District labeled the migrants illegal encroachers. These officials justified their criminalization of these smallholders with state laws on forest and land, including the Ministry of Forestry’s Regulation that established Tesso Nilo National Park. Other provincial and district officials viewed the cultivation of forest areas and the establishment of new settlements in the national park as tolerable acts because they had been occurring for a long time without meaningful prevention from governments. Local indigenous people in the area, in particular adat leaders, considered their sale of forest areas to be acts of utilization of land they held rights based on living in the region, the existence of customary laws, and their previous, well-documented land transaction histories.

The trajectory of deforestation in Tesso Nilo reveals the complexity of causes of deforestation. The establishment of roads penetrating Tesso Nilo enabled people to convert forest areas into smallholdings of oil palm monocultures. Local elites sanctioned the sale of customary forest lands, providing a second pathway to forest destruction. Government agroeconomic policies and official’s endorsement of deforestation provided still more ways for people to deforest Tesso Nilo National Park.

BPS. 2018. Statistik

Kelapa Sawit Indonesia 2018. Jakarta: BPS

Kartodihardjo, Hariadi, and Chalid Muhammad. 2019. “Mengatasi Persoalan Institusional Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Alam (PSDA): Pembelajaran dari Kasus Revitalisasi Ekosistem Tesso Nilo (RETN) di Provinsi Riau.” Jurnal Hukum Lingkungan Indonesia 5, no. 2: 253–70.